Following in the wake of a Hammer binge I went on for a few months in 2022 and an Amicus one last year (my reviews of the films are here), this Halloween I watched all the British horror films produced and distributed by Tigon British Film Productions. For the record, a tigon is an animal that was sired by both (take a guess) a lion and a tiger.

The first two films I watched would make a neat double bill called “Boris’s waning years.” The Sorcerers (1967) was the beginning of the final, “sad” period in Boris’s career — Targets is the best of this bunch, but in every one of his eight last onscreen films (including a quartet of bizarre Mexican flicks), he’s present for a limited amount of screen time. Sorcerers was clearly scripted in a "cloistered" fashion because Boris wasn’t very mobile in his last years. (He suffered from very bad arthritis.)

Thus, he’s a bearded, low-rent hypnotist/scientist who decides to go for broke and recruit a “hip” young man (he goes to discotheques!) to be a subject for his hypnosis machine. Boris and his surprisingly malevolent old wife (Catherine Lacey) end up controlling the boy, with the wife making him commit bigger and bigger crimes. Thus, both Boris and Lacey are almost always in the dining room of their apartment (except for an early moment at a local store and the hypnotism-machine scene, in which a lotta psychedelic colors are seen playing across the young man’s face).

As always, Boris took his work very seriously, and so he gives more to the film than the scripters and director (who one year later made the sublime Witchfinder General) actually did.

Boris is more of a guest star in The Crimson Cult (1968, aka Curse of the Crimson Altar; Tigon films often had diff names for diff countries), which finds an antiques dealer searching for his missing brother, whom we see selling his soul to witch queen Barbara Steele in the opening “dream” sequence (but it’s not a dream!). That entertaining opening scene is shortly followed by an all-out “young person’s orgy,” in which lots of “wild” things are seen (but everyone remains clothed in one way or another). The rest of the film is the classic setup of the protagonist searching for a missing person in a “climate ruled by evil.” (Derived in this case from the Lovecraft story “Dreams in the Witch House.”)

In this case, that’s embodied by Christopher Lee (who, like Karloff, took his work very seriously and is seen giving a solid performance despite wearing an awful fake mustache). Boris appears in a wheelchair in all his scenes here, as an expert on witchcraft — the big twist is that he is *not* in league with the witchcraft brigade in town. The ending indicates that Lee was in fact operating pretty much on his own in terms of evil AND he may not just be a descendant of Steele’s character but might actually *be* her!

|

| Barbara Steele, in all her elegant villainy. |

The measure of a great horror actor is how much he/she commits to the part. Peter Cushing was one of those who always took his work very seriously onscreen, no matter how ridiculous the film was. Case in point: The Blood Beast Terror (1968), a pic in which he plays a 19th-century police detective investigating a series of murders in which the victims were drained of their blood.

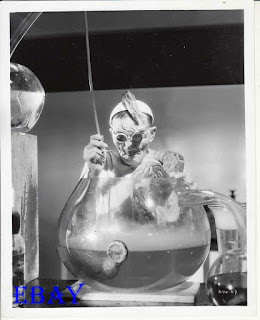

|

| The moth monster in Blood Beast Terror. |

Cushing reportedly later cited it as his worst film (and that's going some -- he was a game old gent, but he made some real stinkers). This is reflected in the film's last lines when a bobby says to him, "They'll never believe this back at the Yard" and Peter responds, "They'll never believe it anywhere!" True, very true, Mr. C.

One of the two masterworks that Tigon made, The Witchfinder General (1968, aka The Conqueror Worm in the U.S, replete with Price reading the poem) finds Vincent Price giving one of his most impressive performances as an out-and-out villain, the real-life “witchfinder” Matthew Hopkins (who reportedly gave himself the “general” title). The film is an incredible work, because it was made on a schlock-level budget, with Tigon getting extra $ from American International Pictures (which initially considered it a tax write-off, but then was surprised to see how good it looked given the money spent).

|

| Vincent Price at work in Witchfinder. |

|

| The sleazy U.S. poster for Witchfinder General. |

The film’s ultimate statement about the nature of man is found in the fact that the soldier’s comrades (the Roundheads serving under Cromwell, who is depicted here, warts and all) are also seen as brutal thugs. The lovers (and the victims of Hopkins’ tortures) are the only sympathetic characters in the film, and Price was only on a few occasions at this level of nastiness. Vinnie supposedly had major blow-ups with director Michael Reeves (who sadly died after this film at only 25, of a problem with a sleeping drug), but he later admitted that the film contained “one of the best performances I’ve ever given.”

