|

| Aldrich, holding the French "bible" of film noir, Panorama du Film Noir Americain. |

That depiction was so far from the truth of the matter and was such a disservice to Aldrich that I wanted to put his real achievement in focus once again — and the only way to do that is rewatch his films (and give a first viewing to the lesser-known titles).

First, since everything on the Net is now done in “listicle” form, I will briefly run through the good and bad aspects of the miniseries in that misbegotten but much-beloved short-attention-span format. First, the positive aspects:

— The cast was filled with uncommonly talented performers;

— the two leads both did great jobs incarnating their legendary characters (albeit on very different levels of performance);

— and despite occasional jarring, small anachronisms, the show's focus on the artifacts of its era was impressive.

|

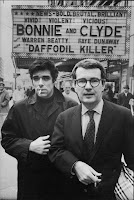

| Robert Aldrich, Alfred Molina in Aldrich garb. |

— The two leads were on different wavelengths — Susan Sarandon was understated and naturalistic as Bette, while Jessica Lange (outfitted with much makeup to make her resemble Joan) was playing her role as if Crawford was trapped in one of her own melodramas;

— the production design, in a note cribbed from “Mad Men,”

overwhelmed and wound up distracting from the proceedings;

— the dialogue that conveyed the singular message (that older actresses have trouble finding good parts) was overripe, and the message was conveyed at least three to four times in each episode in very explicit dialogue;

— the emphasis on the lurid events of the characters' lives seemed to imply that producer-scripter Ryan Murphy wanted it both ways — to pay tribute to these two women who were considered outmoded in their middle age, but also to mock their outmodedness constantly;

— and certain real-life individuals were included simply to “add detail,” as with a terribly cloying frame device in which Joan Blondell (Kathy Bates) and Olivia de Havilland (Catherine Zeta-Jones) are interviewed for a documentary about the “feud.”

This aspect, of having things both ways, came to the fore in the final episode, in which the focus was primarily the “downfall” of Joan Crawford. The moment where she puts on a “Trog” mask (as the Doors "The End" plays!) was probably the litmus test of whether you liked or hated the show's approach — some loved its audaciousness as a metaphor for the lousy state that Crawford's career was in; others recognized it as a bid to get a cheap laugh out of that lousy state. Was it surreal, or tragic, or just a cheap shot to evoke a laugh at a washed-up Hollywood icon? Depends on how you view it.

There was no such uncertainty about the character of Robert Aldrich in the miniseries. He was played by the incredibly talented Alfred Molina, who made a three-dimensional being out of the character in the script. The only problem is that scripter-creators Ryan Murphy, Jaffe Cohen, and Michael Zam had decided that it was best for their version of events that Aldrich be depicted as a hack director who had little control over his career and his pictures.

— the dialogue that conveyed the singular message (that older actresses have trouble finding good parts) was overripe, and the message was conveyed at least three to four times in each episode in very explicit dialogue;

— the emphasis on the lurid events of the characters' lives seemed to imply that producer-scripter Ryan Murphy wanted it both ways — to pay tribute to these two women who were considered outmoded in their middle age, but also to mock their outmodedness constantly;

— and certain real-life individuals were included simply to “add detail,” as with a terribly cloying frame device in which Joan Blondell (Kathy Bates) and Olivia de Havilland (Catherine Zeta-Jones) are interviewed for a documentary about the “feud.”

This aspect, of having things both ways, came to the fore in the final episode, in which the focus was primarily the “downfall” of Joan Crawford. The moment where she puts on a “Trog” mask (as the Doors "The End" plays!) was probably the litmus test of whether you liked or hated the show's approach — some loved its audaciousness as a metaphor for the lousy state that Crawford's career was in; others recognized it as a bid to get a cheap laugh out of that lousy state. Was it surreal, or tragic, or just a cheap shot to evoke a laugh at a washed-up Hollywood icon? Depends on how you view it.

