Now onto the feature films and other media depictions of the Insidious One. Comic books will be left out (although you can read the Wally Wood-drawn “Mask of Fu Manchu” comic here), as well as live productions, and obscure variations and pastiches on the characters. The key to these films, simply put, is the amount of “Fu content” they contain.

As with Golden Age Hollywood movies featuring great comedians and — the most obvious — gangster and monster movies, these items rise and fall based on how much time that Fu is center stage. The longer he is offscreen, the more insufferable the film or show is.

The first films made from the Fu Manchu novels were two series of silent cliffhangers made in England. These films (as with the later U.S. radio series) were note-for-note adaptations of the books, which initially were compilations of stories Rohmer wrote for magazines. It should be noted that the Fu Manchu films basically reprise incidents and situations found in the first six or so novels; the U.S. radio series was one of the few instances where three more of the novels were adapted. While the Republic serial was named for one of the later novels, it reached back to situations found in earlier books.

The second serial, The Further Mysteries of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1924), is not readily found on the Internet, but The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1923) is present in its entirety. Directed by A.E. Coleby, the serial moves much slower than the gold standard of silent serials, which are surely those directed by Louis Feuillade and German items like The Spiders by Fritz Lang.

Mystery established the pattern that one will encounter in all the subsequent Fu films, where one desperately wants to fast-forward through the scenes that don’t feature Fu or his colleagues in crime. Nayland Smith, Petrie, and the other good guys do chase after Fu, but they also spend an inordinate amount of time talking in rooms. These scenes are lethal, whether they’re in a 1920s serial or a 1960s adventure pic.

|

Coleby also gave up on trying to make his Arabic and Eurasian female characters look Asian — they are simply white actresses dressed in flamboyant outfits with frizzy hair. (Did one assume a frizzy-haired woman looked “foreign” in 1920s England?)

The one redeeming aspect in Mystery is the recreation of the tortures described in the books, from whipping to “the Six Gates of Joyful Wisdom” (in which the victim is put in a wire cage with partitions, through which rats come and gnaw on different body parts). The most memorable scene for this viewer was a dream sequence in which Petrie dreams of being Fu’s slave. He and three other scientists mix strange potions in chains under the watchful eyes of Fu, while another slave-scientist is being flogged by a henchman.

Like the later TV series, Mystery has no cliffhangers — it is composed of 15 short, self-contained films that have conclusive finales. This robs the serial of a lot of its power and makes it best seen in doses of 2–3 episodes at a time and no more. (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

Fu was next played by Warner Oland, the Swede who excelled in “yellow face” roles (including his signature character, Charlie Chan), in a trio of pre-code features. The first two of the films, The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929) and The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930), are flat-out dull, as the scripters crafted a prim and proper script, consisting of too much talking in rooms (making the pictures seems like poorly crafted stage plays); one of the incessant talkers is the later TV “Commissioner Gordon,” Neil Hamilton. The torture aspect of Fu’s activities is downplayed, since it wouldn't involve talking.

And far, far worse was the fact that the scripters decided Fu needed a reason to be a world-conqueror. In this and the subsequent two films starring Oland, Fu carries out his dastardly plots because his wife and son had been killed in the Boxer Rebellion!

The only truly watchable entry in the Paramount pre-code trilogy is Daughter of the Dragon (1931). The film is quite unique, in that Fu Manchu dies onscreen (only to return for select moments as a specter) and then the leading criminal is his daughter, Ling Moy, played by Anna May Wong. She is a hesitant crime lord, who is very much in love with one of the tedious British characters. The script is as leaden as in the two preceding films, but the notion of a woman supervillain is enough to relieve some of the tedium. (And it was made three years before the Dragon Lady debuted in “Terry and the Pirates.”)

Wong later regretting taking the role, saying in 1933, “Why is it that the screen Chinese is always the villain? And so crude a villain — murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass! We are not like that. How could we be, with a civilization that is so many times older than the West?”

