As I conclude this series of pieces about the work of Ken Loach, I also conclude (obviously) the binge of his work that I’ve been conducting over the past few months. Loach’s work is indeed worth a deep dive, as he has matured as an artist since his days as a troublemaking TV director, blending documentary elements into fictional narratives that were seen, as with <i>Cathy Come Home</i> (1966), by a quarter of everyone in Britain.

In this piece, I’ll be talking about Loach’s work since 2000. Before I do that, however, I will cover two 20th-century items I found online after I wrote the last blog entry.

The first item is the rarest, since it doesn’t even carry Loach’s name but was made by him. (His crew, including cinematographer Chris Menges, do have their names on it.) It’s a short b&w film commissioned in 1971 by the Youth Employment Service called “Talk About Work.” It shows young workers in Liverpool discussing their jobs, with none of them seeming that enthused about their work.

In a quote in the Anthony Hayward book about Loach (<I>Which Side Are You On?</i>, 2004), the filmmaker says the film was “squashed” after it was made and submitted. This is no surprise, as Loach includes a few of his subjects openly saying they are thoroughly bored by their jobs. Others simply note they’re doing it for the money.

The thing that strikes current viewers is that 1971 in Liverpool seems like it could be 1966 or even earlier, as one of the young women working has a framed picture of Elvis on her desk and the song playing at a local dance seen in the first sequence is “The Locomotion” (from 1962).

A younger worker at a car factory declares that his tedious job “dulls the faculties.” (“It slows you up quite considerably — you know, mentally-like.”) A girl sewing in a factory setting discusses her alienation from her job. Finally two older men speak to a group of young people about work and one openly says that hippies have the right idea, as they are “a slave to nobody.”

On the whole, the film was clearly intended as a promotional piece but ends up playing like (surprise!) a kitchen sink drama, except not as engaging or passionate. (I have no idea why the sound disappears at two points in the film; perhaps the things said by the workers just got too despairing?)

“Time To Go” is a short film Loach made for the BBC show “Split Screen” in 1989. It is a short but potent argument that British forces should leave Northern Ireland. Constructed in a conventional documentary style, the film succeeds in making its argument through interviews with Catholic citizens of Northern Ireland and formal advocates for the case (which was dubbed the “Troops Out” movement at the time).

Most stirring of all is an interview with a Catholic woman blinded in 1971 by a rubber bullet shot by a British paratrooper for no reason. Loach cuts from the interview to actual footage of the woman being led away from her house after the shooting. It’s a deeply disturbing moment and makes the troops-out case very eloquently.

It is noted in the Hayward book about Loach that “Split Screen” showed “Time To Go” with a counter-argument made by a Belfast-born playwright who defended the British presence in Northern Ireland.

*****

Back to the turn of this century: Here it is important to remember that the Nineties found Loach making a major “comeback” to theatrical features and forging important relationships with his fellow collaborators. The resulting films made him perhaps Britain’s most noted “arthouse filmmaker” (a phrase I’m sure he’s not fond of, since he wants to reach working class viewers most of all) and continued to show how one can make a fiction feature and spotlight the political aspects of the tale.

As I noted in my last entry on Loach, despite all the common themes found in his work, all the emblematic items he’s included in most of his work (from passionate discussions between groups of people with different opinions to his good-luck charm of having a three-legged dog wander through each film at some point), and the visuals and editing methods that he’s used throughout his work, the biggest constant is the depiction of a working class group with a spotlight shone on how they got into the situation they’re in.

One further note on the foreign interest in Loach’s work. In his book Ken Loach: The Politics of Film and Television [BFI Palgrave Macmillan, 2011], John Hill discusses the many countries that wound up becoming part of Loach’s support-network of production entities.

|

| Shooting I, Daniel Blake. |

“… Loach has been able to access, indirectly, other sources of public funding… through a strategy of European co-production and co-financing…. However, it was Land and Freedom[(1995], the film that followed the short run of films fully funded by Channel 4, that really set the pattern for subsequent funding by securing 40 percent of the budget from production companies in Germany (Road Movies) and Spain (Messidor Films)… and a further 10 percent from the European funding body, Eurimages. Since then virtually all of Loach’s films have been European co-productions that have depended for funding upon a range of production partners, distributors, television companies and public bodies across Europe.” [p. 165]

