With old Hollywood coming into view again, thanks to the extremely corny Feud miniseries (Robert

Aldrich fans, take arms!) and the recent Oscars (which contained a few

blink-and-you’ll-miss-‘em old film clips), I’ve been thinking of the study of classic

Hollywood films. The other occurrences that brought out these thoughts were the recent deaths of Richard Schickel and TCM host Robert

Osborne. Since I have nothing special to offer in the way of tribute to those

gents, I will move back to a writer whose work I’ve wanted to return to for

some months now, Richard Corliss. I intended this piece to appear on his

birthday (March 6), but it will appear instead near the anniversary of his

passing (April 23, 2015).

In the Deceased Artiste piece I wrote about “RC” (as I was acquainted with him — I felt awkward calling him “Richard” in our correspondence) I noted that he wrote with particular elan and touching fellowship about his critic-friends when they died. I thought about the fine tributes I’m sure he would’ve written for Osborne and his old colleague Schickel and realized it was high time to return to Corliss’s writing.

He published only four books, and all but the last are out of print. The longest and most significant is his first, Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema (1974), which now stands as the only “collection” of his reviews (unless his best Film Comment and TIME pieces are ever put together between covers). It was his first “grand statement,” a defense of the Hollywood scripter that reacted as a kind of corrective to his teacher and friend Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema. As such, it’s an unusual book — to fully get what Corliss is doing you’re best served having at least read some of Sarris’s book, which was in itself a grand statement, in which Sarris ranked Hollywood directors from “Pantheon” masters to “Less Than Meets the Eye.”

In the Deceased Artiste piece I wrote about “RC” (as I was acquainted with him — I felt awkward calling him “Richard” in our correspondence) I noted that he wrote with particular elan and touching fellowship about his critic-friends when they died. I thought about the fine tributes I’m sure he would’ve written for Osborne and his old colleague Schickel and realized it was high time to return to Corliss’s writing.

He published only four books, and all but the last are out of print. The longest and most significant is his first, Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema (1974), which now stands as the only “collection” of his reviews (unless his best Film Comment and TIME pieces are ever put together between covers). It was his first “grand statement,” a defense of the Hollywood scripter that reacted as a kind of corrective to his teacher and friend Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema. As such, it’s an unusual book — to fully get what Corliss is doing you’re best served having at least read some of Sarris’s book, which was in itself a grand statement, in which Sarris ranked Hollywood directors from “Pantheon” masters to “Less Than Meets the Eye.”

Sarris was the foremost American proponent of the

Cahiers du Cinema’s “politique des auteurs,” but he was

quick to admit that that approach to film history did have its problems.

Foremost among them were the Hollywood productions that were perfect films, but

not particularly because of the director (Casablanca being

the best example). He also included a chapter called “Bring on the Clowns!” in

which he admitted that the great American film comedians who never received

directorial credit on their films were still the “auteurs” of said works — when

you see a film starring Laurel and Hardy, W.C. Fields, Mae West, or the Marx

Brothers in their prime, it doesn’t matter who directed it, the film’s “life

force” (and co-scripter) is the starring comedian.

A film critic who had tastes that ranged far and wide culturally, Corliss decided to extrapolate on this particular theme by discussing the screenwriters whose work was so consistently excellent that they outshone those who directed their work. The book was written over a three and a half year span and includes rewrites of some of his pieces for magazines and other publications. He discusses 100 films written by 35 carefully selected scripters.

It’s a curious book to read in this era when media surrounds us everywhere, but then so are all the serious film books written in the latter half of the Twentieth Century. Talking Pictures also comes from the time when people other than academics would read serious film books. The filmgoing culture that took mainstream, and more particularly old and foreign, films seriously was at its height from the Fifties through the Seventies (the election of a B-movie actor curiously did a lot to kill off cinema appreciation in America). Reading these books one gets the sense of shared enthusiasm — from the best-selling books of Pauline Kael to erudite fare like Peter Wollen’s Signs and Meanings in Cinema.