There was no such uncertainty about the character of Robert Aldrich in the miniseries. He was played by the incredibly talented Alfred Molina, who made a three-dimensional being out of the character in the script. The only problem is that scripter-creators Ryan Murphy, Jaffe Cohen, and Michael Zam had decided that it was best for their version of events that Aldrich be depicted as a hack director who had little control over his career and his pictures.

He is steamrollered by his two stars, can't cope with the inherent greed and nastiness of Jack Warner (despite one big defiant scene where Aldrich tells off Warner when Baby Jane is a hit), and he is a portly playboy who is impotent in bed with his wife (nice personal attack, that — Murphy and co. really decided to decimate Aldrich the man once they had completely torn apart Aldrich the artist).

Murphy's tremendous success in television is that he's a very good packager — “Glee” is a package, “American Horror Story” is a package, and “Feud” is nothing more than a package (the next feud has been announced as Prince Charles and Lady Diana — if divorce is a feud, there sure are a helluva lot of them….). The characters in such packages need to be simplified — as in reality shows where reality takes a back seat to the fact that certain participants are assigned roles like “the bitch,” “the ladies man,” “the jock,” “the older know-it-all,” or “the girl next door.”

For “Feud,” it was “the fat gay character actor” (Victor Buono), “sassy old lady” (Joan Blondell), “ridiculously rigid German servant with a Hispanic nickname" (Crawford's maid, “Mamacita”), and so forth. Even the characters of Davis and Crawford were oversimplified, intended to represent the ways that the two middle-aged stars dealt with their fates.

But the complete decimation of Aldrich was the most fascinating hatchet job in the show, since Aldrich was first and foremost a subversive artist, a filmmaker whose work was filled with crazy energy, sudden violence, emotional turmoil, endless imagination, and best of all, total sincerity. To say that “Feud” was intended as a camp exercise is obvious — the makers avoided the excesses of Mommie Dearest, but even Frank Perry resisted the urge to have Faye Dunaway put on a “Trog” mask.

The depiction of Aldrich in the series — which, like most American TV product, was too long — brought me back to his work and its crazy ingenuity. Murphy and his colleagues haven't got a scintilla of Aldrich's talent, and none of his subversive tendencies, so seeing them “cut down” a wonderfully adventurous (and yes, sometimes blissfully eccentric and perverse) artist wasn't just demoralizing for his cultists but also wildly inaccurate.

The series touched on Aldrich's career from 1962-64. At the

point leading up to Baby Jane he was in need of a hit — his

preceding four films had all flopped at the box office (despite being, like all

his work, stylishly shot), after he had had a very good run of eight diverse

and brilliantly stylish movies in the Fifties. It's important to know, however,

that he wasn't just a director-for-hire looking for a solid meal ticket. He was

born into a wealthy family (his cousin was Nelson Rockefeller) and was subsequently disowned when he opted for a career in the movie industry. He worked his

way up slowly in the business, serving for a long time as a production

manager and second assistant director before he became first assistant director

to artists like Renoir, Milestone, Polonsky, Wellman, Losey, and Chaplin.

He directed TV dramas before and after his first two pictures (both B-budgeted) were made; a friendship sparked with Burt Lancaster led to his first two bigger budgeted films, the radical Apache (1954), in which a Native American warrior is a charismatic hero, and Vera Cruz (1954). All of the films from this early period are highly watchable but the last-mentioned is the best of the bunch, a vibrant, large-scale Western with Gary Cooper and Lancaster as two soldiers of fortune who join up with the governmental forces during the Mexican revolution, and then switch sides to aid the rebels.

He directed TV dramas before and after his first two pictures (both B-budgeted) were made; a friendship sparked with Burt Lancaster led to his first two bigger budgeted films, the radical Apache (1954), in which a Native American warrior is a charismatic hero, and Vera Cruz (1954). All of the films from this early period are highly watchable but the last-mentioned is the best of the bunch, a vibrant, large-scale Western with Gary Cooper and Lancaster as two soldiers of fortune who join up with the governmental forces during the Mexican revolution, and then switch sides to aid the rebels.