Hill then goes to note that Sweet Sixteen (2002) was a “German-Spanish-co-production with additional funding coming from distributors in France, Italy Belgium and Holland. The Wind That Shakes the Barley [2006] was a five-way co-production involving partners in Ireland, Italy, Germany and Spain, and relying upon over twenty different financial sources. Loach has subsequently argued that one of the benefits of multiple funders is that ‘nobody has you by the throat’ and that you can therefore make ‘your own film.’ ” [p. 166]

When asked about why his films are popular in other countries when they are most often intrinsically British, Loach answered that people “‘have much more in common with people in the same position in other countries than they do with those at the top of their own society’ and that he would therefore ‘encourage people to see their loyalties horizontally across national boundaries.’ ” [p. 173]

With that said, I turn to Loach’s filmography from the last 25 years.

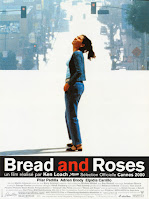

Bread and Roses (2000) is Loach’s only film made in the U.S. It’s not a major studio movie, though, as it was financed by the usual group of production entities from the U.K. and Europe that began funding Loach’s films from the mid-Nineties on.

I spoke of the “tonal changes” that occur in Loach’s films in my last piece, and those are definitely present here. What is most interesting about the last three decades of Loach’s theatrical work is that he has exclusively (with one exception) had one screenwriter, Paul Laverty. Laverty’s initial script, for Carla’s Song (1996), had its moments but it was remarkably uneven.

As the years have gone by, Laverty’s work has gotten tighter, to the point where he wound up writing “Ken Loach films” (meaning scripts that contained elements found in Loach’s TV work and his early Nineties hits like Riff-Raff and Raining Stones) and his versatility grew, so that each new film tackled a different situation from the preceding one. While there are indeed through lines in the films of Loach and the scripts of Laverty, there also are enough differences between them to make them compelling.

Which brings us back to Bread and Roses. The film is based on the very real situation of immigrants who were working in high-rise commercial buildings in Los Angeles whose cause was taken up by an advocacy group, “Justice for Janitors,” and who fought to unionize. The film maintains a mix of deadly serious scenes, punctuated by some lighter comic moments.

The beginning shows how one young Mexican woman (Pilar Padilla) is preyed upon by a “coyote” who brings her to L.A. and tries to rape her. She escapes quite handily (sometimes something in a Loach film does seem like it would happen in a Hollywood movie) and later becomes involved with a union organizer, played by a pre-Pianist Adrien Brody.

The struggles these immigrants face are depicted throughout the film, with an occasional moment of “victory” for the workers, as when Brody’s character arranges for the cleaners in one building to humiliate the owners of the building by infiltrating a ritzy party they’re giving, where Brody gives a speech about how they are screwed by their employers. The scene is a very odd one in the Loach canon, as it features “guest stars” — among the partygoers one can easily see Tim Roth (an avowed Loach fan) and Ron Perlman, and other actors (Chris Penn, Robin Tunney, Benicio Del Toro, Stephanie Zimbalist) are present as well, according to the end credits.

From that last bit one can tell that Bread and Roses is quite an unusual Loach film, but the hallmarks are all there, including the excellent blend of non-professional and professional actors. Loach also continued his casting of standup comedians in supporting roles (because he knows they are very good with ad-libbing dialogue and can inhabit a character). Here George Lopez gives a very good straight performance as the evil overseer who we know is an evil guy (he fires people on a whim) but we later learn he’s more evil than we thought (he demands the female workers sleep with him to get their jobs). Standup Blake Clark also appears as one of the building owners.

Another element that is a constant in Loach’s cinema — passionate discussions about political matters argued by everyday working-class characters — is present here. Laverty also supplies some indelible lines, as when one character declares to our heroine that the bosses like the uniforms the cleaning people are forced to wear because “they make us invisible.”

And an element appears in the dialogue that must always be saluted because it is one of the most reprehensible things about America: the fact that we don’t have universal healthcare and people must go broke to survive if they’re not insured. Our heroine notes to Brody at one point, in reference to the fact that her sister must work extra hard because her husband has diabetes and can’t afford treatment, that her brother-in-law has “no medical coverage, like 40 million other people in this fucking country, the richest in the world!” This is always a welcome inclusion in a movie script.