A film critic who had tastes that ranged far and wide culturally, Corliss decided to extrapolate on this particular theme by discussing the screenwriters whose work was so consistently excellent that they outshone those who directed their work. The book was written over a three and a half year span and includes rewrites of some of his pieces for magazines and other publications. He discusses 100 films written by 35 carefully selected scripters.

It’s a curious book to read in this era when media surrounds us everywhere, but then so are all the serious film books written in the latter half of the Twentieth Century. Talking Pictures also comes from the time when people other than academics would read serious film books. The filmgoing culture that took mainstream, and more particularly old and foreign, films seriously was at its height from the Fifties through the Seventies (the election of a B-movie actor curiously did a lot to kill off cinema appreciation in America). Reading these books one gets the sense of shared enthusiasm — from the best-selling books of Pauline Kael to erudite fare like Peter Wollen’s Signs and Meanings in Cinema.

|

| RC meets "rock-teur" Chuck Berry |

Corliss’s notion of reworking the auteur theory to shine the light on writers rather than directors thus fit perfectly with the times. Sarris himself admitted that there were other “auteurs” who were responsible for many films, and Corliss got quite a boon by having the Old Man himself write the foreword to Talking Pictures, acknowledging and praising Corliss’s attempt to shift the attention of film buffs with this book.

|

| Lubitsch directs Garbo and Melvyn Douglas |

Talking Pictures is thus an argument against the director-as-auteur, but not the auteur theory per se. In the intro, the terms are defined this way:

“William Wyler was absolutely right to hold the director responsible for ‘a picture's quality’ — just as a conductor is responsible for the composer's symphony, or a contractor for the architect's plans. But he must also be responsible to something: the screenplay. With it, he can do one of three things: ruin it, shoot it, or improve it.” [p. 20]

Picking the scripter as the prime shaper of a movie seems like a sound decision until one actually factors in a few other items that aren’t usually the case with a director. The first, most important, is the profusion of scripters who worked on films during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Many of the movies from that era would have a person listed who concocted the storyline, then another set of writers who wrote the initial draft of the script, and then a final set, usually a duo, who “signed” the film as the main scripters.

In line with that, while it’s possible that an editor (or a heavy-handed producer of the Harvey Weinstein sort) could shift around a director’s work, it’s far more common that a scripter would toil on a film and then see his/her work completely scrapped by the next “set of hands.” Thus, in Talking Pictures, Corliss often has to play detective to attribute a given film to a given scripter. In some cases, he decides on discussing certain films as the work of certain lesser-remembered scripters (Charles Brackett, for instance), rather than their famous collaborators (Billy Wilder, in Brackett’s case).

The most striking thing about the book is that Corliss wrote it when he was a “young turk” in the film-crit biz, and thus he was not afraid to take swipes at certain revered figures. Thus, the man who in later years was considered quite a kind critic in his work for TIME (even when panning something, Richard could be uncommonly polite about slamming a talented person who had turned out a wretched movie) was quite ready in the early Seventies to dissect and tear down many movie classics.

I went on a spree a few years ago and wound up watching every film directed by Howard Hawks (not counting the missing silents, obviously, and the ones he was fired from or left). Thus I was surprised that one of the scripters responsible for some of Hawks' best works gets appraised/trashed by Corliss in Talking Pictures. The writer in question is Jules Furthman, whose screenplays during a four-and-a-half decade career, included The Docks of New York, Morocco, The Shanghai Express, and Blonde Venus (all Sternberg); Mutiny on the Bounty, Nightmare Alley; To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, Only Angels Have Wings, and Rio Bravo (the last quartet directed by Hawks; the final two being among the top tier of Golden Age films).

