When

I talk about Jerry Lewis on the Funhouse TV show, I’ve often noted

that his comedy films (particularly the imaginative, charming ones he

made with director Frank Tashlin) will be able to be more fully

appreciated when Jerry has passed on. Even though he has been

mellowing in recent years — and many members of the public who

never liked him were saddened by him being booted from the telethon —

Jerry’s abrasive attitude in public has served as the biggest

obstacle to his comedy work being appreciated.

The same is true of Lou Reed. Now that he has left this mortal coil, he is no longer around to be rude to interviewers, so what is left is his truest legacy: his music (and yes, those pieces by Bangs I explored in the second part of this piece will live on forever, but those are also about Lester’s worship of Lou’s best music).

The same is true of Lou Reed. Now that he has left this mortal coil, he is no longer around to be rude to interviewers, so what is left is his truest legacy: his music (and yes, those pieces by Bangs I explored in the second part of this piece will live on forever, but those are also about Lester’s worship of Lou’s best music).

We

can now explore the 22 studio albums he put out — plus the legally

released live albums, which range from the best (Rock ‘n’

Roll Animal) to later experimental items with the “Metal

Machine Trio” (not counting the literally hundreds of live bootlegs

on the Net) to absolute crap (Take No Prisoners) —

without having to think of Lou's abrasive interludes.

Now onto the Reed solo-career discography, without “lettered” grades, since we know how much Lou hated Christgau’s rating system (wonder what he thought of Entertainment Weekly's appropriation thereof).

First, I should suggest if you’re intrigued by any of this stuff, or just want to hear any one of *dozens* of Reed bootlegs, check out the YT accounts of a RABID Lou fan, who says he’s posting items given to him by a super-fan named “Lyoko.” His two accounts are here and here; his postings are comprised of 21 of the legally released albums and literally countless full concerts from the Seventies through the 2000s.

Since the Net contains too many fucking Top 10 lists already, I will include one and only one in this piece. My top tier of Lou albums would be these 10 (ordered chronologically):

Now onto the Reed solo-career discography, without “lettered” grades, since we know how much Lou hated Christgau’s rating system (wonder what he thought of Entertainment Weekly's appropriation thereof).

First, I should suggest if you’re intrigued by any of this stuff, or just want to hear any one of *dozens* of Reed bootlegs, check out the YT accounts of a RABID Lou fan, who says he’s posting items given to him by a super-fan named “Lyoko.” His two accounts are here and here; his postings are comprised of 21 of the legally released albums and literally countless full concerts from the Seventies through the 2000s.

Since the Net contains too many fucking Top 10 lists already, I will include one and only one in this piece. My top tier of Lou albums would be these 10 (ordered chronologically):

1-4.)

The Velvet Underground albums (available together as the CD box set

Peel Slowly and See)

5.)

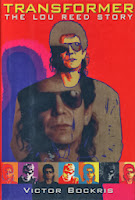

Transformer

6.)

Berlin

7.)

The Blue Mask (the harder, angst-ridden songs)

8.)

New

York

9.)

Songs

for Drella

10.)

Magic

and Loss

And, to a lesser degree, his eponymous first solo LP from ’72, Sally Can't Dance and the tongue-in-cheek LP that is Coney Island Baby. Metal Machine Music is up near the top tier simply because it is aggressive and insane, thus worthy of a mind-fuck or two.

I’ll close out this obit with a discussion of the last three items on that list, but first I want to explore the “middle-period” Reed, which contains a handful of great songs and some LPs that are just heinously lame:

And, to a lesser degree, his eponymous first solo LP from ’72, Sally Can't Dance and the tongue-in-cheek LP that is Coney Island Baby. Metal Machine Music is up near the top tier simply because it is aggressive and insane, thus worthy of a mind-fuck or two.

I’ll close out this obit with a discussion of the last three items on that list, but first I want to explore the “middle-period” Reed, which contains a handful of great songs and some LPs that are just heinously lame:

The

“Arista Years”:

Rock

and Roll Heart ('76): the title tune is all that you need

to hear from this directionless “interim” album.

Street

Hassle ('78): the title tune and “We're Gonna Have a Real

Good Time” (which Patti Smith covered wonderfully in concert) are

the sole standouts.

The

Bells: not one good tune on the fucking disk. “Disco

Mystic” is particularly abominable, time you won’t be getting

back.