The Navigators (2001) is a film that was produced to be shown on British television and released theatrically in other countries (a method that has done very well by Loach over the years, giving his films a sizable audience in his home country, a place that began recognizing his brilliance in large part after he was feted abroad).

The script, the only non-Laverty screenplay that Loach has filmed in the last three decades, was written by real-life railroad worker Rob Dawber. What he produced was a realistic (but fictionalized) account of rail workers seeing their jobs disappear from under them as the railways were privatized in the mid-Nineties. The result is a perfect “small movie” — which is more valuable than a dozen blockbusters.

Given Dawber’s background, it’s no surprise that the film focuses primarily on the emotions felt by the rail workers who lost their seniority and staff privileges and had to become freelancers after decades on the job. We see them interact with their families, but mostly we see them interact with each other, and once again a Loach film takes us into the “break room” where workers air their grievances, their fears, and their anger at their employers.

There are no tonal changes here, as the film is about a specific problem — how to stay employed when the industry you work in is being destroyed by money-hungry corporate heads (who would rather see their new company die out if it doesn’t immediately turn a profit). As in Riff-Raff, and was clearly the case in Dawber’s actual experiences, the lack of safety measures becomes a major issue with the workers and sets up a haunting decision that a group of the protagonists have to make at the very end. It’s a perfectly “small” conclusion for a perfectly “small” film.

Sweet Sixteen (2002) is more evidence that the team of Loach and Laverty truly hit their stride in the 2000s. The film could be seen as a more brutal version of the scenario of Loach’s teleplay “The Coming Out Party.” There a little boy leaves his caregiving (and crooked) grandparents to search for his mother when he finds she is in prison. In Sixteen Liam (Martin Compston). a teen who is raised in an equally corrupt (but not cartoonishly so) family, craves the love of his mother, who is in prison, and wants to give her a perfect life once she comes out.

The film thus sketches some likable characters doing crooked things in a very crooked milieu; it was shot and takes place in the Inverclyde cities of Scotland (which are near the Clyde River). Liam hates his mother’s lover for causing her to end up in prison — in an early, brutal scene, the mother’s lover and the boy’s grandfather beat him for refusing to pass drugs to his mother in prison.

A beginning like that makes the film sound incredibly grim — it does have scenes that are very violent and extremely sad but, however criminal the lead is, we know he is doing all this drug dealing and other criminal activity because of his love for his mother and his desire for her to have a nice place to live.

One of the film’s strongest subplots seems like a Scottish riff on Mean Streets, as Liam keeps covering for his fuck-up friend Pinball, who angers a mob leader over and over again and seems suicidal in his crooked activity. It also should be noted that, throughout the picture, one does get the impression that Liam can’t escape from his milieu and is in fact digging himself deeper into it, but the little moments of happiness he experiences with his sister and his friends are the “redemption” and the things that the viewer can cling to, even after the brutality and sadness of the next-to-last scene.

Two of the most memorable lines in the film relate to the self-destruction that is part of the milieu Liam inhabits. In one scene, he needs to find Pinball and so goes to project apartments to find him. His almost-bizarre question snapped at a local woman walking her baby, “Are there any junkies’ flats up here?” quickly gets an affirmative response and he quickly moves on to find said apartment.

Also, his sister notes that the saddest thing she ever had to witness in reference to him was the time he defended his mother’s reputation by fighting some bullies and being beaten severely. The sister sums up what made her so sad about the event, saying that it wasn’t so much him seeking to clear their mother’s name, but “You fought them because you didn’t care what happened to you.”

11'09"01 September 11 (segment "United Kingdom") (2002) is an unconventional anthology that includes several contributions on the topic of Sept 11 by foreign directors (and one American, Sean Penn). The film had a short theatrical engagement in art houses but was not beloved in the U.S. because its various short films spoke very compassionately about 9/11 but also offered context for the event. And if there’s one thing American’s don’t like, it’s context.

Loach’s piece was nothing but context, as it revolved around the words of a Chilean man (Vladimir Vega, the costar of Ladybird Ladybird), who lived through the Chilean overthrow of 1973, which also occurred on Sept 11 and was funded and championed by the U.S. under the supervision of that old warmonger himself, Henry Kissinger.