With that kind of pedigree you'd think Furthman might be in the first rank. He's actually in the third rank, and Corliss sums up his feelings about Furthman's writing this way:

“The problem is that there's not much difference between

best and worst Furthman. He is always competent, often compromising, rarely

compelling, and never incomparable. In general, Furthman exemplifies the kind

of screenwriter whose filmographic whole is greater than the sum of his

particular contributions to it, whose best work was done as the 'employee' of a

directing or performing personality stronger than his own, and whose career

deserves to be resurrected but not adored.” [p. 270]

So, in effect, the book is most interesting when Corliss takes on a contrarian position and trashes a writer whose films were pretty sublime (or was it Sternberg and Hawks who made those films sublime? Back to square one…). What RC makes clear at many points in the book is that he did read many of the screenplays in question, so he was also aware of many of the weaknesses inherent in Furthman's writing.

The odd thing, given the titles in question, is that the

films cited above are indeed quite, quite good — so to say that Furthman was

nothing better than a craftsman ends up becoming praise for his co-scripters

(including Faulkner on The Big Sleep), or an argument that

either Sternberg and Hawks were alchemists, making gold out of dross, OR the

studio system just turned out some heavy-duty classics amid the programmers and

routine vehicle pictures.

One last point of contention (mine, not Richard's): While Sarris arranged his book in “descending order” from his “pantheon” of great directors to “Subjects for Further Research.” Corliss on the other hand outlines his various strata in the book's introduction, and then groups the scripters thematically in the book proper so we don't start off or end up with the cream of the crop. The four categories he chose, incidentally, were “Parthenon” (not Pantheon!), Erechtheion, Propylaea, and “Outside the Walls.”

Last notes about the book itself: It closes out on a small group of scripters who had had great successes in the Sixties and Seventies. The positive write-ups here include his section on Carnal Knowledge and his entry for Robert Benton and David Newman. In the process of writing up the latter team, he reviews a script that was never made into a movie, “Hubba-Hubba.”

This is quite a ballsy move, and even more striking than the

fact that Sarris included projects in pre-production in the filmographies in

his book (for years, I've wondered why he put “Napoloeon” in Kubrick's listing,

given that the film hadn't even begun shooting). What I came to realize on

second reading of Talking Pictures is that Corliss might

have even suspected that “Hubba-Hubba” was dead in the water, and yet he

“reviewed” it in order to have an example of an unfilmed script.

He does mention in his rather lengthy entry (five pages, the same amount of space devoted to The Searchers) that the script features “three or four sequences that audiences will long remember — if they ever get to see them.” I could, of course, be completely wrong on this, given the fact that he also takes care to mention three projects written by Benton and Newman that were about to be filmed (one of them, he notes, should start filming by the time the book is published). None of the three ever saw the light of day….

The reason I'm doing this re-appraisal and resurrection of the book, though, is that it belongs to that period of time when movies really did matter to a greater number of people — given the present-day argument that “[A current excellent TV show] is just like cinema… in fact, it's our era's version of literature!” means that too many reviewers don't really like cinema all that much. (Very good TV is nothing to be sneezed at, but it is indeed just that — excellent TV. Not cinema, not literature, but very good television.)

In his best writing, Corliss went about this task as a critic in a very serious fashion. He also, like the good logic-based liberal he was, was very much open to debate. Books like The American Cinema and Talking Pictures were indeed intended to start arguments, but healthy arguments based on a real knowledge of the subject — rather than today's online “listicles” that declare certain things “worthy” of inclusion, with all else in the category being not even worth contemplation. (When you're making up a list of “films to see before you die,” you've already hit the rock-bottom Cliff Notes level of critical appraisal.)

Before I discuss the individuals whom Corliss clearly loved and hated, I should point to an instance in the book where he acknowledges that his opinions were open to debate:

“A truly dogmatic critic can talk himself into liking — or, at the very least, making a sophisticated case for — just about any film that appeals to his prejudices. So, although I continue to affirm my resistance to any formal theory that claims the screenwriter as an auteur, any reader deserves to be skeptical when I simply state that the pair of writer-director films, Darling Lili and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, can be recommended as more meaningful, more personal, and even, to the disinterested viewer, more satisfying than the offerings of our two Pantheon residents.” [p. 157]

I will discuss Corliss's dislikes before his likes, since he was always at his best when rhapsodizing about something he loved, and that is the best note to close on. I also do this because I tend to disagree with a few of his evaluations in this category, so I will be conducting a one-sided argument, which can only be answered by then giving Richard the final word, in the form of his praise for the writers whose work he truly did love.