The kind of deadpan fantasy that has been mocked mercilessly in things like “Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace,” The Body Stealers (1969) is a tedious Tigon flick that has a nominally intriguing premise — parachuting paratroopers are disappearing in mid-air! — and then spins a dire tale about the aliens who have kidnapped Britain’s finest flyers (who have also been trained to go into outer space — a detail that is planted early on and which doesn’t get referenced again until the very end of the pic).Poor George Sanders and Maurice Evans are the biggest names in this picture (Sean’s brother Neil Connery is the next-biggest, to give you an example), and boy, there are *reams* of dialogue that the performers have to recite before we even get the “thrill” of the end revelation about the aliens (who take the form of Maurice Evans and a beach-babe whom our hero falls for — perhaps a rip from Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which Tigon’s title clearly was making reference to).

You’ve got to take the bad with the good in a binge of the productions from a studio that was really cranking ’em out between 1967 and 1972. (Otherwise, Tigon distributed films from ’64 to ’83.) Certainly, The Haunted House of Horror (1969, aka Horror House) is a stinker from the studio, a fun time-capsule but a crappy horror flick. The plot finds a group of twentysomethings getting bored at a swinging party and so they decide to go to a haunted house and have a séance. (Sure, what else ya got?) The romantic entanglements of one trio in the group are insipid but worse are the terror scenes in the haunted house.

|

| Frankie, fresh from the land of beach blankets. |

Much more intriguing is The Beast in the Cellar (1971), which has a “monstrous” serial killing plot superimposed on a far more interesting, nearly theatrical in nature (all set within one house), tale of two senior citizen sisters (Dame Flora Robson and Beryl Reid) who have kept a secret for three decades walled inside their basement.

|

| Beryl Reid threatened by the "Beast." |

Reid particularly skillfully handles a long monologue that explains the story behind the titular “beast,” which is simply the story of a family that didn’t want its young man to go off to war. Here there are no big surprises in terms of the murder plotline, but one feels something very rare in terms of these horror quickies — the feeling of having seen a top-notch bit of acting.

The second of the two Tigon masterworks, Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971, aka Satan’s Skin) goes its predecessor (The Witchfinder General) one better by having no sympathetic leads. (Two young lovers appear at the beginning here, and the young woman is soon taken off to Bedlam, sporting a Satanic claw-hand!)

|

| Blood on Satan's Claw. |

The film is considered a seminal work of folk horror, and that it is, in that it offers a city/country opposition. (The town doctor tells a visiting judge, “You come from the city. You cannot know the ways of the country.”) It also shows the brutality of both sides in this equation, much like The Wicker Man. It was badly reviewed and was a box-office dud on first release, but over the years it has become a cult classic and has been stolen from quite often. It has an often sublime nastiness.

|

| Linda Hayden as the teenaged witch priestess. |

The plot follows a Mama’s Boy and his Mama, both of whom are members of the minister’s cult (called “the Brethren” and run by a preacher in Arizona!); the chapel also happens to be in one room of their house. The son is a security guard who is the titular fiend who murders women and makes audio recording of the moments leading up to their deaths and then plays them downstairs when it looks like he’s readying for a bloody good wank (but British films of this period couldn’t go that far, so we just see him visibly excited listening to the tapes).

|

| Patrick Magee in all his anguished glory. |

The sisters go on a photo shoot at a country house and quickly find (in a rather blatant admission – no mysteries here!) that the people in the house and the nearby area are all in a coven of witches. The film ends up becoming a battle of wills between the more severe of the two sisters and the modeling agent, who is also the high priestess of the coven. The film is not exceptional in any way, but it does deliver on its nudity (and some simulated sex) and Satanic sabbath requirements (not just one, but two sabbath scenes).

A big name in low-budget British horror, Pete Walker made his full transition into horror from sexploitation with The Flesh and Blood Show (1972, distributed by Tigon; independently produced). Here the producer-director offers up a tale that sits as a kind of midpoint between Agatha Christie’s whodunits and the “young people are murdered one by one” trope that became standard stuff for the Friday the 13th series.

The plot involves a troupe of young performers who venture to a seaside town to rehearse an extremely dubious stage show to be called “The Flesh and Blood Show.” A few of them are killed in succession, and one of the seeming red herring characters is indeed revealed to be the killer.