The film is a tight little piece, in which we begin to understand that old concept of history “rhyming” rather than repeating. Vega recounts the horror of that day in Chile as pictures and footage from The Battle of Chile by Patricio Guzmán are shown.

Vega is seen writing a letter to Americans, decrying what happened at the World Trade Center and recounting his personal memories of the overthrow of Salvador Allende’s government by a military led by Augusto Pinochet under the financial umbrella of the U.S. His haunting final line addresses “mothers, fathers and loved ones of those who died in New York”: “Soon it will be the 29th anniversary of our Tuesday, 11th of September, and the first anniversary of yours. We will remember you. I hope you will remember us.”

Ae Fond Kiss... (2004) is the Loach version of a rom-com, making it the most “normal” entry in his filmography. Returning to Glasgow again, the storyline (by Laverty) concerns an aspiring nightclub owner of Pakistani heritage falling in love with an Irish music teacher.

Complications arise when the man reveals that his parents have arranged a marriage for him with his cousin, whom he doesn’t know. The music teacher has her problems when the priest adviser for the Catholic school she works for demands that she stop living with her boyfriend, because he is a Muslim.

The film does offer up a different kind of working-class milieu, as the Pakistani family own a local deli and our heroine shows her students unconventional things like photos of lynchings in the American South while playing Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” The biggest question, though, is whether the man will step away from the arranged marriage, which is hardly earth-shaking, compared to the dilemmas faced by other lead characters in Loach films.

Two things are of interest here: This is the one time that Loach included sex scenes (non-explicit, of course); there were sequences in other films where it was clear the characters were going to have sex or had had it, but here we do see the activity itself simulated at two different points.

The other notable thing here is that Laverty and Loach step into Fassbinder territory in the second half of the film, when the two lovers are no longer as concerned by the outside world and each needs to conquer their own feelings of hesitation about their partner. (This was the theme of RWF’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.)

Tickets (2005) is an anthology feature that contains segments by Loach, Ermanno Olmi, and Abbas Kiarostami, all set on the same train. Loach’s segment involves young Scottish football fans heading to London to see a game. One of the teens believes that his ticket for the train has been stolen by a little Albanian boy he and his friends had been talking to.

The piece is the last of the three stories contained in the film. While it has a few serious moments, it’s mostly a breezy piece of light entertainment.

The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) was the first film by Loach to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It is set in Ireland in 1920 and focuses on two brothers who both join the IRA to fight against the English but eventually turn against each other. What the film shows is that those who fight against violent regimes must themselves perpetrate violence to free their people — an unpleasant thought, but very true.

The turning point in the film happens when a treaty is proposed between Britain and Ireland and one faction of the IRA is willing to accept it and the other is not. Damien (Cillian Murphy) is totally against capitulation to the Brits, while his brother Teddy (Pádraic Delaney) feels that the compromise should be embraced.

he film was condemned by British critics (who hated that the British soldiers were seen beating and torturing the Irish — scenes which were based on actual events) and Irish historians who felt that the events depicted were inaccurate. Loach and Laverty were quite eloquent in their defense of the film and explained why they decided to pursue a fictional scenario amidst a depiction of a real historic period.

“‘We wanted fictional characters,’ [Loach] explained, ‘because then they can embody the conflict and follow the rules of dramatic conflict rather than follow what the factual characters would have done in real life.” [from David Archibald, “Correcting Historical Lies: An Interview with Ken Loach and Paul Laverty,” Cineaste, 2007, quoted in Hill, p. 219]

The special nature of the stories told in Loach’s films turns on this idea, that the characters are representatives of certain kinds of individuals in certain situations. When it comes to these situations (which often ended in defeat), the historical advisor on Wind, Donal O Drisceoil, noted, that the film focused on “the ‘what-might-have-beens’ of the Irish revolution, not in a romantic, counterfactual manner, but by highlighting or foregrounding spurned radical political and historical possibilities.” [O Drisceoil, “Framing the Irish Revolution: Ken’s Loach’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley”, Radical History Review, 2009, quoted in Hill, p. 218]

What is of most interest to those familiar with other Loach films is that same classic theme that he has explored since the Sixties: that no one, but no one, betrays the Left better than other members of the Left (who have sought comfort in mainstream political parties or committees). In Wind, it is noted by the intellectual character who is like a mentor to Damien that the IRA has already collaborated with landlords — and this is before the issue of the treaty with Britain has come up.

