Robert Staats served just that purpose in a number of cult films that are great to begin with; he also walked away with some great moments in films that are not quite up to snuff. And the most intriguing thing about this is that Staats has never considered himself to be an actor, didn’t want to be an actor, and firmly maintains to this day that his parts in movies came about because he was fine with “doing a favor for a friend.” What goes unsaid here is the filmmakers in question — Harry Hurwitz, Jonathan Kaplan, Robert Downey Sr., and others — knew that Staats could give a memorable performance and they wanted him to brighten up their movie with his cinematic alter-ego: a carny pitchman who is both your best friend and a guy whose hand is reaching in your pocket.

I had the rare pleasure of interviewing Mr. Staats a few weeks ago and am very happy to share some of his history, his wonderful anecdotes, and his not-too-positive view of major-studio Hollywood (countered by his friendly devotion to Hurwitz and the filmmakers who knew how to use him as a “secret weapon” to keep their films moving along perfectly). He’s a no-nonsense sort of guy who, at 89, is happy that he has fans who enjoyed his movie work, but he’s far prouder of his military service and his work as a seaman over the years.

“I have no interest in any aspect of show business,” he says now. “I was not interested in soliciting any acting work. I had no agent, although I got a lot of offers from agencies. I wanted no part of it. I would answer the phone and someone would introduce themselves, ‘Could you do this or that?’ ” That was the extent of his work in show business, although he clearly got a number of those phone calls from 1969 through the early Eighties.

|

| Winning over a rube in Fairy Tales (1978). |

One of his initial forays into show-biz was investing in a traveling show that would honor James Dean, who had recently died. The show contained a facsimile of Dean’s “death car” and was to feature a lifelike wax figure of the movie idol. When the figure arrived, however, it was a dummy of Elvis Presley — the man who made the figure thought that Presley was Dean and had no idea what the real Dean looked like.

Despite that screw-up, the attraction did fairly well and Staats ended up selling it (and the giant semi-trailer the car was kept in). He was then asked by a producer of tent shows if he could step in as a front-talker. “I did very well — stayed there and made quite a bit of money.” He did spiels at large events. “Some of these state fairs had 100,000 people on the midway in one day. These were huge things, the Calgary Stampede, the Texas State Fair.” He would entice the public to see attractions like “the Alligator Boy.” He admits that being a front talker is certainly an art, but not a nice one — “painting is a nice art. I was screwing people out of their money.”

“By the way, every game in the carnival is rigged. Every one. I know how they’re all rigged. I know so many ways...”

In the off-season, he started pitching merchandise, but he felt that he “didn’t have a very good resume” at the age of 30, so he and his wife both re-enlisted in the service so he could get a commission. When his second stint (1959-62) in the Army was over, he made a crucial connection that propelled him into the advertising business and ultimately into a film career he never asked for, but that he excelled at.

A photographer named Ray Porter that Staats knew from the Army was then working for Seventeen magazine. He had gone to art school with an animator named Len Glasser. Porter introduced Glasser to Staats without knowing he was introducing future business partners who would change the face of advertising with their unconventional approach to industrial films and TV commercials.

|

| Animation from "Safety Shoes." |

Staats “backed into” the film for an interesting reason — it simply wasn’t long enough. The sponsor wanted a 20-minute short and the film was running under. Glasser had hired doubletalk expert Al Kelly to provide a very funny and incomprehensible intro, and had created a cartoon about safety shoes (which features, among others, the [uncredited] voice of future Hurwitz star and Staats cohort Chuck McCann).

He needed to fill out the spoof section of the film, and so Robert Staats became a film actor, playing his alter ego, later named “E. Eddie Edwards.” Staats says he chose that name for a specific reason: “It just struck me. There are a lot of shitty guys who always try to make themselves look good with a nice name. So E. Eddie is this shitty pitchman, this dishonest carny who wants to be something else. He was like a number of guys that I knew that were that way.”

Staats wrote his own lines and both sold the product and made fun of hard-sell con men whom every consumer has come in contact with. The character blossomed later, especially in the films of Harry Hurwitz, but here he comes on strong and is a memorable creation. In other words, Staats stole his very first film.

“Safety Shoes" was up online on Vimeo, posted by a noted advertising filmmaker. And it's now gone! All we have left is this screengrab of Bob as E. Eddie.

and this credit for Staats:

and this production credit for the Big RS:

Glasser’s company ended up having ancillary offices in Chicago and Toronto, and doing films for big clients like the Ford Motor company, General Mills, and Hostess. Staats appeared as a TV-friendly version of his E. Eddie character in a string of TV commercials for New England Telephone. (Staats notes his pitchman character was family-friendly in these spots — “I would clean it up.”)