The most interesting scenes find Ling Moy talking to a Chinese police detective, played by Sessue Hayakawa. Wong adopts a more formal way of speaking here, so her American accent sounds vaguely like the British accents heard in the other scenes. This clashes with Hayakawa’s thick Japanese accent, giving a particularly weird tone to the usual leaden dialogue found in these films.

While this piece was being assembled (read: yrs truly was in the midst of a Fu binge) it was announced that a box set of the five Fu films starring Christopher Lee was being released around Halloween. Those films are reviewed below — but suffice it to say that one would have to be a massive fan of Christopher Lee to see four of those films more than once. Not so with the next two entries, which are without question the best of all the FM features.

The first of those two is inarguably the best and most outlandish of the Fu movies, The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), starring a post-Frankenstein (1931) Boris Karloff. Mask was made by the very classy MGM with an A-budget and eye-catching images by director Charles Brabin and cinematographer Tony Gaudio (The Adventures of Robin Hood).

The film captures the thrilling, pulpy, and deviant aspects of Rohmer’s work. And yes, it puts forth both the inherent racism in the Yellow Peril scenario and the fact that any viewer worth his/her salt will enjoy Fu’s violence and destruction and find the British colonialist intolerably smug and worthy of their eventual destruction. Cue the line restored to the film in recent decades: “Kill the white man and take his woman!”

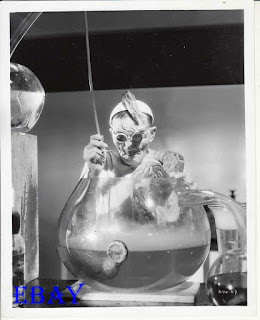

Karloff’s reputation has meant that the film was categorized as horror — and it shares with the great Universal monster movies of the early ’30s a mad scientist motif, as here Fu has the same kind of sizzling, spark-flinging machinery as Dr. Frankenstein. (And created by the same man, Kenneth Strickfadden.)

|

| A cut scene of a "snake man." |

The basic parameters of the storyline qualify it as pulp action-adventure, but there is also the standard parlor-mystery level and a pre-noir look at an underworld. And as for Asian “exotica,” the director who set the standard was von Sternberg, and Mask is the closest approximation to a thriller directed by him.

Karloff was, hands down, the best actor to play Fu, and thus his performance here is exceptional. His FM isn't any old supervillain, he is the most malevolent and fearsome villain to ever be set loose on colonialist dullards. He emphasizes the sadistic nature of the character and exhibits glee when torturing the Brits. It’s hard to pick a favorite of these scenes, but one in which British Sir Lionel Barton (Lawrence Grant) is placed beneath a bell in order to be rendered both deaf and insane is a sure favorite.

The 1994 book Hollywood Cauldron by Gregory William Mank contains a chapter about Mask with intriguing quotes from Karloff, none of which are sourced. Mank apparently did a very sizeable amount of research for this tome, but several of the quotes in the book are unsourced; as he thinks Freaks and Mask are both rather wretched, laughable films, he’s therefore to be put in the “Caveat lector” category. Nevertheless, his unsourced quotes from Boris include the fact that there was no finished script when shooting began on the film.

Karloff also complained about the “bad makeup” and the fact that he would be given full script pages the day of shooting that contained long speeches written in “impeccable English,” then told that other speeches in pidgin English had been substituted: “They had five writers on it, and this was happening all through the film. Some scenes were written in beautiful Oxford English, others were written in — God knows what!”

The other standout performance is Myrna Loy as Fu’s daughter Fah Lo See. As in every depiction of the characters, she suffers lovesickness over one of the British heroes, but the most surprising scene — which makes the film a true pre-code work (and leagues livelier than the Warner Oland trilogy) — is the moment where she exhibits a kinky intensity as hero Terrence Granville (Charles Starrett) is being whipped in front of her.

Enter the Hollywood Cauldron book again. Here, Loy is quoted from her memoir Myrna Loy: Being and Becoming (1987) as saying that she disliked the script and told producer Hunt Stromberg that the character was “a sadistic sex maniac.” She declared that her complaints resulted in the “character’s worst excesses being toned down.” She also stated that “Boris and I brought some feeling and humor to those comic book characters. Boris was a fine actor, a professional who never condescended to his often unworthy material.”