The measure of Wind’s success is that it revolves around a very old set-up — namely, brother against brother — and makes it seem believable. That is quite an achievement for a film that also wants to put forth a political message about collaboration with those who are selling out the movement they started in.

It's a Free World... (2007) is a peculiar creation by Loach and Laverty — a film where we alternately sympathize and actively dislike the lead character. Angie (Kierston Wareing) gets fired by the bosses at the Polish worker recruitment firm she works at, so she begins her own in her neighborhood in East London She is thus a not only a single mom but a woman entrepreneur who is trying to remain afloat running a business with her best friend.

But she soon begins to cut corners and shaft her workers in the same way her ex-employer did. This becomes a major problem when she starts to use illegal workers. It gets even worse when she isn’t paid by one employer and thus can’t pay her workers — who, in the meantime, are aware that she’s made a big profit off of them. She continues to dig herself deeper into the corruption and by the end of the film has lost her best friend, but is moving up in the recruitment business and is flying overseas to acquire more illegal workers for her scheme.

This is thus an unusual creation for Loach, who usually does want his viewers to identify with his antiheroes and antiheroines. Here, Wareing is charismatic in the lead role and initially inspires some viewer identification, but few viewers will still be liking her when it’s clear that she’ll do anything to make her business succeed. This is complicated by a shocking sequence (certainly shocking for a Loach film, esp. given its sudden violence) in which the workers she screwed break into her house and tell her they’ve kidnapped her son.

This scene is truly unpleasant, but it seems to be have been included to show that Angie isn’t going to suddenly turn back to honest dealings with her workers. As the film ends, she is clearly doubling down in the area that got her humiliated by the workers.

Thus, Free World does still relate to Loach and Laverty’s other work in that it situates the behavior of a working-class character, but it also shows how Angie can move up to the middle class by embracing corruption. A sobering message (conveyed with some great performances), but not a very pleasant one.

Chacun son cinema (2007) (To Each His Own Cinema) is an absolutely beautiful tribute to the moviegoing experience that has never been distributed in the U.S. This anthology film was made for the 60th anniversary of the Cannes Film Festival and features short films by a group of amazing names in international cinema. Included are segments from, among others, Funhouse favorites Olivier Assayas, Jane Campion, David Cronenberg, Amos Gitai, Aki Kaurismaki, Takeshi Kitano, David Lynch, Roman Polanski, Lars von Trier, Wim Wenders, and Wong Kar-wai. I’ve featured segments from the film on the Funhouse TV show and, interestingly, the biggest influences on display here are Godard, Bresson, and Fellini.

Loach was asked to do the British segment and came up with “Happy Ending,” a sublime twist on the theme, in which a working class dad and son stand on the ticket line in a multiplex choosing a film to see, scripted by (who else) Paul Laverty. The choices are all ridiculous (and all but one sound incredibly American).

The key to the piece are the descriptions of the films that the father reads to his son: adventure pic “Warriors of God” (“Action has a new man of iron!”), horror movie “Fiend of Flesh,” sex comedy “Campus Girl-Chase” (“All the action, all the women, half the intelligence!”), dignified romance “Love Across the Ages,” and a British indie film, “Curry and Chips” (which the son notes “will probably be pretty boring”). The best is definitely “Race to Die,” a cop movie described as “A dismembered blonde, a blind man, a three-legged dog — the chase begins!”

The joy of Chacun is seeing how the filmmakers chose to pay tribute to the moviegoing event. Loach goes in another direction and has the boy and his dad not finding any interest in the titles on offer and choosing to go to a football match instead. This conclusion must have tickled the fancy of the producers from the Cannes Film Festival, as Loach's segment is the very last one in the film (except for a brief epilogue, a scene from Rene Clair's 1947 Le silence est d'or).

And yes, while the other filmmakers definitely came up with some deeply moving reasons to love watching film in a theater, Loach’s entry underscores the fact that much of the joy of an empty Saturday afternoon is spending time with one's loved ones, with no obligations and only pleasures to choose from.