The first great independent filmmaker that Staats worked as an actor for (albeit briefly) was Robert Downey Sr. (My recent tribute to Downey Sr. can be found here.) Again, happenstance and blind luck took a hand — “Downey and I lived in the same building in Forest Hills. My son and Robert Downey Jr., and my wife and Downey’s wife, would meet all the time. [Downey Sr] wanted to be in the film business and I was in the film business. I told him about this crazy filmmaker in the same office building as Stars and Stripes, a millionaire who was pumping a lot of money to build up a commercial film business called Filmex.”

The man who ran Filmex was an heir to a very profitable business, American Home Products. His family was wealthy and he was “wiping them out financially” since nothing was coming of the film projects he invested in (which included commercials). He hired Robert Downey Sr, who wound up sitting around and writing his own films, including a spoof of advertising that was to become Putney Swope (1969).

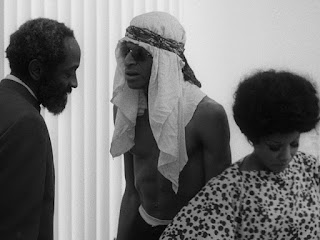

Downey’s ideas came to nothing at Filmex, but his experience working at the firm did inform part of Putney Swope, and so the man who connected him with the film biz, none other than Staats, was hired to play a small part in the film. (An executive, called “Mr. War Toys” in the credits, who is told he has bad breath by Arnold Johnson as Putney; the scene can be found here.) Staats remembers the shoot well, as it took place in an office building at night.

|

| Staats in Putney Swope. |

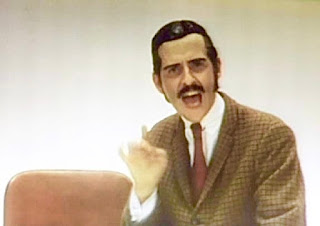

But before we get around to Staats’ awesome scene-stealing in Hurwitz’s best known (and best in general) film, let’s turn to a different medium. Staats’ work in Len Glassman’s advertising films attracted the attention TV producer George Schlatter, who was cresting in 1968-69 on the incredible success of “Laugh-In.” After a nice luncheon at the Russian Tea Room, Schlatter hired Staats to appear in and write for his new series, “Turn-on.”

|

| "Turn-on" Photo by S. Kaufman. |

Staats is very frank about the experience of working on “Turn-on.” He was hired for 14 shows and claims that many of his segments for that season were shot. (One other complete episode, in addition to the infamous first show, is in the library of The Paley Center.) He says he performed as three characters: his pitchman alter-ego E. Eddie, a “Modren Bride” [spelling correct] who gave advice to the lovelorn, and “the Magic Housewife” who dispensed cooking tips. He wrote his own material and maintains that at no time was it said by anyone associated with the series (including reps from the network, ABC, or the sponsor, Colgate Palmolive, who were on the set) that the show was objectionable.

|

| "Turn-on" Photo by S. Kaufman. |

He admits his sketches were “slightly smutty” for 1969, but he was encouraged in that by Schlatter. He also looks back on it as a lessons of sorts, since he came out of the experience feeling that “Hollywood is a dishonest sewer” that he was happy to be away from. (And, aside from one very well-budgeted film he appeared in as a favor to director Jonathan Kaplan, Staats never worked in mainstream show biz again.)

Staats also notes that, after the first “Turn-on” episode aired, he was more than surprised to see the “Art Fern” character on Carson’s “Tonight Show.” The character had many aspects of the E. Eddie Edwards character and Carson worked with Carol Wayne, who had played Staats' sidekick on Schlatter’s show.

|

| "Turn-on" Photo by S. Kaufman. |

We move on to the point where Staats first worked with the filmmaker he is most identified with, the late and very great Harry Hurwitz. Staats has nothing but praise for Hurwitz, declaring that Harry “was a wonderful guy — there was no artifice about him.” As Staats remembers it, he was introduced to Hurwitz by Kaplan (who studied at NYU in the 1960s, with Scorsese as his tutor). Other directors might’ve used Staats to good advantage in bit parts, but Hurwitz constructed entire scenes around the E. Eddie Edwards character and cast Staats in his only starring role (in The Comeback Trail).

|

| McCann and Hurwitz. |

Hurwitz realized that to get the best out of Staats he should give him an outline and let him create his own dialogue. But, Staats emphasizes, this was within “parameters” — “I made it a pitch, but I made it his pitch. Some of the key lines were Harry’s. You can’t write a pitch. I can write a pitch because I was a talker. There’s a singsong rhythm to it — if you don’t do that, it doesn’t come across. All that stuff I did [in movies], I had to be the writer completely or rewrite it, so that it fit E. Eddie’s pitch.”

