First let’s talk about Lester. Lester Bangs was an incredibly talented writer who wound up being a rock critic. His articles still shine with insight, brilliant turns of phrase, and wonderfully weird notions decades after he wrote them — and the records he was talking about have in many cases disappeared (I know somebody’s gotta be out there listening to the Godz, but I’ve yet to meet them).

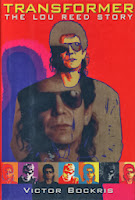

I

mentioned in the first part of this piece that Lou Reed was a

musician’s musician whose mythos was created by journalists.

Inarguably, David Bowie was the most important friend Lou ever made

in the music business. The Velvet Underground had a helluva solid

critical reputation but never sold records; when Bowie produced

Transformer for Lou (at the peak of his Ziggy

fame), suddenly Lou Reed had a record on the charts, with “Walk on the

Wild Side” instantly becoming his theme song.

Bowie was the most important fan that Lou ever had (he first professed his love for the music on Hunky Dory), but Lester Bangs was the most vociferous, the most dedicated — it’s noted in Jim DeRogatis’ Bangs-bio Let It Blurt that, even after Lester swore he wouldn’t ever write about Lou again, Cynthia Heimel (who dated Lester for a short time) noted, “He did not realize he could talk for sixteen hours about 'Lou Reed, Lou Reed, Lou Reed, Lou Reed!' “

Bowie was the most important fan that Lou ever had (he first professed his love for the music on Hunky Dory), but Lester Bangs was the most vociferous, the most dedicated — it’s noted in Jim DeRogatis’ Bangs-bio Let It Blurt that, even after Lester swore he wouldn’t ever write about Lou again, Cynthia Heimel (who dated Lester for a short time) noted, “He did not realize he could talk for sixteen hours about 'Lou Reed, Lou Reed, Lou Reed, Lou Reed!' “

Bangs

(seen at right) proselytized about Reed, so when he had a problem with Lou’s music

— mostly when his songwriting was getting too facile, or his public

image was becoming that of a scrawny glam clown — it mattered and

made sense, because Lester felt that Lou was an immense talent who

should have become the singer-songwriter of the

Seventies. (You must remember that one of Lester’s most memorable

pieces is called “James Taylor Marked for Death.”)

Reading Bangs’ writing made me a diehard Lou fan. The incredibly vibrant and enthusiastic way that Lester wrote about the VU and solo Reed, the sheer intensity of it, has been unmatched in modern writing about rock — except, of course, for the way that Lester wrote about the Stooges, Van Morrison, and a few others.

Reading Bangs’ writing made me a diehard Lou fan. The incredibly vibrant and enthusiastic way that Lester wrote about the VU and solo Reed, the sheer intensity of it, has been unmatched in modern writing about rock — except, of course, for the way that Lester wrote about the Stooges, Van Morrison, and a few others.

Yes,

reading Lester converted me to a Lou Reed fan (the two are seen at left with Patti Smith between them). I previously had

two VU LPs and Transformer, but after reading

Bangs’ raves and rants about Lou I wanted to hear the body of work,

and so I did (comments on the “forgotten” solo albums in the last installment).

Lester served as Lou’s “conscience,” questioning him about topics relating to his music and his persona. As I noted in the first part of this piece, Lou never tolerated questions that didn’t directly relate to whatever he was flogging at the moment, so Lester’s interviews with him (or, more properly, mutual scream sessions) were indeed extraordinary.

Lester served as Lou’s “conscience,” questioning him about topics relating to his music and his persona. As I noted in the first part of this piece, Lou never tolerated questions that didn’t directly relate to whatever he was flogging at the moment, so Lester’s interviews with him (or, more properly, mutual scream sessions) were indeed extraordinary.

Lou

found it fun to “joust” with Lester, put him down verbally, and

let him go to places that no other journalist was ever allowed. But

Bangs got the final laugh, since the pieces he wrote were often

better than the albums Lou was making at the time.

The first full-length interview Lester had with Lou, titled “Lou Reed: Deaf Mute in a Phone Booth” (Nov. 1973) is up in its entirety on The Guardian website. In it we see Lou confronted by his hero at his worst: “His face has a nursing-home pallor, and the fat girdles his sides. He drinks double Johnnie Walker Blacks all afternoon, his hands shake constantly and when he lifts his glass to drink he has to bend his head as though he couldn't possibly get it to his mouth otherwise.”

The conversation eventually degenerates into a very entertaining shouting match (wherein at one point Lester yells at Lou, “Why doncha write a song like ‘Sugar, Sugar’? That'd be something worthwhile!”). But before it does, Lou actually does get “the question” in about alternative lifestyles that the later, calmer, Tai-chi-practicing Lou refused to go near.

The first full-length interview Lester had with Lou, titled “Lou Reed: Deaf Mute in a Phone Booth” (Nov. 1973) is up in its entirety on The Guardian website. In it we see Lou confronted by his hero at his worst: “His face has a nursing-home pallor, and the fat girdles his sides. He drinks double Johnnie Walker Blacks all afternoon, his hands shake constantly and when he lifts his glass to drink he has to bend his head as though he couldn't possibly get it to his mouth otherwise.”