Growing

Up in Public ('80): Lou confronts his alcoholism for the

first time on this album, with a startlingly unflattering photo on

the cover (he looked much worse for the wear at only 38 years of

age). He complains about his parents, preaches that we should “Teach

the Gifted Children,” and in one song rhymes “Escher” with

“Measure for Measure.” The sole virtue is his tongue-in-cheek ode

to booze, “Power of Positive Drinking.”

In 1982, Lou returned to RCA and put out his first truly powerful album since Berlin, The Blue Mask. In relistening to it to write this piece, I realized that the record is half-masterpiece/half-Arista-level material. The worst item is definitely “Heavenly Arms” (the aforementioned Lou-bellowing-about-Sylvia song I referred to in the first paragraph of the first part of this entry). It's goddamned dreadful.

In 1982, Lou returned to RCA and put out his first truly powerful album since Berlin, The Blue Mask. In relistening to it to write this piece, I realized that the record is half-masterpiece/half-Arista-level material. The worst item is definitely “Heavenly Arms” (the aforementioned Lou-bellowing-about-Sylvia song I referred to in the first paragraph of the first part of this entry). It's goddamned dreadful.

On

the other hand, the album contains four songs that are back in the

traumatic groove that Lou pioneered with the Velvet Underground.

“Underneath the Bottle” and “The Gun” are disturbing numbers

that sketch a man on the edge; “The Blue Mask” and “Waves of

Fear” are on a level with the finest VU work.

The strength of these songs comes no doubt from the fact that Lou was in the midst of cleaning up after years of booze and drugs when he wrote them; they also benefit from a stripped-down approach – just Lou performing with Fernando Saunders (bass), Doane Perry (drums), and the amazing Robert Quine on guitar. One thing is certain: they are closest that rock has come to approximating the work of the brilliant novelist Hubert Selby.

“Waves of Fear” is delirium tremens in musical form: “Crazy with sweat, spittle on my jaw/what's that funny noise, what's that on the floor/Waves of fear, pulsing with death/I curse my tremors, I jump at my own step/I cringe at my terror, I hate my own smell/I know where I must be, I must be in hell.”

The strength of these songs comes no doubt from the fact that Lou was in the midst of cleaning up after years of booze and drugs when he wrote them; they also benefit from a stripped-down approach – just Lou performing with Fernando Saunders (bass), Doane Perry (drums), and the amazing Robert Quine on guitar. One thing is certain: they are closest that rock has come to approximating the work of the brilliant novelist Hubert Selby.

“Waves of Fear” is delirium tremens in musical form: “Crazy with sweat, spittle on my jaw/what's that funny noise, what's that on the floor/Waves of fear, pulsing with death/I curse my tremors, I jump at my own step/I cringe at my terror, I hate my own smell/I know where I must be, I must be in hell.”

“Blue

Mask” is a masochistic anthem, a lyric that reeks of self-loathing

and pain worship: “Make the sacrifice/mutilate my face/If you need

someone to kill/I'm a man without a will/Wash the razor in the

rain/let me luxuriate in pain/Please don't set me free/death means a

lot to me.” (I'll take bets a young Mr. Reznor was listening.)

That

was basically it for Lou's Selby-like trip. On his next LP he went

full-throttle into the biker/tough-guy pose he kept up for most of

the Eighties. Legendary Hearts ('83) is a mostly

forgettable album, that includes one more fatalistic addiction ode

(“The Last Shot”), and Lou putting us on notice that he's happy and

doing well financially (“Rooftop Garden”).

New

Sensations ('84) spawned the song “I Love You, Suzanne”

that broke Lou on MTV (see part 3 of this blog entry). At this point he's still in

transition (Lou's transition lasted more than a decade and a half),

still trying to find the right vocal style for his lyrics.

New

Sensations ('84) spawned the song “I Love You, Suzanne”

that broke Lou on MTV (see part 3 of this blog entry). At this point he's still in

transition (Lou's transition lasted more than a decade and a half),

still trying to find the right vocal style for his lyrics.The most-indulgent, yet enjoyably nostalgic, song on the record is “Doin' the Things That We Want to,” a “where-did-this-come-from?” tribute to the works of Sam Shepherd and Martin Scorsese, in which he considers both men colleagues (the song is lively and sounds like a plea from Lou for collaboration with either or both of them).