|

| Demonstrating proper behavior in The Projectionist. |

The result in Projectionist is a sequence that is very well-remembered, not only for its un-p.c. jokes and spot-on spoof of late-night scam-product commercials but because it stands as a little mini-film within the larger film. In her review of the film, Judith Christ singled out Staats for praise. This short segment showcases the full-tilt version of E. Eddie, and while The Projectionist is a modern comedy classic (and nostalgia-fan’s wet dream), the film is indeed stolen by Staats for the mere three minutes that he’s onscreen:

Staats next appeared in Jonathan Kaplan’s Night Call Nurses (1972) at Kaplan’s request. Staats had no agent and, again, appeared in films simply because the filmmakers (Downey Sr, Hurwitz, Kaplan, Alan Abel) would call him up. Here again Staats ad-libs for a few minutes as E. Eddie, lending some verbal humor to a “soft” T&A drama-comedy (and stealing the film in the process). His bit in the film begins at 18:54; the film is here.

|

| In Night Call Nurses. |

This means that there are two different versions floating around the “underside” of the Internet (there has never been a DVD or even a VHS release of the picture). The first one contains more of the main plotline, while the second ends up exploring the fictional film company that is at the center of the plot.

I actually “found” Mr. Staats because of that piece. I had asked the public for any info regarding his status — who was he? Where had he come from? Was he still with us? This lead to the interview I’m writing about here. In the meantime, a remake of the Hurwitz film has been finished and awaits a major release — it stars Robert De Niro in the Chuck McCann role (I’m not making this up; check out the trailer), Tommy Lee Jones in the Buster Crabbe role, Morgan Freeman in newly created gangster role, and Zach Braff of TV’s “Scrubs” in the role played by Staats (this time as “E. Eddie Eastman”).

|

| McCann and Staats in The Comeback Trail. |

He also noted about the film’s plot — about two low-rent producers trying to kill the senior-citizen star of their latest film (Crabbe) in order to get his life insurance — that “anybody who saw The Producers would recognize it in Harry’s outline.” He noted that McCann and he ad-libbed their own dialogue throughout the shoots. “Harry gave us a few minutes of direction,” he emphasizes, with “no time estimation” given for the scenes but with the caution “don’t run away with it. You could say we were script writers,” he clarifies. “We wrote dialogue — we were dialogue writers.”

He denies the story that was in my original blog entry (courtesy of an associate producer on the film) concerning Buster Crabbe getting drunk and beating someone up on the set. Staats does confirm that Buster was fond of “beverages.” (“I’m fond of beverages myself,” adds Staats.) But he didn’t beat anyone up on the set.

|

| Crabbe in The Comeback Trail. |

“A couple of years later Buster was giving a talk to a bunch of film students at a college. He called me and asked me to come and help him out with the talk. He liked me and I liked him.” As for Crabbe beating people up, Staats declares it never happened on the Hurwitz film. He says, “I knew him well — not quite well – enough to judge his character. I mean one of the things carnies do is figure out people… so we can take their money. ”

I was surprised to see that Hurwitz’s film is back “in public view.” This is the original edit of the material, with more of the plot than the later version:

A 1976 film that Staats appeared in has disappeared over the years. Alan Abel’s The Faking of the President is present only on the Net as a listing of a handful of cast members, including Staats as G. Gordon Liddy and the infamous “Richard M. Dixon” as Nixon. The info we can go on is Staats’ vague memory of the picture: His character name was “G. Gordon. He was a pitchman; he sold a line of weaponry.”

The next filmic adventure for Staats was a bit part in Jonathan Kapan’s first mainstream production, Mr. Billion (1977), made as an American vehicle for Italian star Terence Hill. Staats appears in the film as railway train conductor who is (of course) running a side hustle in cheap watches.

|

| In Mr. Billion. |

Staats’ memory of the film extends to the fact that it was the only film he was in that had a big premiere — the film played as the Easter show at the Radio City Music Hall. “Jesus, that stunk!” Staats reflects on his friend Kaplan’s first big-budgeted film. (Kaplan did better with later items like Heart Like a Wheel and The Accused.) His scene in Mr. Billion can be found here at 18:45.

|

| In Fairy Tales. |

He got the part in the usual way — Hurwitz called him up and offered it to him. Staats was once again “doing whatever Harry wanted me to” and he made the role his own by ad-libbing carny pitches to rubes who wander by the shoe. His tagline from his previous E. Eddie appearances comes in early on. (“Isn’t that wonderful? Say yes, it makes me feel good. I couldn’t help but notice... ”)

He returns throughout the film to instigate the vignettes, with wonderfully worded enticements. (“20 dollars for sex, 30 if you want to touch the sides.”) At the end, he closes things out with an exhortation to see the film again, with your family: “It’s a family picture, friends. Mom and the kids can come for the music and dancing, and Dad will enjoy the meat.”

|

| In Fairy Tales. |

One can only be grateful to the YouTube poster who boiled down Staats’ scenes in the film to one glorious 10-minute edit. The man himself notes that he doesn’t keep copies of his acting work around, but he was amused when a relative stumbled onto Fairy Tales and was surprised that he had been in a “porn” movie. (It's actually a softcore picture.) Staats’ take on the movie? “I thought it was funny — I love that kinda crap!”