Looking for Eric (2009) is the one pure comedy among Loach’s theatrical features, although films like Riff-Raff, Raining Stones, and My Name Is Joe contained a good deal of humor. Interestingly, even here, violence does appear, since this is another working-class comedy (the hero is a postman). A treatise could someday be written about the psychic and emotion violence the state does to the heroes in Loach’s films — as well as the physical violence inflicted from one working-class character to another.

The film also contains the only fantasy sequences in Loach’s theatrical filmography, aside from the dream sequences in Fatherland. The plot itself is predicated on fantasies being had by the postman hero in Manchester, who idolizes soccer hero Eric Cantona. Each time the character is disturbed and ingests pot in some form he dreams he is talking to Cantona, who provides him with life lessons.

As the film moves on, the postman tries to intervene on behalf of his son with a mob boss who humiliates him on video (by having him attacked by a dog) and put the video on YouTube. The postman and his friends decide the best way to pay the mob boss back is to humiliate him on video, with every member of the troop enacting the humiliation wearing Cantona masks.

Thus, Loach returns to the subject of his telefilm “The Golden Vision” by depicting fans who are utterly obsessed with their favorite football team. Here, the “passionate discussion” scene is one in which the fans talk about high ticket prices for the games and the amount of money that the “fat cats” who own the teams have.

The bizarre conclusion is said by John Hill in his book on Loach to “demonstrate the virtues of collective action in response to social ills.” [p. 197] What is most unusual is that the reason our hero needs the advice of Cantona is that he is nervous about having to meet his ex-wife, for whom he still carries a torch. In this regard the film can be seen as a variation on Woody Allen’s Play It Again, Sam, albeit one which toys with the notion that Cantona does indeed know our antihero — one of the guys humiliating the crime boss in a Cantona mask is revealed to be Cantona himself.

Route Irish (2010) is most like Hidden Agenda (1990), in that it is fashioned as a thriller but tackles a real political issue. In this case that issue is the involvement of mercenaries in the occupation of Iraq.

The film takes place in 2007 Liverpool. Our antihero, who served as a mercenary in Iraq with his best friend (with both men taking the job just to earn some money), tries to find out how his friend died. The whole plot hinges on a classic thriller conceit — in this case, a cellphone that the dead friend has in his possession, which contained a video of an innocent Iraqi family being killed by a squad-mate of the friend.Our antihero had an incredibly close relationship with his dead friend (to the extent that the friend’s wife is jealous of their connection). He will do literally anything to get the information he wants and thus we see him waterboarding another mercenary for information. The scene is a grim one — and according to accounts, wasn’t faked at all.

Although the plot is tied up in the machinations of the friend’s death and the earlier killing of the civilian family, the real theme is how the mercenaries were sent to Iraq to protect the population and wound up terrorizing and killing them. As one character succinctly puts it, “If they didn’t support al-queda before [the mercenaries arrived], then they do after.”

The Angels' Share (2012) is a relatively minor Loach, as it starts out in a familiar vein (in a familiar town, Glasgow), initially focusing on the life of a violent young man who is doing community service and winds up becoming a weird comic “caper” film about the theft of extremely rare whisky.

The film is thus perhaps the least of Loach’s theatrical features, ranking with the very uneven Fatherland. We become familiar with the supervisor and members of the community service group that the young man has to join in order to avoid jail time. He hopes to give up his former life of gang violence but is haunted by old enemies. However, the supervisor’s introducing the group to the joys of whisky-tasting and the nuances of whisky preparation seem to exist to introduce a “way out” of their drab life — they will steal an invaluable casque of rare whisky.

The violent undertone is just cast aside here, and the film moves from grim drama to incredibly silly comedy. The caper never makes any sense, except as a contrivance to “elevate” the quartet who undertake it. The unfortunate truth is that the supporting characters are all “types” and the lead is basically a variation on the lead of Sweet Sixteen.

The rare whisky “job” is a gimmick akin to the male-stripper aspect of The Full Monty. And in case we aren’t sure which country we are in, the three young men in the group sport kilts at one point and the soundtrack features the Proclaimers’ “500 Miles.”

Spirit of ’45 (2013) holds a special place in Loach’s filmography, as it was his only theatrical documentary (and his only feature in b&w besides Looks and Smiles). The film’s subtitle is “Memories and Reflection of the Labour Victory” and it has no narrator (titles serve that function). What we see are present-day interviews with seniors who lived through the times depicted and experts who have a solid knowledge of the period, edited together with newsreels and other vintage footage.