The only “name” in the cast is Robin Askwith, the very busy actor who is best known for starring in the “Confession of a...” sex-comedy series. The film is neither great nor terrible, although it is about 15 minutes too long. The oddest element thrown in is that the flashback that explains the murderer’s motivation is in b&w and was shown in 3-D at the time of the film’s release.

One of the more curious hybrids among the Tigon productions is Doomwatch (1972), a film derived from a BBC series (1970-72) that had an environmental take on the sci-fi and thriller genres. The film definitely has a folk horror premise, in which a doctor from the “Doomwatch team” (a government org investigating environmental threats) played by Ian Bannen comes to a small island to investigate a weird outbreak among the villagers living there. Thus, the first half of the film operates on the level of folk horror, with Bannen being shunned by the villagers who have lived there for generations. Many of the villagers are suffering from various stages of acromegaly and violent tempers (that result in murders and suicides).

|

| The acromegaly-afflicted villagers in Doomwatch. |

Overall, the film has as many “tough cop crime show” moments as it does horror and thriller ones, including a bunch of tedious moments where Bannen comes back to London and stands in an office, learning about the cause of the problem. The appearance of the villagers is alarming, but that’s more about connecting to the viewer’s natural fear of decay (or more simply, aging) than anything truly horrific.

The last horror film produced by Tigon, The Exorcism of Hugh (1972, aka Neither the Sea nor the Sand), is a “love knows no boundaries” drama that only becomes horrific in the last 20 minutes (and even then is still more of a romance than a terror flick). The plot concerns a married woman who falls madly in love with a man who lives with his brother on the island of Jersey.

The couple fly to Scotland, where the man dies — but then reappears to the woman, unable to speak or stop staring at her. She is so thrilled to have her lover back that she stays with him on the trip back to Jersey. His brother tries to get him to an exorcist but is killed on the car ride there. The final scenes have the heroine recognizing that her beau truly is dead and at first staying away from him, until she decides that she wants to spend eternity with him, by walking into the sea.

|

| The heroine feels her lover's crumbling caress in Exorcism of Hugh. |

There is no better way to end this survey of Tigon’s horror movies than to review the very last horror movie that Tigon distributed, especially since it featured the two greatest British horror stars of the period. Post-1973 the studio served as distributors primarily for sexploitation fare, with the exception of oddities like the Spike Milligan comedy The Great McGonagall (1974) and the Clash film Rude Boy (1980).

|

| Cushing tries to sell threadbare horror, and succeeds. |

The plot is utterly ridiculous but goes back to the many of the tropes of the great “mad scientist” monster pics of the Thirties and Forties, in which a doctor starts off with a humanitarian motive and then all goes awry when his creation threatens mankind. In this case, Cushing is the doctor who is telling the tale in front of a bright white wall in a room. (Those who watched the recent “Twin Peaks” reboot will remember this white-wall notion being present in Sherilyn Fenn’s closing scenes.)

Cushing tells us how he found an oversized skeleton in New Guinea that was a kind of deity to the people of that area, a monster whose skin would evolve during rainstorms and then introduce evil into the world. Cushing takes the blood from the skin that develops on the skeleton and then makes a serum including it. He decides for some unfathomable reason to inject the serum into his beloved daughter (who is having a freakout over finding out that he hid from her the fact that her mother was in asylum for decades — an asylum run by Lee!).

Thus, the film includes not one but two monsters (and a super-strong escaped mental patient who serves as a red herring): both Cushing’s daughter, who becomes both feverishly slutty and violent, and the skeleton, which by the end of the film (during a rain storm!) develops a full covering of skin (and then wears a cloak it found somewhere). The denouement can be figured out quite easily from the opening scene with its bright white backdrop, but there is still much fun to be had from the proceedings, especially when Cushing is being anguished (which is basically for the whole picture) or Lee is being mean (ditto).

Horror movies lost ground in the mid-Seventies, and so the British horror studios simply stopped producing them and started making and distributing other fare. Although Tigon’s filmography as a whole doesn’t hold a candle the productions of Hammer and Amicus, there are still the two folk horror masterworks and some pleasant surprises in other films, most especially some great bits of casting, from Karloff to Beryl Reid, Patrick Magee, and certainly Lee and Cushing.

Note: The above films can all be found on DVD/Blu-ray and in very watchable condition on the Ok.ru site.