Hurwitz’s second softcore film as “Harry Tampa” was Auditions (1978). The premise for this one is tissue-thin: We watch people audition for the sequel to Fairy Tales. The participants are mostly porn stars who perform for the camera solo or in groups. There is comic relief every so often — Staats wanders through, of course, and gets two really good scenes (and a bit toward the end). This time his E. Eddie Edwards character is a sleazy agent (for “ASU — the Agency for the Strange and Unusual”), but that’s sort of like being a pitchman anyway, isn’t it?

|

| In Auditions. |

The second part of the film was shot in L.A. and it’s very different in tone. (And much less funny.) The latter-day productions of Adequate Pictures includes a “where did this come from?” charity-single music video sketch that is clearly a riff on “We Are the World.” In this part of the film the cast includes a young Bruce Willis, Robert Downey Jr, Richard Lewis, and many other L.A. standup comics.

Staats’ turn as E. Eddie finds him as the MC of a movie premiere where he sings the praises of the studio’s output, including “Singin’ in the Synagogue.” His bit is at 10:29.

One of Staats oddest credits was a very mainstream cartoon assignment — doing a voice for the syndicated show “Drawing Power” in 1980, which was half-live and half-animation, and was a spinoff of the popular “Schoolhouse Rock” series. “George Newall and Tom Yohe worked for executives at an ad agency called McCaffrey & McCall (which I wrote two live trade shows for, and I appeared in the shows). They were potential clients I called on. So I got to know George very well, and they had this very successful show they owned called ‘Schoolhouse Rock.’ Periodically they would call me up to do voiceovers.”

I must, again, bless the fans on YouTube who upload everything they love. A VHS video of “Drawing Power” has been uploaded and looks to be shot off a TV set. Staats does the voice of “Professor Rutabaga” who is, you guessed it, a carny pitchman! The character appears at 10:49 and 39:01, as the Professor lectures us on the joys of vegetables and our imagination. He even says “Say yes — it makes me feel good...”

The last time we were lucky enough to see Staats steal a picture was in Kenny Hotz and Spencer Rice’s mockumentary Pitch (1997). As Staats tells it, “Two young guys up in Toronto wanted me to do the film. I didn’t know them. I agreed to do it, if they had refreshing beverages on the set… and some sandwiches.” (Mr. Staats never specified which beverages he was looking for, but one can sure it wasn’t a seltzer or a Coke.)

Staats appears at 11:06, 28:30, and 51:34:

For those who are Hurwitz completists (tell me, where is his own Nixon film, Richard?), Staats brought up another collaboration he had with Harry and Chuck McCann, which evidently was never edited together (or sits in a vault somewhere). “Chuck was in the film; he had the lead. He plays a homeless guy who gets a credit card and uses it to buy food or something. He’s a very simple guy. He then gets a second credit card — you know, how they mail them out to people? So when he gets the bill for the first one, he pays it off with the second one, and back and forth. It was shot on Long Island; Harry was a hired hand directing it.”

Another Hurwitz fragment with Staats sounds like it would’ve possibly been woven into another Hurwitz “omnibus” pic like That’s Adequate: “Harry asked me to do a pitch in an amusement park in Long Beach, California. And it had to do, I think, with politics. I don’t know what became of it. It was dark — it was like an evil pitchman luring you into a tunnel ride. This was near the end of Harry’s life.”

|

| Making a point in Auditions. |

“Merchant seamen are roughnecks, hard-drinking guys. But they’re also very intellectual, believe it or not. They’re readers. I knew two millionaires who went to sea — they had a million dollars and they’re shipping out as seamen, not just once, that was their life. It has its appeal…

“It isn’t romantic — they love the life! The sea wants to kill you, every fucking day. And it does, frequently. Seamen have a very high rate of dying or getting injured. That goes with the territory. Ships blow up, collide, shoal up, burn out at a rapid rate. It’s the nature of the thing. Nature is a powerhouse.”

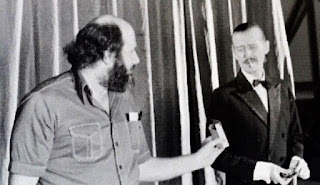

At different points in our interview, Staats pointed out that he was only an actor because “people called me up.” He did note, more than once, that he had the best working relationship with Hurwitz: “Harry was very gentle, but also very strong. He knew what he wanted, and he got it out of us.”

|

| Hurwitz and Staats, working on The Comeback Trail. (Photo by S. Kaufman.) |