His young turk attitude allows him at points to be brutally

frank about some much-beloved Hollywood personalities. A personal favorite of

mine is his tangential diss of two very exuberant blonde performers. While

discussing Norman Krasna, he takes time to single out “those paragons of

pointless energy, Debbie Reynolds and Sandra Dee.”

He goes on, in a somewhat caddish but (let’s be honest) uncannily accurate mode: “Both actresses were too tough to make it as Audrey Hepburns and too angular to be Marilyn Monroes; wide-eyed aggression would have to do. If that was enough to keep their careers afloat longer than their talents deserved, it also helped sink their movies. Debbie rarely transmitted a feeling of joy in her work; it was all work, reworking, and overworking.” [pp. 71-72]

Had he lived to see Reynolds’ departure, I'm sure he would've written a beautiful obit for her, studio-contracted object that she was, but in the Seventies he let it all hang out. Thus, we come to the places where he tears apart some of mine own faves. First, Frank Tashlin, who, he says found in the severe limitations of his leads (Jerry Lewis, Bob Hope, Red Skelton, Jack Carson, Lucille Ball) “exactly that quality of lumpy, proletarian inflexibility that would express his own view of comedy as submission to pain, and not — as the greatest silent comedy artists demonstrated — its sublime, effortless transcendence.” [p. 77]

So, in effect, the book is most interesting when Corliss takes on a contrarian position and trashes a writer whose films were pretty sublime (or was it Sternberg and Hawks who made those films sublime? Back to square one…). What RC makes clear at many points in the book is that he did read many of the screenplays in question, so he was also aware of many of the weaknesses inherent in Furthman's writing.

|

| Jules Furthman |

One last point of contention (mine, not Richard's): While Sarris arranged his book in “descending order” from his “pantheon” of great directors to “Subjects for Further Research.” Corliss on the other hand outlines his various strata in the book's introduction, and then groups the scripters thematically in the book proper so we don't start off or end up with the cream of the crop. The four categories he chose, incidentally, were “Parthenon” (not Pantheon!), Erechtheion, Propylaea, and “Outside the Walls.”

Last notes about the book itself: It closes out on a small group of scripters who had had great successes in the Sixties and Seventies. The positive write-ups here include his section on Carnal Knowledge and his entry for Robert Benton and David Newman. In the process of writing up the latter team, he reviews a script that was never made into a movie, “Hubba-Hubba.”

|

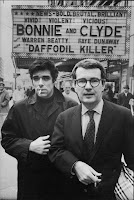

| Newman and Benton |

He does mention in his rather lengthy entry (five pages, the same amount of space devoted to The Searchers) that the script features “three or four sequences that audiences will long remember — if they ever get to see them.” I could, of course, be completely wrong on this, given the fact that he also takes care to mention three projects written by Benton and Newman that were about to be filmed (one of them, he notes, should start filming by the time the book is published). None of the three ever saw the light of day….

The reason I'm doing this re-appraisal and resurrection of the book, though, is that it belongs to that period of time when movies really did matter to a greater number of people — given the present-day argument that “[A current excellent TV show] is just like cinema… in fact, it's our era's version of literature!” means that too many reviewers don't really like cinema all that much. (Very good TV is nothing to be sneezed at, but it is indeed just that — excellent TV. Not cinema, not literature, but very good television.)

In his best writing, Corliss went about this task as a critic in a very serious fashion. He also, like the good logic-based liberal he was, was very much open to debate. Books like The American Cinema and Talking Pictures were indeed intended to start arguments, but healthy arguments based on a real knowledge of the subject — rather than today's online “listicles” that declare certain things “worthy” of inclusion, with all else in the category being not even worth contemplation. (When you're making up a list of “films to see before you die,” you've already hit the rock-bottom Cliff Notes level of critical appraisal.)