In

1987, Lou tried to inject a “danceable” note to his music in the

album Mistrial. “Video Violence” and “The

Original Wrapper” show Reed trying to be audience-friendly and

retain his new MTV following. He also executed a sort of dry run for

the New York album with the topical lyrics of

“Video Violence.” The slower songs were still a drag, however.

****

It's

impossible to call the 1989 New York album by Reed

a “comeback,” since he had never gone away, but it most certainly

was a return to form, and the first completely excellent album from

start to finish since Berlin. Working at the

height of his powers here, Lou turned out a “newspaper” album,

the kind of thing that Phil Ochs did in '64 (All the News

That's Fit to Sing) and Lennon took a stab at in '72 with

Some in New York City.

What

Lou wound up delivering was the rock equivalent of Bonfire

of the Vanities, a time capsule that is filled with

beautifully sketched portraits of big city life and political issues

in the late Eighties, with the references unrepentantly dated and

localized to New York City.

Some of the self-righteous anger (especially in “Good Morning Mr. Waldheim”) doesn't make for the best rock “poetry” – in fact, it's clunky as hell – but New York is the first album where Reed perfectly matched his limited vocal range to the melodies.

He also crafted a “character” that suited him, a cranky chronicler of a city (and civilization) in decline that is touted as being on the “upswing” (Guiliani is one of the many real-life figures who are namechecked and/or mocked on the album). The clear, pure sound of one of Reed's idols, Dion, counterpointed with Lou's own sardonic, nasal narration, make “Dirty Boulevard” unforgettable on both a musical and “storytelling” level.

Some of the self-righteous anger (especially in “Good Morning Mr. Waldheim”) doesn't make for the best rock “poetry” – in fact, it's clunky as hell – but New York is the first album where Reed perfectly matched his limited vocal range to the melodies.

He also crafted a “character” that suited him, a cranky chronicler of a city (and civilization) in decline that is touted as being on the “upswing” (Guiliani is one of the many real-life figures who are namechecked and/or mocked on the album). The clear, pure sound of one of Reed's idols, Dion, counterpointed with Lou's own sardonic, nasal narration, make “Dirty Boulevard” unforgettable on both a musical and “storytelling” level.

Reed

followed the New York album with Songs

for Drella ('90), a suite of songs he cowrote and performed

with John Cale in tribute to Andy Warhol. This is the album that

would've most likely made the best Lou Reed off-Broadway show, since

(aside from Lou's fervent “I Believe,” about his wishes that they

had killed Valerie Solanas for shooting his hero Andy) the songs are

primarily written from the perspective of a single character (Andy)

and the stripped-down sound created by Lou on guitar and Cale on

piano and violin is both economical and powerful as hell.

In the album, Reed and Cale alternate vocals, with Cale assuming the quiet, public side of Warhol and Lou incarnating his professional and conceptual side (plus the anger that he never seemed to have expressed). The fact that the two were back together again, making music for the first time since 1967, was amazing, and the resulting show/album was nothing short of brilliant – Lou had to up his game when Cale was around (the Welsh one being a schooled musician who dwelt in the real avant-garde before the VU; Lou basically had to create his own little “wing” of the underground).

In the album, Reed and Cale alternate vocals, with Cale assuming the quiet, public side of Warhol and Lou incarnating his professional and conceptual side (plus the anger that he never seemed to have expressed). The fact that the two were back together again, making music for the first time since 1967, was amazing, and the resulting show/album was nothing short of brilliant – Lou had to up his game when Cale was around (the Welsh one being a schooled musician who dwelt in the real avant-garde before the VU; Lou basically had to create his own little “wing” of the underground).

The

back-and-forth between their instruments (as on the VU live reunion

album) makes the music crackle, and the best songs – the sarcastic

“Small Town” or the elegaic “Forever Changed” – are what

the VU might've sounded like if either of these gents could've stood

each other's company for a longer period of time.

And, although Cale was very generous to Lou in the program notes for the show (saying it was mostly Lou's show and he was only a singer/performer), it was essential that there be another voice in the project – Lou could not have carried off the song “The Trouble with Classicists” the way that Cale did.

And, although Cale was very generous to Lou in the program notes for the show (saying it was mostly Lou's show and he was only a singer/performer), it was essential that there be another voice in the project – Lou could not have carried off the song “The Trouble with Classicists” the way that Cale did.