Mask was the only time the proper balance was struck between the utterly crazy and staid aspects of Rohmer’s writing in a movie. This is reflected in the torture scenes, which are paced wonderfully and shot like incidents in a cliffhanging serial.

One wishes there had been other Karloff Fu films (he made five Mr. Wong films, after all!), but the U.S. State Department stepped in and asked MGM not to revive the character, as American-Chinese relations would be damaged. (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

The next incarnation of the Insidious One was the U.S. radio show The Shadows of Fu Manchu (1939). The show featured recreations of scenes from the first nine novels and was quite an odd item, since each episode is only 15 minutes long, and the opening and closing were to be announced live on whatever station aired the show. So, the copies that we have are “clean” versions that have long intro and outro bumpers of music.

The best-known performer was later Lucille Ball cohort Gale Gordon as Dr. Petrie. He and the other cast members recited bushels of dialogue that came straight from the novels, with expository dialogue added in. At least — unlike the silent serial and later, horrible TV series — the Shadow radio series (which clearly wanted to be mixed up title-wise with the actual Shadow program) had every episode end with a cliffhanger. [Note: Two earlier Fu radio shows — one American, one British — are lost to the ages.]

The year after the radio show, the serial Drums of Fu Manchu (1940) was released. Drums is right below Mask as one of the most entertaining Fu movies — it’s a great example of the top-notch serials made at Republic, and although scripted in the classic serial mode (in which every single action seems pointed toward that week’s cliffhanger), it’s one of the few consistently exciting recreations of Rohmer’s “race against time” writing.

Henry Brandon was no Karloff, but his portrayal of Fu is diabolical and threatening-yet-clever; thus he is the most interesting character in the serial. Although Rohmer made a point about noting that Fu’s fluent English was “both sibilant and guttural,” Brandon adopts the “sneering villain” voice that was often used on radio shows and was later immortalized by Richard O’Brien in his nasal performance as Riff Raff in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. (Physically, Riff may look like a mad scientist’s assistant, but he speaks like a consummate supervillain.)

Brandon is quoted from a 1986 interview with author Gregory William Mank in Hollywood Cauldron about the film: “… I’d go to a theater nearby here in Hollywood, where they showed it, and sit among the kids (they never recognized me) — and I loved their reactions. Within two or three episodes, they were on my side! It was because I was brighter than the others, and the kids went for intelligence, whether it was bad or good.”

“But the PTAs — they didn’t like it at all, because the kids would wet their beds after seeing it. And the Chinese government raised plenty of hell! And that’s childish, because I consider Fu Manchu a fairy tale character — it’s not to be taken seriously for God’s sake!” [Mank, p. 83]

Those viewers rooting against Nayland Smith will be happy to see him nearly turned into a lobotomized dacoit by Fu. “Dacoit” being the most-used phrase in Fu movies and novels — it refers to Indian and Burmese criminals, but in this usage simply means Fu’s henchmen. And the titular drums are a terrific gimmick — at the end of every chapter, the drumbeats come on the soundtrack, signaling doom for the heroes.

As happened with Mask, sequels to the serial were planned, but the U.S. government requested that no further Fu adventures be filmed, as the Chinese were our ally at this time in the fight against Japan.

The 1956 TV show The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu (1956) was made by Republic’s TV arm (Hollywood Television Service), but it’s the complete opposite of Drums — a dull, thrill-less “action” series. The show is dreary and — insult of insults — it’s the most easily found of the Fu movies, since it fell into the public domain. (An earlier TV pilot starring John Carradine as Fu (!) has survived but is under lock and key.)

Most inexcusable is Glen Gordon’s weirdly lazy turn as Fu. Speaking… slowly… to… approximate… an “honorable Chinese” accent, Gordon’s portrayal is the most racist (if such a thing is possible) of all portrayals of FM. His mustache looks pasted on, his intensity is nil, and the accent is just beyond shameful.