In the seminal book on Aldrich by Alain Silver and James

Ursini, What Ever Happened to Robert Aldrich? (Limelight

Editions, 1995), the filmmaker is quoted as saying, “I must create and I can't

always create what I want artistically and culturally under present methods.

[So] I relax by working… since I have no hobbies such as girls, horses, cards,

etc etc, my principal preoccupation other than pictures is politics.” That

interest fed into his best work, as he was resolutely left-wing and was lucky

enough to not be ensnared by the blacklist. As a result his films are the best

Lefty features to be made in Hollywood during the Fifties, alongside the work

of Nicholas Ray.

This tendency is felt in his films, with the struggle between the rebels and the government in Vera Cruz providing a good example of the humanization of those opposing inhumane leaders (symbolized by the ever-unctuous George Macready and the always smiling Cesar Romero, described here as “Crocodile Teeth”). Aldrich continued to make inherently political films until his last superb picture, Twilight's Last Gleaming, in which a crazed general takes over a nuclear facility to force the government to reveal the actual truth of the Vietnam War, namely that it was a farce and the government knew this all along.

This tendency is felt in his films, with the struggle between the rebels and the government in Vera Cruz providing a good example of the humanization of those opposing inhumane leaders (symbolized by the ever-unctuous George Macready and the always smiling Cesar Romero, described here as “Crocodile Teeth”). Aldrich continued to make inherently political films until his last superb picture, Twilight's Last Gleaming, in which a crazed general takes over a nuclear facility to force the government to reveal the actual truth of the Vietnam War, namely that it was a farce and the government knew this all along.

Aldrich was thus a filmmaker with a conscience as well as being a superbly talented crafter of images. He was often confused in his later years with Robert Altman, and the one thing he did have in common with the younger Altman was that both had an incredibly fertile period — for Altman it was the early Seventies, for Aldrich the mid-Fifties — in which they made several films in different genres, each of which revamped and reworked the genre.

Altman supplied new models for the genres in question, while Aldrich had been content to turn the genres “upside down” (that was the actual expression he used about some of his projects, per the Silver/Ursini book). His fifth feature, Kiss Me Deadly (1955), was hailed as a “nuclear noir” by French critics and is placed by most writers as the end of the noir cycle (with a very small handful of classic noirs coming after it). This sounds like sheer hyperbole, but I'll say it: If it were the only thing Aldrich ever made, it would be enough to guarantee him a place in the Pantheon.

It's an incredible act of subversion. Aldrich took a bestselling novel by pulpsmith Mickey Spillane and did indeed turn it upside down. He made the hero, Mike Hammer, into an openly sadistic sleazeball (who takes divorce cases — the sign of a true loser in the p.i. business) who wanders through an incredibly eye-catching L.A. filled with “high art” all around him (paintings, classical music, 19th century sonnets, opera arias), and he ignores all of it. He's not even that interested in the sports cars and dames that throw themselves at him — he's only interested in revenge and things that pique his curiosity.

The film builds to an astounding end, which has been softened by the reintroduction of some missing footage — as a result, the now commonly-seen version of the picture (on TCM and on the Criterion disc) includes the softer, more “digestible” ending, instead of the “end of the world” vision that concluded the film for so long. In the process, Aldrich uses oblique angles, masterful editing, and crazy set design (the apartments are either flophouse-gritty or bachelor-pad beautiful) to convey Mike Hammer's world, a place where Aldrich noted “the ends justifies the means.”

In an interview included in the Silver/Ursini book, Aldrich notes that the French Cahiers posse attributed too much profundity to Kiss Me Deadly (1955), that he wasn't intending for it to make a social statement. It definitely does, though, since it combines the beautiful surfaces and innate narrow-mindedness that, decades later, became the raison d'etre of “Mad Men.” When Aldrich was doing it, though, it was in the wake of Joseph McCarthy and similarities between the take-no-prisoners Mike Hammer and the noted Commie-hunting Senator were, I'm sure, entirely intentional.