The film chronicles the Labour Party’s big win in 1945, at a time when the party was proud of associating the world “socialism” with its behavior. We move through the late Forties and early Fifties, seeing how the nationalization of various aspects of British life brought about a kind of post-war Utopia: There was public ownership of utilities, all forms of transport, and the mines. Not forgetting the sublime socialist model that was and is the National Health Service.Older interview subjects all testify to the absolute bleakness of the 1930s and how the period after the Second World War was in direct counterpoint to that, ensuring that every British citizen had healthcare “from cradle to grave” and was assured a modest but up-to-date house. Several speakers in the film single out the Minister of Health (and housing) Aneurin Bevan as being particularly influential during this period and ensuring that Labour’s promises to the British voter were kept.

These interviews are especially moving and set the stage for the third act of the film, wherein we see how Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government (and later administrations, including those where Labour reigned again) dismantled and privatized every one of the nationalized items except the NHS (which has been chipped away at, so that cleaning, laundry, and catering aspects of the hospitals are all privatized). When this is discussed, of course, the model for what Brits never wanted is what we have in America — a bureaucracy where the insurance firms and Big Pharma dictate what can and can’t be done.

Rather than end the film bleakly, Loach gives pride of place to a senior woman who notes that older citizens of the U.K. need to join with the rebellions staged by younger people (the Occupy movement is mentioned); they need to convey to young people what the post-war vision was and how better life was when socialism was part of Left party politics.

It’s particularly moving to see Loach once again reaching the conclusion that young people can change things for the better, and that they need older people to help them take rose-colored memories and make them into present and future realities. Spirit is an exceptional work, and its function in Loach’s career was obviously to finally address the catastrophic change wrought during the Thatcher years — something he made documentaries about in the Eighties while it was going on, but in every case the doc was either banned or shown on the wrong network.

Jimmy's Hall (2014) offers us a second period piece by Loach set in Ireland. The script by Paul Laverty is based on the life of a real individual, the Communist activist Jimmy Grafton. The film picks up his life in 1932 in County Leitrim, where he has returned after being deported to the United States. He is asked by the locals to re-open a hall that he ran as a collectivist enterprise — community dances were held there, as well as political meetings and classes in everything from poetry to boxing.

The film connects to Loach’s past work in its depiction of the IRA as opposing Jimmy’s efforts, linking them in attitude to the local priest, who absolutely loathes everything Jimmy stands for. One of the best scenes in this regard finds the priest and some sidekicks standing on the road near the hall when Jimmy reopens it, making note of all the local citizens who are headed into a dance.The priest then reads those names out in church during his homily, to shame those who have participated in the sinful act of having a dance. Laverty crafts wonderful scenes for the characters, including a sweet love scene set in the hall, as well as not one but two classic Loach discussion sequences in which the gathered discuss who has the right to the land on which the hall is located. The single best scene (for those who enjoy the clergy being taken down several pegs, like myself) has Jimmy going to confession to basically tell off the priest, noting that he has more hate than love in his heart.

The end basically finds Jimmy back where he was at the outset — being deported back to the U.S. — but the final scene shows young people chasing after the truck in which he’s being taken away, giving him their thanks for what he taught them was possible. In this instance, Laverty and Loach return to a point Chris Marker made in some of his films (most notably The Last Bolshevik), stressing that even failed or long-dormant experiments in activism will live on in the minds of younger people who can carry those same ideas to fruition.

And, possibly in response to the many charges leveled that events in Wind That Shakes the Barley were fictional creations (proven by historians to have actually happened), this film contains a bibliography in its end credits, noting which books were consulted and which individuals (including Grafton’s family) were interviewed to prepare the script.

Loach threatened to retire while making Jimmy’s Hall, but two years later he was back with a film that is among his best. I, Daniel Blake (2016), his second Palme D’or winner at Cannes, is a gorgeous “small movie” (as Godard would have it) with a steady script by Laverty and a heartbreaking performance by lead actor Dave Johns.

The plot follows Daniel, an older man in Newcastle who has had a heart attack. His doctor has told him that he cannot work while in recovery, but the state tells him he has to and thus he has no money coming in while he tries to move his way through the red tape keeping him prisoner. He befriends a single mom in equally dismal circumstances and is heartbroken when he discovers the line of work she has chosen to provide food for her kids.