I

saw the live performance of the songs at the Brooklyn Academy of

Music and was struck by the use of slides on a big screen behind Reed

and Cale. The effect of augmenting the music with Warhol's paintings

from the era and photographs of the people and locations was

overwhelming. I remember being very disappointed upon purchasing the

1990 VHS version of the show (directed by the great Ed Lachman) to

see that the images of Warhol's paintings weren't in the shots.

The VHS version can be seen in piecemeal fashion on YT, but still what you see are the two men playing and singing, not the stuff that was going on above them on the screen, as here in the song that best used the Warhol images, called (fittingly enough), “Images”:

The VHS version can be seen in piecemeal fashion on YT, but still what you see are the two men playing and singing, not the stuff that was going on above them on the screen, as here in the song that best used the Warhol images, called (fittingly enough), “Images”:

Lou’s

last great achievement was Magic and Loss, his '92

album about dealing with the death of a friend (Reed said in

interviews that it was inspired by the deaths of two friends of his,

one of whom was famed songwriter Doc Pomus). The album continues on

from Songs for Drella, with Lou exploring the

topic from several angles, from visiting the friend in the hospital

to disposing of their ashes and, most touching, dreaming about the

person after their death.

Too

often Lou surrendered to his pet emotions — anger and angst — in

his songwriting, but here he adopts an adult attitude throughout,

balancing the sadness of loss with the joy of having loved a friend

(and knowing how much they’d scoff at the somber nature of their

memorial service).

Magic and Loss is not as eminently re-listenable a record as his best rock albums because it so sad at points, but it does place Lou in the category of the great singer/songwriters, who crafted a musical identity for themselves while delivering sober truths in song. It’s also, needless to say, an incredibly “middle-aged” album, as it deals with one of the most common situations we encounter after age 40. And one of middle age’s most common emotions: regret.

There are things we say we wish we knew and in fact we never do

but I'd wish I'd known that you were going to die

Then I wouldn't feel so stupid, such a fool that I didn't call

and I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

No there's no logic to this - who's picked to stay or go

if you think too hard it only makes you mad

But your optimism made me think you really had it beat

so I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

No - I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

And if the beautifully elegiac tunes don’t do it for you, there’s also an extremely Selby-esque “short story” called “Harry’s Crucifixion” that finds Lou back in “Blue Mask” mode, although in a quiet, calmer fashion and with a Freudian “back story” this time….

Magic and Loss is not as eminently re-listenable a record as his best rock albums because it so sad at points, but it does place Lou in the category of the great singer/songwriters, who crafted a musical identity for themselves while delivering sober truths in song. It’s also, needless to say, an incredibly “middle-aged” album, as it deals with one of the most common situations we encounter after age 40. And one of middle age’s most common emotions: regret.

There are things we say we wish we knew and in fact we never do

but I'd wish I'd known that you were going to die

Then I wouldn't feel so stupid, such a fool that I didn't call

and I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

No there's no logic to this - who's picked to stay or go

if you think too hard it only makes you mad

But your optimism made me think you really had it beat

so I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

No - I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

I didn't get a chance to say goodbye

And if the beautifully elegiac tunes don’t do it for you, there’s also an extremely Selby-esque “short story” called “Harry’s Crucifixion” that finds Lou back in “Blue Mask” mode, although in a quiet, calmer fashion and with a Freudian “back story” this time….

******

The single best way to end this long-assed tribute to Lou Reed is to highlight the one song I’ve played more than ANY other Reed-related item (in fact I used it as the theme to the Funhouse for a very short while many years ago). It appears on the Velvet Underground rarities album Another View (’86), and I’ve found it’s one of those indisputably upbeat, hard-driving numbers that will jumpstart me in even the lowest of moods.

The VU with Cale in Dec. ’67 doing the instrumental version of “Guess I’m Falling in Love.”

The single best way to end this long-assed tribute to Lou Reed is to highlight the one song I’ve played more than ANY other Reed-related item (in fact I used it as the theme to the Funhouse for a very short while many years ago). It appears on the Velvet Underground rarities album Another View (’86), and I’ve found it’s one of those indisputably upbeat, hard-driving numbers that will jumpstart me in even the lowest of moods.

The VU with Cale in Dec. ’67 doing the instrumental version of “Guess I’m Falling in Love.”

Goodbye,

Lou, you hard-rockin’ pain in the ass!