Aldrich's next film, The Big Knife

(1955), is his first expose of show business. The Aldrich seen on “Feud” is a

blunderer, a guy who keeps dueling with studio heads and needy stars but who

has no real control over his pictures. The real Aldrich made three films that

are about the ways in which show biz can destroy performers —

Knife, Baby Jane, and The Legend

of Lylah Clare. Add to that trio The Killing of Sister

George and even … All the Marbles, and you have

additional portraits of women being mocked and diminished in the business. The

only male to be ruined by show-biz in Aldrich's films is Jack Palance's lead

character in Knife.

The film does wind up being corny, but that is because Clifford Odets' work doesn't age well. The play the film is based on was “of the moment” at the time it appeared and had the vague air of transgression, but the dialogue is horribly stilted and action is predictable at best. Despite these impediments, the film still was an open act of hostility by Aldrich against the film studios, as he made a movie that openly talks about the ways in which the studios would quell crimes their stars had committed and even “silence” those who spoke out about those crimes.

The over-the-top characterizations do date, but the film is still incredibly watchable because the cast is sublime and they're more than eager to deliver the ham. Take for instance this argument scene that pits anguished movie star Jack Palance and his totally powerless agent (Everett Sloane) against the completely corrupt studio head (Rod Steiger, in full throttle, playing a role intended to mock Harry Cohn) and a studio “fixer” (the always creepy Wendell Corey).

The film does wind up being corny, but that is because Clifford Odets' work doesn't age well. The play the film is based on was “of the moment” at the time it appeared and had the vague air of transgression, but the dialogue is horribly stilted and action is predictable at best. Despite these impediments, the film still was an open act of hostility by Aldrich against the film studios, as he made a movie that openly talks about the ways in which the studios would quell crimes their stars had committed and even “silence” those who spoke out about those crimes.

The over-the-top characterizations do date, but the film is still incredibly watchable because the cast is sublime and they're more than eager to deliver the ham. Take for instance this argument scene that pits anguished movie star Jack Palance and his totally powerless agent (Everett Sloane) against the completely corrupt studio head (Rod Steiger, in full throttle, playing a role intended to mock Harry Cohn) and a studio “fixer” (the always creepy Wendell Corey).

Aldrich's next film was a “woman's picture” that was crafted into a vehicle for Joan Crawford, Autumn Leaves (1956). As with this other Fifties genre films, he obeys the rules of the genre here while also overturning them with the inclusion of a “psycho” twist in the plot. Thus, in a Crawford weepie we wind up seeing the breakdown of her “dream man” (Cliff Robertson), to the point where he is put in a mental hospital and given shock treatment. Psychiatry was definitely a preoccupation in Fifties pop culture, but here it comes out of left field — we spend the majority of the film wondering how poor Joan will be shafted, never suspecting that the dream man is also a victim (of his scheming ex-wife, Vera Miles, and his lecherous dad, Lorne Greene!).

This film established a rapport between Crawford and Aldrich that of course factored into Baby Jane (although the “Feud” scripters decided that Aldrich favored Bette, and thus shafted Joan by the time Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte came around). Aldrich's reputation rests for many viewers on his skill at directing “men's movies” like his giant hit The Dirty Dozen (1967), but he did contribute some great visions of women in his films. The characters were all beleaguered and/or ruined by the end of the pictures, but that in itself is a commentary on women's place in society during the period that he made the films. (And, besides, many of his noblest male characters were ground under as well.)

Here is a great scene from Autumn Leaves:

The last superb Aldrich film in the Fifties (followed by the

lean quartet that put him in financial jeopardy — the one true note in “Feud”)

was Attack! (1956). It's an incredibly subversive (that word

again) picture because it confronts the same issue that informed John Ford's

Fort Apache (1948) — an indecisive leader (Henry Fonda in

Ford's film, Eddie Albert here) being called on his behavior by a strong soldier

(John Wayne in the Ford, Jack Palance here).