Before I discuss the individuals whom Corliss clearly loved and hated, I should point to an instance in the book where he acknowledges that his opinions were open to debate:

“A truly dogmatic critic can talk himself into liking — or, at the very least, making a sophisticated case for — just about any film that appeals to his prejudices. So, although I continue to affirm my resistance to any formal theory that claims the screenwriter as an auteur, any reader deserves to be skeptical when I simply state that the pair of writer-director films, Darling Lili and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, can be recommended as more meaningful, more personal, and even, to the disinterested viewer, more satisfying than the offerings of our two Pantheon residents.” [p. 157]

I will discuss Corliss's dislikes before his likes, since he was always at his best when rhapsodizing about something he loved, and that is the best note to close on. I also do this because I tend to disagree with a few of his evaluations in this category, so I will be conducting a one-sided argument, which can only be answered by then giving Richard the final word, in the form of his praise for the writers whose work he truly did love.

|

| Tammy and the Bachelor |

He goes on, in a somewhat caddish but (let’s be honest) uncannily accurate mode: “Both actresses were too tough to make it as Audrey Hepburns and too angular to be Marilyn Monroes; wide-eyed aggression would have to do. If that was enough to keep their careers afloat longer than their talents deserved, it also helped sink their movies. Debbie rarely transmitted a feeling of joy in her work; it was all work, reworking, and overworking.” [pp. 71-72]

Had he lived to see Reynolds’ departure, I'm sure he would've written a beautiful obit for her, studio-contracted object that she was, but in the Seventies he let it all hang out. Thus, we come to the places where he tears apart some of mine own faves. First, Frank Tashlin, who, he says found in the severe limitations of his leads (Jerry Lewis, Bob Hope, Red Skelton, Jack Carson, Lucille Ball) “exactly that quality of lumpy, proletarian inflexibility that would express his own view of comedy as submission to pain, and not — as the greatest silent comedy artists demonstrated — its sublime, effortless transcendence.” [p. 77]

|

| Jerry and Frank Tashlin |

One of the biggest turnabouts in Andrew Sarris's writing was that he openly condemned Billy Wilder in The American Cinema, placing him in the “Less Than Meets the Eye” category, but later realized Wilder was one of the greats whom he had been completely wrong about. I'm not certain what Richard's later take on Wilder was, but here he shares Sarris's Sixties contempt for the master-scripter [my phrase, not Corliss's] by expressing his loathing of the darker-than-dark A Foreign Affair (1948) as a “vile” film.

Also in the “hated it!” category, interestingly enough, is Abraham Polonsky's Force of Evil (1948), which is now commonly agreed upon as a masterpiece of both film noir and urban drama. Corliss finds it to be a triter creation by Polonsky, summing it up this way: “Like Odets and Fuchs, Polonsky was at his movie best when he thought he was selling out. When he was left on his own (as in Force of Evil and Willie Boy), the themes turned pedagogical, the images verged on the ponderous, the dialogue often surrendered epigrammatic cheekiness for muted soliloquies and voluptuous self-contempt.” [p. 136]

Corliss embraced some of the greatest visions of the Sixties maverick period. He wrote a review in 1968 praising the mostly-loathed Richard Lester downer Petulia (which is now thought of as a masterpiece, natch). His enthusiasm for the modernist filmmaking of that period did not, however, extend to Robert Altman's biggest hit, M*A*S*H (1970), which he hated.

His summation in his entry here on the film's screenwriter, Ring Lardner Jr. (who won an Oscar for his script, which had been greatly changed by Altman in the filming), was that its “characterizations lack the depth and consistency we demand when looking for a movie that's more than very funny. As with The Graduate, its tone is too distinct and erratic (The Hardy Boys one moment, Satan's Sadists the next) to fit it easily into a genre. And as with The Graduate, most critics tended to review a film they wanted to see instead of the film in front of them.” [p. 344] I disagree, but am thoroughly amused that RC got an Al Adamson reference into his pan.