Throughout, Loach and Laverty meditate on how bureaucracy can destroy a life. Being a senior, Daniel doesn’t know how to sign up for state aid on the Internet and how to look for a job online. He is finally caught in a bind he can’t solve — in which he’s told he must look for work by a benefits worker, but he also can’t accept any jobs he does find because his doctor says not to — which forces him to take a rash action that allows him to regain some of his dignity.

There are numerous scenes that are heartbreakers in the film, but none so strong as one set in a food bank (shot in a real food bank) where the single mom has a breakdown. In the end, we again see that important lessons have been passed on, as Daniel’s aid to the single mom and her kids has resonance for them, and Loach and Laverty once again, with the aid of a terrific cast, deliver an important account of a person just trying to keep his dignity in very harsh times.

In Conversation with Jeremy Corbyn (2016) is a totally straightforward documentary that Loach shot to promote Corbyn’s campaign for leadership of the Labour Party. We watch two meetings (in Sheffield and London) with regular people, who recount their problems to Corbyn. In the last few years both Corbyn and Loach have been expelled from the Labour party.

Sorry We Missed You (2019) continues the mood and message of Daniel Blake, as it follows a family in Newcastle who strive to get by in the gig economy. The husband takes on a horrible job making precisely timed deliveries (with aids like a bottle to piss in as he races to get from place to place). The wife works with numerous seniors in their houses, so she also has a tight schedule, as making sure each senior is cared for could easily stand as its own job.

Like all of Loach’s best, the film offers us a “lighter” beginning and moves to a grimmer conclusion. It also plays like Cassavetes and Mike Leigh, in that we see the family’s very evident difficulties and traumas, but we also know that they will stay together and handle them as a unit.

The film sketches the parents’ job problems but also provides us with scenes that spell out the alienation of their elder child, a teen boy who has taken to avoiding school and spray-painting elaborate graffiti around the town. His parents, suffice it to say, are never home, so one of the nicest moments of bonding in the pic is when the father takes the younger child, a daughter, on his rounds for the day, having her help out as he dashes valiantly from customer to customer.

The system here is the problem, but it has its helpmates, among them the father’s supervisor, who is not willing to make exceptions in any way when he is asked for leniency on a particular issue. He prides himself on the company being the best delivery service in town and so he is uncaring and cruel to the drivers, who all supply their own vans for the job and are subject to constant penalties for anything that goes wrong in the delivery.

There are several moving scenes in the film, and rating high among them are the moments where the wife visits with her senior cases. In one instance, a client shows her pics of a kitchen that was set up during a worker’s strike; in another her hair is brushed by a different senior, who sings “Goodnight Irene” (that wonderful ballad made popular by those tuneful Commies, the Weavers) as she brushes her hair.

As has always been the case with Loach’s films, one is struck by the genuine quality of the performances here. The technical work is also top-notch, as is Laverty’s scripting, which went from strength to strength in the 2010s. Here one of the best moments comes when the couple are in bed after another killer day and the simple line “Everything’s out of control…” is said.

This journey through Ken Loach’s work on this blog now comes full circle, as I reviewed his “last” film, The Old Oak in my first Loach post. I do hope he is able to make one more film — even a doc or a short would suffice. If he is indeed closing out his filmography for real, we can all take comfort in the fact that his films are readily available on disc and online.

Political filmmaking is a dead art, and Loach’s particular kind of fiction filmmaking with a political message is exceptionally rare these days. Watching these films in near-chronological order was an absolute delight, especially seeing how Loach and his collaborators just got better and better as the films were being produced on a regular basis. I do fear that we won’t see this kind of filmmaking that mixes the personal with the political again very soon, but we can only hope that whoever undertakes does it even a fraction as well as Loach did.

Bibliography:

Fuller, Graham, editor, Loach on Loach, Faber and Faber, 1998

Hayward, Anthony, Which Side Are You On: Ken Loach and His Films, Bloomsbury, 2004

Hill, John, Ken Loach: the Politics of Film and Television, BFI, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011

Leigh, Jacob, The Cinema of Ken Loach: Art in the Service of the People, Wallflower Press, 2002