Like The Big Knife, the film is based on a play (by Norman Brooks), but this time out, the result is not as stilted, thanks to a script by James Poe. While John Ford and scripter Frank Nugent's take on the scenario was that one doesn't report the wimpy leader who winds up killing one's men (Wayne's character upholds Fonda's legacy), the Aldrich variant is to emphasize the lethal aspect of such a leader, and the importance of the common man standing up to such dangerously misguided authority — although it is William Smithers' character who winds up having to do it, since Palance dies dramatically in the film (another great Aldrich touch — many of his heroes die!).

While Fuller's Fifties war pictures are terrific and Ray's entry in the genre (Bitter Victory) is incredibly good, Attack! goes straight to the heart of the matter and questions the leadership that makes soldiers walk into perilous situations and then covers up the sheer pointlessness of their death. Aldrich continued this debate in Twilight's Last Gleaming.

Like The Big Knife, the film is based on a play (by Norman Brooks), but this time out, the result is not as stilted, thanks to a script by James Poe. While John Ford and scripter Frank Nugent's take on the scenario was that one doesn't report the wimpy leader who winds up killing one's men (Wayne's character upholds Fonda's legacy), the Aldrich variant is to emphasize the lethal aspect of such a leader, and the importance of the common man standing up to such dangerously misguided authority — although it is William Smithers' character who winds up having to do it, since Palance dies dramatically in the film (another great Aldrich touch — many of his heroes die!).

While Fuller's Fifties war pictures are terrific and Ray's entry in the genre (Bitter Victory) is incredibly good, Attack! goes straight to the heart of the matter and questions the leadership that makes soldiers walk into perilous situations and then covers up the sheer pointlessness of their death. Aldrich continued this debate in Twilight's Last Gleaming.

By the time Aldrich reached What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, he was indeed recovering from four flops in a row. Three of the four films were relatively “normal,” but one is a true gem, Ten Seconds to Hell (1959). A post-war drama set in Germany, the film has one silly conceit — that six American actors, led by Jack Palance and Jeff Chandler, play the lead characters, a sextet of German demolition experts who make a deal to defuse unexploded bombs around Germany for the Allies for a period of three months.

The rest of the film is simply terrific. Aldrich makes certain to put no music under the bomb disposal scenes, so the editing is the only way that the tension is conveyed (no corny “thriller music”). The premise of the film is a truly existential one (thus the utter worship of Aldrich in France, while he was and is still barely celebrated in his home country). It seems that Chandler is such a devil-may-care soul (with a mean streak) that he makes a bet with his colleagues that he can outlive them all — they agree to make a fatalistic wager in which the participant who lives the longest collects money from the salaries of the other five.

It’s obvious that the film will end up being a deadly showdown between Palance and Chandler, but even there Aldrich has some fatalistic surprises in store. Given that some American critics faulted him for being over-the-top in terms of violence, Ten Seconds is a perfect example of the restraint he could exercise when it benefitted the storyline. And the best part of this whole thing? The film was a coproduction of Seven Arts and Hammer Films (yes, that Hammer Films).

“Feud” repeatedly showed Aldrich struggling with interference from Jack Warner on Baby Jane. The only time the true nature of the film — which was a production created and developed by Aldrich — was referred to in the show was when it was necessary to have a “worried Bob Aldrich scene.” Otherwise viewers never learned that, from his third film (Apache, in 1954) on, Aldrich was a trailblazing independent producer who made deals with studios to complete/release his films. His taste in material was always slightly “odd,” thus his interest in the Baby Jane novel and genre-jumping once more to create a distinctly modern horror film that traded on the past as part of its terror.