The most intriguing thing about the final section of Talking Pictures is that Corliss chose to tackle the new Hollywood by singling out a group of screenwriters who sadly did not “rise” any further in the Seventies (unless you want to count Robert Benton, who became a successful director after splitting with his scripting partner Robert Newman). This chapter includes a thorough trashing of Funhouse hero Terry Southern, whom Corliss finds to be facile and none too witty (mine own feelings are in this piece).

The thing that hits one reading Talking Pictures from this later point in time is that there were scripters who became “superstars” in the years after the book came out. They usually became directors (like Paul Schrader), although some didn't (the enormously successful, and then utterly forgotten, Joe Eszterhas). In our correspondence he threw out a few names of people that he would've put into an updated version of the book, like Dustin Lance Black. While Woody Allen is another key name — since his films are mostly script and the visuals are really the creation of whoever is the cinematographer on that particular film — one of the most successful scripters-turned-directors was of course Francis Ford Coppola.

Moving on from those who were trashed to those who were treasured, we reach a film that is celebrated in Talking Pictures in two entries (the ones for Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer). Corliss states flat out that “His Girl Friday is Hawks's best comedy, and quite possibly his best film.” [p. 318]

This, the “most anarchic newspaper comedy of all time,”

inspires Corliss to one of his best insights about the films of Golden Age

Hollywood. He reflects on what movie viewers prize: “Though Walter bullies,

lies to, and spills things on Bruce, the film convinces us that Walter and

Hildy were made for each other, if only because angelic boredom is a greater

movie sin than stylish corruption.” [ibid]

One of the most interesting comparisons occurs when he's talking about Singin' in the Rain in his entry on Comden and Green. He notes that that perfect musical “suggests, without a wasted shot or twist of the plot, the same end of a sublime, ridiculous movie era that Billy Wilder painted, with broader, more delirious strokes, in Sunset Boulevard. The difference in tone is due as much to the two films' fidelity to their own themes as to the fact that Hagen is Singin' in the Rain's comic villainess, and not its tragic heroine." [p. 199]

One of the most interesting comparisons occurs when he's talking about Singin' in the Rain in his entry on Comden and Green. He notes that that perfect musical “suggests, without a wasted shot or twist of the plot, the same end of a sublime, ridiculous movie era that Billy Wilder painted, with broader, more delirious strokes, in Sunset Boulevard. The difference in tone is due as much to the two films' fidelity to their own themes as to the fact that Hagen is Singin' in the Rain's comic villainess, and not its tragic heroine." [p. 199]

|

| Trumbo |

“Of the self-destructive Mankiewicz, Ben Hecht wrote: ‘I knew that no one as witty and spontaneous as Herman would ever put himself on paper. A man whose genius is on tap like free beer seldom makes literature out of it.’ The art of conversation is not only a dying art, it is one that dies anew as the embers of a witty evening's memory turn to the dust of gossip.

“Mankiewicz ‘put himself on paper’ for the movies just once — when he wrote Citizen Kane. Trumbo's own genius was clandestine, conspiratorial, circulated only to special friends and formidable enemies. His screenplays deserve the oblivion most of them have already received; but his letters will live, for the true record of the man is there — in those florid, cantankerous, incandescent salvos.” [p. 262]

|

| Ben Hecht's first Oscar winner, dir. by Sternberg |

Or as RC puts it, “Hecht did offer a backhanded defense of the craft he loved and the restrictions he loathed. ‘It is as difficult to make a toilet seat as a castle window,’ he wrote in 1962, ‘even if the view is a bit different.’ During his long tenure in Hollywood, Ben Hecht made both. But at his best, he could make a porcelain privy glisten like stained glass on a sunny day.” [p. 24]

Corliss rhapsodizes about some less famous films as well, including scripter Norman Krasna’s Hands Across the Table (1935). Sure it’s a film directed by Lubitsch, but Richard raises the ante against Sarris by giving the screenwriters “authorship” of the film in this book. Of Hands, he notes (curiously praising Lubitsch more than Krasna) it “was Ernst Lubitsch's first film as Paramount's production chief. For once, the School of Lubitsch — which was attended, consciously or not, by most of Hollywood's best romantic-comedy writers and directors — produced a work eminently worthy of its master.” [p. 67]

|

| Letter From an Unknown Woman |

“Ophuls' woman-in-love theme achieves perhaps its most beautiful expression here; but the film reveals at least as many Kochian obsessions, most significantly the letter as a transmitter of intonations of love and intimations of death — a memento mori that can cleanse the receiver even as it kills the sender.” [p. 116]