Two episodes rise above the rest — one where Fu allies with a gangster (the great character actor Ted de Corsia) and another that is a clear foreshadowing of They Saved Hitler’s Brain, in which Fu kidnaps a plastic surgeon to get an unnamed “dead” dictator a new identity. And then from an HQ on a remote island, Hitler (yes, it’s him) tries to take over the world, for good this time. But he’s defeated within the 26-minute running time (the closing credits for the whole series find Fu losing a metaphorical chess game with Nayland Smith), and a bizarre and amusing alliance is just tossed away in an episode of an otherwise forgettable TV series.

The star of the five 1960s Fu Manchu films produced by Harry Alan Towers, the great Christopher Lee, once said that only the first of his Fu features was worth making — he was quite right. Because if you thought the Lee/Dracula films got weaker and weaker as time went on, those pictures seem like cinematic landmarks compared to the second through fifth Lee/Fu movies.

The Face of Fu Manchu (1965) provides the best vision of Fu’s manic desire to conquer the world; it is the first time we see many dead bodies on display. In one scene, Fu poisons an entire town and the British lawmen see the results — streets with bodies strewn about. So this time out Fu really does seem like a violent threat, not just a transient madman who kills a few select victims.

Lee is indeed at his best here, since he took all his roles (no matter how thin or awful they could be) very seriously and he plays Fu with true conviction. The other cast member who impresses is Tsai Chin, who plays Fu’s daughter Lin Tang. She occupies a significant position in these films, because she was the first and only Asian woman to play that role and the only Asian besides Anna May Wong to play a starring role in a Fu film. She was also one of only two regulars in the Lee/Fu movies. (The other was Howard Marion-Crawford as Dr. Petrie.)

One of the odder developments, though, was that even as it became commonplace to see more sex and violence in British exploitation, there was still a limit in the Fu films. This is clear where when Lin Tang wants to whip a man (taking direct action, as opposed to Myrna Loy’s character, who just liked to watch) and is prevented by her spoilsport father.

Face is without question a very good Fu feature. All that followed was dross, and embarrassingly bad dross at that. (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966) show the James Bond influence. It’s a “slave chick” movie (paging Doctor Tongue and Hugo, from “SCTV”) and has some enjoyably lurid moments, but even with a large group of Fu’s female slaves on prominent display, it’s still a pale imitation of Face. Although the wonderful Burt Kwouk does show up as a henchman. (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967) should work for a few reasons, including the fact that it was partially shot in Hong Kong and has a fairly decent (if familiar) plot twist, in which a Fu henchman is given plastic surgery to look like Nayland Smith (which none of his friends notices, naturally enough, although his skin is gray and his eyes are dead).

By this, the third Lee/Fu outing, there was no disguising that nearly everyone involved was going through the motions. This would reach epic proportions in the last two Lee/Fu disasters. (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

Shot in Spain and Brazil, The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968) is a cut-and-paste creation by that most beloved yet least talented of cult favorite filmmakers, Jess Franco. Franco accomplished in film after film the trick of making utterly unsexy exploitation. (How do you fuck up a women’s prison picture? Watch Jess’s entries for the answer.) Here he made a film about Brazilian bandits that he seemingly was going to make anyway and just stuck Fu Manchu into it when he got the gig.

The plot revolves around the aforementioned bandits and a “kiss of death” that Fu’s slave women are ordered to give select victims. The film contains variations on scenes from Face and Brides, and, again, is a remarkably unsexy and un-thrilling specimen.

By this point, Lee was clearly doing his scenes in a very short span of time. (Perhaps a few days, if not a few hours.) Franco’s pacing will seem mercilessly slow to any viewer not in Franco’s cult (where an occasional psychedelic color scheme is greeted as a “style” of filmmaking). (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969) was the last serious Fu movie, and it is perhaps the worst ever, plain and simple. This time out Franco created a film about Turkish intrigue that barely has Fu Manchu in it at all. And when Lee (whose shooting schedule seems to have been a scant few hours, if not a few minutes) is onscreen, he looks as bored as the viewer.