The conversation eventually degenerates into a very entertaining shouting match (wherein at one point Lester yells at Lou, “Why doncha write a song like ‘Sugar, Sugar’? That'd be something worthwhile!”). But before it does, Lou actually does get “the question” in about alternative lifestyles that the later, calmer, Tai-chi-practicing Lou refused to go near.

Namely,

was Lou’s music and appearance touting the gay lifestyle? Sez Lou

in the piece “…You can't fake being gay, because being gay

means you're going to have to suck cock, or get fucked. I think

there's a very basic thing in a guy if he's straight where he's just

going to say no: 'I'll act gay, I'll do this and I'll do that, but I

can't do that.'

"I could say something like if in any way my album helps people decide who or what they are, then I will feel I have accomplished something in my life. But I don't feel that way at all. I don't think an album's gonna do anything. You can't listen to a record and say, 'Oh that really turned me onto gay life, I'm gonna be gay.' … By the time a kid reaches puberty they've been determined. Guys walking around in makeup is just fun. Why shouldn't men be able to put on makeup and have fun like women have?"

"I could say something like if in any way my album helps people decide who or what they are, then I will feel I have accomplished something in my life. But I don't feel that way at all. I don't think an album's gonna do anything. You can't listen to a record and say, 'Oh that really turned me onto gay life, I'm gonna be gay.' … By the time a kid reaches puberty they've been determined. Guys walking around in makeup is just fun. Why shouldn't men be able to put on makeup and have fun like women have?"

Lester’s

further meditations on Lou’s statement (again, read the article, for the full thing) are also fascinating and spot-on: “If

Lou Reed seems like rock's ultimate closet queen by virtue of the

fact that he came out of the closet and

then went back in,

it must also be observed that lots of people, especially lots of gay

people, think Lou Reed's just a heterosexual onlooker exploiting gay

culture for his own ends.…

“But let's just suppose that Lou Reed is gay. If he is, can you imagine what kind of homosexual would say something like that? Maybe that's what makes him such a master of pop song – he's got such a great sense of shame. Either that or the ultimate proof of his absolute normality is the total offensive triteness of his bannered Abnormality. Like there's no trip cornier'n S&M, every move is plotted in advance from a rigid rulebook centuries old, so every libertine ends up yawning his balls off.”

“But let's just suppose that Lou Reed is gay. If he is, can you imagine what kind of homosexual would say something like that? Maybe that's what makes him such a master of pop song – he's got such a great sense of shame. Either that or the ultimate proof of his absolute normality is the total offensive triteness of his bannered Abnormality. Like there's no trip cornier'n S&M, every move is plotted in advance from a rigid rulebook centuries old, so every libertine ends up yawning his balls off.”

The

“second round” between Lester and Lou can be found in the article

“Let Us Now Praise Famous Death Dwarves,” which is collected in

the utterly essential book Psychotic Reactions and

Carburetor Dung edited by Greil Marcus (Knopf, 1987). In

that encounter, Lester and Lou once again turn the classic rock

musician/fan-interviewer model on its head by at first sizing each

other up and then hollering (spot-on) insults at each other.

At this point Lou was fully entrenched in his glam persona — the height of which saw him thin as a stick (from speed), sporting dyed blonde hair and nail polish, endlessly posing for a photographer who might or might not be there (the very vision of a faded Warhol superstar, but this was when Lou’s records were selling!).

Again, Lester gets some interesting quotes out of Lou, and the two wind up yelling (incredibly accurate) insults at each other. Lester’s remarks about Lou having become a “self-parody” who delivers “pasteurized decadence” are true (but then again, the band he was traveling with was great at that time — the Hunter-Wagner group of Berlin and Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal fame, so the music he was making onstage was his best-ever, in the minds of many diehard fans).

At this point Lou was fully entrenched in his glam persona — the height of which saw him thin as a stick (from speed), sporting dyed blonde hair and nail polish, endlessly posing for a photographer who might or might not be there (the very vision of a faded Warhol superstar, but this was when Lou’s records were selling!).

Again, Lester gets some interesting quotes out of Lou, and the two wind up yelling (incredibly accurate) insults at each other. Lester’s remarks about Lou having become a “self-parody” who delivers “pasteurized decadence” are true (but then again, the band he was traveling with was great at that time — the Hunter-Wagner group of Berlin and Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal fame, so the music he was making onstage was his best-ever, in the minds of many diehard fans).

Only

a true fan of an artist could sum up his hero in such a laser-sharp

manner: (pp. 170-171) “Lou is the guy who gave dignity and poetry

and rock ‘n’ roll to smack, speed, homosexuality, sadomasochism,

murder, misogyny, stumblebum passivity, and suicide, and

then proceeded to belie all his achievements and return to the mire

by turning the whole thing into a monumental bad joke with himself as

the woozily insistent Henny Youngman in the center ring, mumbling

punch lines that kept losing their punch.”

