In my last blog entry I noted that there are certain films concerning Rainer Werner Fassbinder that are impossible to find with English subtitles. I’ve learned in the time since I put that post up that some of those films are indeed “on the underside of the Net” with English subtitle files (mostly fan-generated); however, a number of them are still “MIA” as far as subtitles go. However, Jon Whitehead, webmaster and mastermind of the incredible resource Rarefilmm, has now unleashed a wonderful gift for English-speaking, non-German-understanding Fassbinder fanatics in this period between the 77th anniversary of RWF’s birth (May 31) and the 40th anniversary of his death (June 10).

I concluded my last post with a link to the otherwise unseeable The Wizard of Babylon, the 1982 doc by Dieter Schidor, without English subtitles on YouTube. That film was initially distributed by New Yorker Films in the early Eighties and then — poof! — it was gone. Out of distribution, utterly impossible to find. It was SO difficult to lay hands on a copy that I was amazed it was shown again at the Walter Reade Theater in Lincoln Center in November of 2014 as part of an RWF festival. That print, I learned upon attending the screening, was a copy from Australia owned by a university. So, seemingly, that particular copy was the only one available anywhere with English subtitles. Until now.

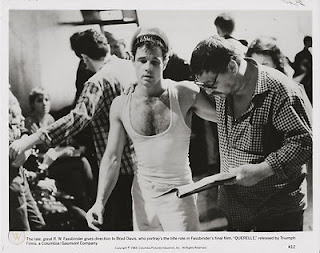

|

| RWF with star Brad Davis. |

Jon went to work on this as a “special project,” and finally, after utilizing different translators, the result is up on Rarefilmm and is now the single instance of a subtitled copy of Wizard appearing on the Internet. The film itself is mostly a behind-the-scenes look at Fassbinder’s last film, an adaptation of Genet’s Querelle of Brest.

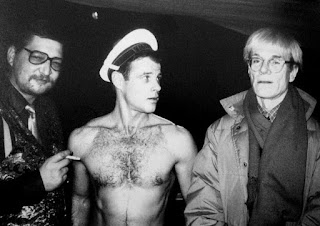

|

| The Warhol poster for the film. |

The making-of part of the doc is actually most interesting when we hear from Burkhard Driest, who wrote versions of the script and played a featured role as “Mario.” Driest disliked RWF’s “very cynical attitude” about manipulating his actors — in this case, Driest questioned Fassbinder about the way a fight scene was to be shot, and Fassbinder taunted him about being scared of doing the scene.

This kind of interview is valuable not because we want to seek out people saying RWF was an incredibly difficult person, but to find out how this attitude was felt by those who were new to his sphere. Otherwise, making-of films become exchanges of compliments and nothing more.

Franco Nero and Jeanne Moreau are in this mode, elaborating how much they wanted to be in the film and how happy they were with their work on it. Schidor questions Moreau about her unique position in the cast, as she was the only person on-set who had ever met Genet. (Who was also contacted to write an opening comment for the film but turned it down; Genet lived until 1986.) She is able to speak about meeting the writer several times but not about his opinion of his work, as he never discussed that with her.

The first revelation is the narration for the film, written in the first and second person (“from” Fassbinder and “to” Fassbinder) by author Wolf Wondratschek, spoken by actor Klaus Löwitsch. It’s quite unsentimental, considering it was presumably written (or could’ve at least been altered) after Fassbinder’s death. It reflects on Fassbinder’s depleted physical state (especially his obesity), his desire for fame, but most of all his drive to keep working no matter what the circumstances or results.

Sample: “I want to be the cover of TIME magazine. I will make it, and that makes me happy, and I admit that. That is luxury. Work when ugliness finally reconquers all beauty.

“A feisty, fat body, a monstrous bastion against any affection that only makes you suspicious. It also protects you from the expected hugs. Even those you shyly long for. Getting ugly is your way of staying alone.

“That’s luxury. How the world’s stars dance in front of your camera, and you’re standing next to them in the shadows with your Bavarian wheat beer. Nothing is more fascinating than being famous. Because nothing compares to the horror when the dreamt-up becomes reality.

|

| Fassbinder, Brad Davis, and some guy who visited the set. |

And then there is the one very important reason to see the film (if one already knows some of Fassbinder’s work): his last interview. As I noted in the last blog entry, while he is less than 12 hours away from death, he does not appear particularly sick, or particularly high. His answers are articulate and well thought out. He does seem very heavy, though, and his breathing is labored. Along with that he seems tired, extremely tired.

But, given that he produced

three early shorts (one is lost to the ages)

one short contribution to an anthology film (the most singularly personal thing he ever made for any medium)

one TV variety special

eight telefilms, two of which were two-parters

one documentary

twenty-eight fictional feature films, and

two miniseries for TV; the second of which, Berlin Alexanderplatz, is arguably his masterpiece and perhaps his most personal fictional work

it makes perfect sense that he finally, sadly, was very tired at the age of 37 and very much needed to rest on June 10, 1982.

You can access The Wizard of Babylon at Rarefilm at this link. Make up your own mind as to whether Fassbinder’s final interview is something that should be hidden away from RWF’s fans (as his mother desired) or if it is a very important document in terms of understanding Fassbinder’s thoughts at the end of his life, as some of us believe.