Moving at a glacial pace, Castle is a classic cut-and-paste Franco effort. (And, natch, “effort” is the perfect noun to go with Franco’s name.) Much fun has been poked at the fact that Franco needed footage of a ship sinking, so he simply used scenes from A Night to Remember (1958), but that is somewhat amusing. There are other scenes in Castle that are sheer torture – not in the violent FM sense, but as an example of a filmmaker who had no real idea of what would come next, nor did he care.

This is the film that did what Asian-Americans had wanted to do for decades — it killed off Fu Manchu. (A later 1986 film by Jess Franco called Esclavas del Crimen is an unauthorized adventure of the daughter of Fu Manchu, but when dealing with Jess Franco, enough is more than enough.) (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

A tangential oddity that (sorta) takes place in the ’70s but was made in 1990: Spanish horror star Paul Naschy starred as Fu in “La hija de Fu Manchú ’72,” a short film coproduced by Spanish television. The short was seemingly intended as both a spoof and a tribute to the Fu Manchu mythos, with Naschy appearing as Fu himself, wearing a patently phony mustache.

Nayland Smith and Fu’s daughter are center stage here as well, and a woman who is abducted by Fu’s daughter and whipped onscreen by a henchman. The visuals are tongue-in-cheek and evoke comic book panels and what appear to be much-beloved memories of Mask and the Lee/Fu movies (as well as Bruce Lee movies). The title sequence is a no-budget send-up of James Bond title sequences.

The very last Fu Manchu feature, The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980), was also Peter Sellers’ last film, and it seemed like an atrocity when it was released after Sellers’ death (and his superbly quiet turn in Being There). Viewed through a 2020 lens, it’s just a misconceived and badly paced comedy.

Looking very feeble and unhealthy, Sellers plays both Fu and Nayland Smith. He is surrounded by a very talented cast, including Sid Caesar (who gets nothing to do), Helen Mirren (in her sexpot guise), and the aforementioned Burt Kwouk (who does a cameo with Sellers asking if he’s seen him somewhere before).

There are quite a few Seventies and Eighties comedies that had the terrible pacing of Fiendish Plot (that type of misconceived, patently bad vehicle picture became the specialty of SNL alums). But one can see where Sellers tried his hand at adding to the proceedings, with odd surreal gags that his Goon partner and friend, the genius madman Spike Milligan, could have scripted to a fine turn (including a very Goon-like flying house).

As it stands, the picture was an odd and sad end to Sellers’ career and an equally odd finale to the Fu saga on film. (Further novels were written after Rohmer’s death in 1959, but never sold as well as his initial books in the series had.) (Click the “Watch on Odnoklassniki” link in the thumbnail.)

A suggestion in closing, for those who are new to the character: watch Mask of Fu Manchu first and if you enjoy it, see Drums or Face. After that, you’re on your own, and probably best off reading the books.

And since I’d rather be washed ashore on a desert island with only Jess Franco movies to watch than close out this piece with Nicolas Cage playing Fu in a fake trailer that was part of the “Grindhouse” project, I will leave you with an odder and most definitely funnier vision of Fu, which spawned Sellers’ revelation in Fiendish Plot that Fu’s first name was Fred: the opening of the Goon Show episode that introduced the character “Fred Fu Manchu,” the best bamboo saxophonist in the world.

This is an unusual version of the episode that was part of the Telegoons TV show (1963-64), where old episodes were performed with puppets on television. The three principals returned to redo the episodes without a studio audience.

Sources:

— The Page of Fu Manchu. Editors: Dr. Lawrence Knapp and Dr. R. E. Briney. 1997–2009.

— Master of Villainy: A Biography of Sax Rohmer, Cay Van Ash and Elizabeth Sax Rohmer, 1972, Bowling Green University Popular Press.

— Hollywood Cauldron, Gregory William Mank, McFarland and Company, 1994.

— “The Word of Fu Manchu,” William Patrick Maynard, Blood ’n’ Thunder, Nos. 36-37, winter-spring 2013, pp. 102–113.

— “Fu Manchu and China: Was the 'yellow peril incarnate' really appallingly racist?” Phil Baker, The Independent, Oct. 20, 2015.

— “Fantastic Elements in the Works of Sax Rohmer.” Colombo & Company website, Nov. 2010–Sep. 2012