(p. 172) “… Lou realized the implicit absurdity of the rock ‘n’ roll bête-noire badass pose and parodied, deglamorized it. Thought that may be giving him too much credit. Most probably he had no idea what he was doing, which was half the mystique. Anyway, he made a great bozo, a sort of Eric Burdon of sleaze.”

(p. 172) “… Lou realized the implicit absurdity of the rock ‘n’ roll bête-noire badass pose and parodied, deglamorized it. Thought that may be giving him too much credit. Most probably he had no idea what he was doing, which was half the mystique. Anyway, he made a great bozo, a sort of Eric Burdon of sleaze.”

Bangs

continued to write about Lou — until he finally felt he’d

overdone his Lou-worship in print and swore never to write him again

(but still did, more below). The most amusing writing he ever did

about Mr. Reed was most certainly his slew of articles about Metal

Machine Music, the 1975 feedback-noise album that was

either Lou’s giant “fuck you” to his record company, or a

complicated, dense piece of experimental work.

Lester wrote not one but two articles that were nothing but lists of things he had thought about the record (the finisher, the K.O., was him declaring “It is the greatest record ever made in the history of the human eardrum. Number Two: KISS Alive!”). These articles can be found in Psychotic Reactions, and its follow-up Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste (Anchor Books, 2003); the first piece is also available online here (for some reason lacking the numbers Lester employed in his original; the article is intended as a numerical list). At one point, he rejoices in the fact that, whatever its starting point, MMM is an emotional work:

Lester wrote not one but two articles that were nothing but lists of things he had thought about the record (the finisher, the K.O., was him declaring “It is the greatest record ever made in the history of the human eardrum. Number Two: KISS Alive!”). These articles can be found in Psychotic Reactions, and its follow-up Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste (Anchor Books, 2003); the first piece is also available online here (for some reason lacking the numbers Lester employed in his original; the article is intended as a numerical list). At one point, he rejoices in the fact that, whatever its starting point, MMM is an emotional work:

(p.

196) “… Besides which, any record that sends listeners fleeing

the room screaming for surcease of aural flagellation or,

alternately, getting physical and disturbing your medication to the

point of breaking the damn thing, can hardly be accused, at

least in results if not original creative man-hours, of lacking

emotional content.”

If you want to read what Lou said about the album in recent years — he definitely was sticking to the “dense piece of experimental work” explanation — you can find an interesting interview with him here.

If you want to read what Lou said about the album in recent years — he definitely was sticking to the “dense piece of experimental work” explanation — you can find an interesting interview with him here.

But,

once again, Lester hit the mark by recounting in Creem

(Feb. '76) a remark Lou made to Funhouse interview subject and

favorite Howard Kaylan: “Well, anybody who gets to side four is

dumber than I am.” While it’s entirely still possible to enjoy

MMM as Lester did and I have, as a sonic

“cleanser” — the feedback noises Lou created do do much to play

with your mind, if heard on headphones— and it is

a damned rebellious move by a guy whose previous LP (Sally

Can’t Dance) had been Bowie-less but still sold very

well, it’s interesting to know what he said about it behind closed

doors….

One

thing’s for sure: like any devoted fan, Lester dreamed of being

able to influence his hero to do his best, and in his writing it

often seemed like he was having a conversation with Lou. This

is nowhere more apparent than in two previously unseen fragments

from 1980 that were first published in Psychotic

Reactions. Lester was a marvelously talented writer whose

style was copied by most every music critic that followed (whether

they knew it or not). But what did he write about when he was writing

for himself?

(p. 168) “Aw, Lou, it’s the best music ever made, the instrumental intro to ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ is like watching dawn break over a bank of buildings through the windows of those elegantly hermetic cages, which feels too well spoken, which I suspect is the other knife that cuts through your guts, the continents that divide literature and music and don’t care about either.”

(p. 168) “Aw, Lou, it’s the best music ever made, the instrumental intro to ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ is like watching dawn break over a bank of buildings through the windows of those elegantly hermetic cages, which feels too well spoken, which I suspect is the other knife that cuts through your guts, the continents that divide literature and music and don’t care about either.”

(p.

201) “The real question is what to live for. And I can’t answer

it. Except another one of your records. And another chance for me to

write. Art for art’s sake, corny as that. And I bet Andy believes

it too. Otherwise he woulda killed himself a long time ago.”

In the next two parts of this tribute, I will finally tackle Lou's music, spotlighting the worst and the very best of his (legal) output. If you want to see a great collection of Lou posin' for the camera, visit the "Fuck Yeah Lou Reed" Tumblr.

In the next two parts of this tribute, I will finally tackle Lou's music, spotlighting the worst and the very best of his (legal) output. If you want to see a great collection of Lou posin' for the camera, visit the "Fuck Yeah Lou Reed" Tumblr.