To close off my discussion of Allan

Sherman, I need to review the book that set the Sherman “renaissance”

in motion, Mark Cohen’s biography Overweight

Sensation: the Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman. In my last entries on Sherman, I disagreed with

Cohen’s verdict on Allan’s two books — his biography, however,

is a fine one that addresses Sherman’s life and work from a number

of different angles.

Cohen’s research is impeccable. In

the first portion of the book, he successfully untangles Sherman’s

quite tangled familial relationships, to the extent of charting where

Allan’s family “disappeared” to when his criminal stepfather

had to quickly flee Los Angeles for getting caught passing bad

checks. He does a similarly excellent job conveying the relationships

that fostered and cultivated Allan’s talent (most prominently, his

unashamedly Jewish maternal grandparents) and those he struggled with

even after the person was long dead (his mother, who did her best to

assimilate, and sublimate her Jewishness).

The book clearly breaks down into three

sections: Allan’s childhood and pre-fame adulthood; his sudden,

massive stardom; and his sad “fall from grace” in show business.

The most interesting aspect of the book is the way that Cohen

analyzes Sherman’s lyrics with the sober-minded intensity of an

academic, while he also displays a fanboy-like affection for this

work, providing us diehard fans with a trove of previously unheard

lyrics that qualify as some of Sherman’s funniest, silliest, and

(not surprisingly) most Jewish songs. Cohen's unearthing of these

lost gems resulted in the first “new” Sherman CD in years, There

Is Nothing Like a Lox.

The childhood portion of the book finds

Cohen taking on the role of storyteller, occasionally making jokes

about the subject matter. When Allan becomes a sudden superstar,

Cohen includes essays about Sherman’s most famous songs, discussing

them in some depth as cultural artifacts and landmarks of American

Jewish culture.

At these points he vaunts Sherman as

perhaps the seminal Jewish humorist of the mid-20th century, studying

his lyrics and designating them as important works of social satire.

This could be seen as taking it a bit too far, were it not for the fact

that Sherman’s lyrics (which Cohen delightfully quotes at length)

were, and are, damned funny and clever.

Like any good fan, Cohen’s emotional

proximity to his subject is communicated throughout the book. He

seems positively outraged when he recounts the many times that

Sherman showed his childish side in public. Allan declared to

journalist Nora Ephron that “My parents divorced when I was 6 and I

spent the rest of my life at Fred Astaire and Dick Powell movies.

This caused me to lose my grip on reality.”

At times, Cohen sounds like a

disappointed parent lamenting the puerile behavior of his beloved

child. The thing that becomes clear, though, from a close reading of

both Sherman’s autobio A Gift of Laughter and Overweight Sensation (and a close listening to his songs) is that his childish behavior was

directly linked to his childlike sense of wonder at the insanity of

the world. His corny pronouncements about the blissful nature of

children’s innocence were the flip side of his ability to write

through the eyes of a youngster (the fact that his biggest hit was

“Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah” was not a surprise). Here Allen

comments on the song (in a video posted by Cohen):

Allan’s childishly simple view of the

world also seems to have allowed him to have the balls... er, chutzpah to write dozens of song

parodies, perform them at parties, and then carve out a musical

career, when he possessed neither a Greek physique nor a great

singing voice. He was clearly a man driven by his instincts — his

best albums were written in a matter of weeks before they were

recorded.

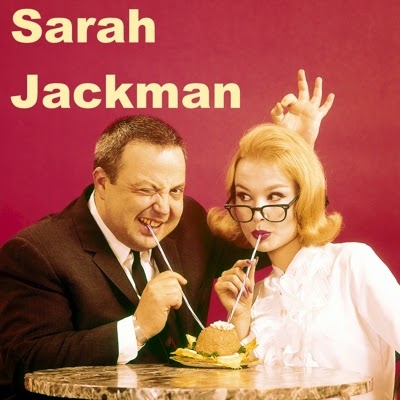

|

| Allen with the cast of I've Got a Secret. |

Sherman, in fact, suffered from the

classic performer’s dilemma: a mixture of self-loathing and rampant

egomania. Cohen chronicles how he indulged in his addictions —

gambling, smoking, and most especially eating — while he was a

young man and then a producer of game shows in both NYC and LA (the

most important one being I’ve Got a Secret,

which he co-created).

Once he hit it big with his first LP,

My Son the Folk Singer, he plunged even deeper

into these addictions and was finally able to indulge in a fourth

that had always been his main obsession growing up (as recounted in

his autobiography A Gift of Laughter and his

chronicle of the sexual revolution, The Rape of the A*P*E*),

namely sex. Cohen was told by the classical pianist Leonid Hambro, a

good friend of Sherman’s, about the orgies he and Allan attended

(whose habituees also included George Plimpton — those lucky

ladies!).

Like many comedians, Sherman was

clearly a major depressive. Despite his chutzpah, he also suffered

from severe self-loathing and a realistic viewpoint about the

vagaries of fame. He never felt comfortable with his success, noting

in Daily Variety “If you can get this lucky all

of a sudden, you can get that unlucky, too.” He added to a reporter

at the New York Journal-American in regard to his

premonitions that his fame would go away, “I'm pledged not to get

desperate.”

Much of the final portion of

Overweight Sensation is given over to the ways in

which Sherman undermined his own efforts in show business with self-destructive and exceptionally naïve behavior. Ultimately, though,

he left us a legacy of brilliant, infernally catchy comedy songs,

which Cohen celebrates throughout the book.

In the final chapter, Cohen goes

past Allan’s death to discuss how Sherman’s music went out of and

back into popular favor. Although at points Cohen seems to be giving

Sherman credit for all modern Jewish-American comedy, it is very true

that Allan’s albums remain masterworks of both wordplay and ethnic

“belonging.” Allan once said to an interviewer, “everyone is

part Jewish.” He wasn’t wrong.

*****

Cohen devotes several pages in the book

to an ongoing set of songs that Allan called “Goldeneh Moments from

Broadway.” Most of the tunes are available on the There Is

Nothing Like a Lox CD, but Cohen also has uploaded several

to YouTube. Sherman introduced the concept at the parties he

performed at in this way: “It occurred to me, what if all of the

great hit songs from all of the great Broadway shows had actually

been written by Jewish people? Which they were.”

On occasional, though, of course, there

was a song that was easily parodied that was written by a gentile. In

this case, Meredith Wilson's “Seventy-six Trombones” from the

smash musical The Music Man was transformed by

Allan into “Seventy-six Sol Cohens” (all of the following postings are from Cohen's YT account):

“Over the Rainbow” becomes

“Overweight People”:

A parody of “Summertime” from

Sherman's Porgy and Bess rewrite “Solly and

Shirl”:

Another song by a gentile, “You're

the Top” by Cole Porter, gets the Sherman treatment:

“There Is Nothing Like a Lox” came from Sherman's Rodgers and Hammerstein variation,

“South Passaic”:

His stirring and very silly “You'll

Never Walk Alone” spoof “When You Walk Through the Bronx”:

Finally, one of the best songs from

Sherman's first LP, one that Cohen talks about for a few pages, Allan's tongue-twisting rewrite of the already pretty

tongue-twisted Irish tune “Dear Old Donegal,” “Shake Hands With

Your Uncle Max”:

Note: Some of the pictures in

this blog entry come from Mark Cohen's website about

Overweight Sensation, which can be found at

allanshermanbiography.com.