And, while today’s cinephile reader might be surprised at the number of well-regarded scripters who come in for a beautifully worded drubbing in Talking Pictures, at other points the obvious talent of the masters is recognized and becomes the subject of lyrical prose.

|

| Sullivan's Travels |

"They were raffish, cynical small-timers in themselves, but when unified in opposition to the hero — which is what Sturges always did with them — they forgot their differences and banded into a powerful force for intimidation. Individually, they were bull throwers; collectively, they were a bulldozer. And it took the Sturgean hero a full ninety minutes to free himself, however tentatively, from their grasp.” [p. 45]

The modern (read: post-studio system) screenplay that comes in for the most praise in the book’s last chapter is Jules Feiffer’s script for Carnal Knowledge (1971). Corliss is unabashed in his praise of the script (and the film). One wishes there had been a Feiffer script that was in the same league after ’71 — I will steadfastly defend two-thirds of Altman’s Popeye (1980), but Resnais’ I Want to Go Home (1989) is a major disappointment, despite the references in the film to master cartoonists Will Eisner and Lee Falk.

When analyzing Carnal Knowledge, Corliss

does a fine job of contextualizing the many media that Feiffer was working in

at the turn of the Seventies: “Those who say Feiffer's vision is simplistic

because he is a cartoonist are wrong; it is simple because he is a moralist.

That vision is a creation unique in its comic pessimism. It is also remarkably

consistent, which may explain why Little Murders, conceived

as a novel, succeeded as a play — and why Carnal Knowledge,

conceived as a play, stands as the most personal and perceptive film to emerge

from the new breed of screenwriters.” [p. 366]

Like The American Cinema, Talking Pictures was sadly never updated and thus is forever frozen in amber at the beginning of the Seventies. It can be easily found in the usual places where secondhand books dwell and remains a remarkably well-written cause for arguments among movie buffs who care about and love old Hollywood. (It made perfect that the last institution to embrace Corliss was the stalwart destination for all of us smitten with old movies, Turner Classic Movies.)

Richard had other loves in the world of cinema — and many in the other arts, from theater and literature to music, erotica, and comic books — which I hope to chronicle in future blog entries. His writing was filled with enthusiasm for the things that he loved, and while Talking Pictures reveals an earlier, surprisingly acerbic Corliss, his best reviews and theme pieces (a lot of them done for the Internet in this century) deserve to be read in the decades to come. Any publishers (or academic presses) up for a collection of RC’s best and most eclectic writing?

*****

And since the man himself enjoyed diversions, tangents, and connecting the dots with trivia, I have to note that while I wrote this piece over the last several weeks I kept hearing this song in my head.

Like The American Cinema, Talking Pictures was sadly never updated and thus is forever frozen in amber at the beginning of the Seventies. It can be easily found in the usual places where secondhand books dwell and remains a remarkably well-written cause for arguments among movie buffs who care about and love old Hollywood. (It made perfect that the last institution to embrace Corliss was the stalwart destination for all of us smitten with old movies, Turner Classic Movies.)

Richard had other loves in the world of cinema — and many in the other arts, from theater and literature to music, erotica, and comic books — which I hope to chronicle in future blog entries. His writing was filled with enthusiasm for the things that he loved, and while Talking Pictures reveals an earlier, surprisingly acerbic Corliss, his best reviews and theme pieces (a lot of them done for the Internet in this century) deserve to be read in the decades to come. Any publishers (or academic presses) up for a collection of RC’s best and most eclectic writing?

*****

And since the man himself enjoyed diversions, tangents, and connecting the dots with trivia, I have to note that while I wrote this piece over the last several weeks I kept hearing this song in my head.