Aldrich knew he would take the grief for whatever went wrong on his projects. “… the Director is always held accountable for every picture that fails, and should a picture succeed the Director only shares that dubious distinction. However, the bottom line is the Director is in the trenches every day.” [Silver/Urisini, p. 40]

He likened show business to gambling, where you want to “stay at the table” as long as you can. “Staying at the plate or staying at the table, staying at the game, is essential. You can't allow yourself to get passed over or pushed aside. Very, very talented people got pushed aside and remained unused. That's the problem: staying at the table.” [p. 346]

After the three years of his life chronicled in “Feud” (where the producers saw fit to show him suffering while working with Sinatra on Four for Texas, to make him an even more beleaguered wimp), Aldrich went on to make a number of audacious and challenging films. A few missed the mark, some are good entertainment, and a handful are truly great movies. I offer a few of the more ambitious and sharply challenging works below.

*****

What is most fascinating about Aldrich’s career after Baby Jane is that when he had his single biggest hit, The Dirty Dozen, he immediately made two of his most daring films. The first of the two was The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968), his ultimate statement on women being ground up by the Hollywood system. It's similar to some earlier show-biz films (Sunset Blvd, The Goddess), but it creates its own weird mythology and has one of the best “grotesque” endings in movie history. Kim Novak reportedly was disappointed with the picture, primarily because Aldrich dubbed in a German actress's voice for one of her incarnations, but she comes off beautifully in the piece.

His next film was even more controversial. The

Killing of Sister George (1968), also based on a play, has been

hailed as ground-breaking and incredibly important in depicting lesbians on

film, and has also been criticized for being too grotesque in its

characterizations (particularly the Coral Browne character). The film is dated

in various aspects but it was incredibly daring for its time, as the long gay

bar sequence demonstrates. It also featured a trio of excellent leads (although

most attention goes to Susannah York's “femme” character). Here is the gay bar

scene:

Aldrich’s last Western, Ulzana’s Raid (1972),

is a great piece of entertainment, as well as being a pungent statement on the

relationship between white authorities and the Native American (as had Aldrich's Apache). The film was

his reunion with Burt Lancaster, with whom Aldrich made four of his finest

films (three of them Westerns). Here is a scene that gives a feel for the movie’s

tone (and was unfortunately trimmed for the U.S. version):

Aldrich's “guy movies” range from war pictures to one of the

most one-on-one violent films of its era, Emperor of the North

Pole (1973). The film ranks with Walter Hill's Hard

Times (1975) as one of the great “fighting to survive in the Depression”

movies (with the emphasis on the actual fighting).

The fact that Aldrich set Lee Marvin against Ernest Borgnine for this match of the century made the film even more of a favorite of those who love grizzled character actors (not forgetting Keith Carradine, who is excellent as the young hobo “student” of Marvin). This lighter-than-air trailer tries to sugarcoat the nastiness of the pic:

The fact that Aldrich set Lee Marvin against Ernest Borgnine for this match of the century made the film even more of a favorite of those who love grizzled character actors (not forgetting Keith Carradine, who is excellent as the young hobo “student” of Marvin). This lighter-than-air trailer tries to sugarcoat the nastiness of the pic:

Aldrich's last crime film is an incredibly good neo-noir, Hustle (1975). One of Burt Reynolds' handful of non-forgettable Seventies pics (along with Aldrich's The Longest Yard), the film finds him playing a private eye in love with a hooker (Catherine Deneuve) who battles a homicidal attorney (played by the wonderfully villainous Eddie Albert). Here is a scene between Reynolds and Deneuve:

The last great Aldrich film — although I do have a great

fondness for his women's wrestling adventure, ...All the

Marbles (1981) — is Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977).

As noted above, it's a riveting film that starts out as a kind of update on the

Fail-Safe/Seven Days in May nuclear-paranoia

thriller, but soon becomes a pointed drama about governmental duplicity as it

goes along.

I don't know when, if ever, another great Hollywood director

will ever be depicted on an ongoing TV drama. Hopefully the depiction will be

nearer to the facts and a bit more respectful. I ain't holdin' my breath….

Thanks to Charles Lieurance for the screen-grab.

Thanks to Charles Lieurance for the screen-grab.