|

| Rafelson at the Postman premiere with his stars. |

In the first part of this piece I mentioned the two projects that fell apart on Rafelson in the late 1970s, an adaptation of the novel At Play in the Fields of the Lord and the Redford prison film Brubaker, both of which Rafelson had done much preproduction research for. The story that he had a violent physical encounter with a studio head on the set of Brubaker made the rounds, and he was no longer a “player” in Hollywood. But then his old friend Jack had a project he thought Rafelson could carry off to perfection….

The idea was to remake The Postman Always Rings Twice, returning to the James M. Cain novel and ignoring the reworkings of the book that had taken place in past adaptations of it — which included a classic (but tame) Hollywood adaptation with Garfield and Turner and three foreign versions of the book. (Two are uncredited. The most noted of the trio is Visconti’s 1943 film Ossessione.) Rafelson was indeed a great choice to adapt the book, and the success of his adaptation led to him working in the “fall-back” genre (hardboiled, noir source matter) that he was to return to four more times in his career. To put it plainly, hardboiled stories were ALL he made in the second and last part of his career (1981-2002), except for the very personal adventure film Mountains of the Moon.

Nicholson could write his own ticket by the late Seventies, and so he got Lorimar, the production company, to agree that Rafelson would have no interference from studio heads and would have final cut. What was created was a fascinating film that veers sharply away from the previous American Postman, as Rafelson wasn’t a fan of film noir (a curious fact, cited on p. 19 in Jay Boyer’s book Bob Rafelson: Hollywood Maverick, Twayne Publishers, 1996).

Instead Rafelson wanted his film to be true to its source matter, a tale of explosive sexuality and shifting morality (and loyalties) that had no trace of the romantic about it — until the end where it fell to the two stars to convey the fact that the instinct-driven lead characters might indeed be capable of actual love for each other. The filmmaker chose two excellent partners to craft the film — his first as a director “for hire” but which he did make into a somewhat personal work.

The first of his two key collaborators was cinematographer Sven Nykvist, he who gave us some of the most beautiful visuals in cinema, thanks to his decades-long work with Ingmar Bergman. In his book, Boyer elaborates what Rafelson was looking to create with Nykvist:

“Rafelson meant to explore the possibilities of deep-focus photography even more fully than he had in his earlier films. He wanted a look to this film that not only made use of several distinct visual planes but also allowed for high contrast of color between these planes — something he coined ‘Gregg Toland in color,’ after the famous cinematographer of Orson Welles’ black-and-white 1941 classic Citizen Kane…. “

Together Nykvist and Rafelson talked about avoiding the sepia toning that had become identified with films of the Depression period, of ridding themselves of the art deco trappings of such films…. To begin with, they would shoot in earth tones, avoiding the high colorization of some color cinematography, doing their best to capture the world of [lead characters] Frank and Cora and Nick as the human eye might see it…. Cain’s story was Depression era, one recalls, and there might be something in the lighting to suggest a dreariness of life that could serve to inspire the lethal in us all.” [pp. 79-80]

Rafelson himself spoke about his work with Sven Nykvist when he was interviewed at the Midnight Sun film festival. He first talks about Five Easy Pieces and how he intentionally never moved the camera in all the exterior shots (it was allowed for the interior shots — which of course include the vigorous sex scene where Nicholson literally carries Sally Struthers as they mime the sex act.) Then he discusses his collaboration with Nykvist.

Viewers of the Funhouse TV show will be interested to know that Rafelson was invited to the film festival by Funhouse deity Aki Kaurismaki (read Rafelson’s own description of Aki at the video’s opening) and the great critic Peter von Bagh. The passage about cinematography begins here at 36:37.

The other key behind-the-camera collaborator was David Mamet, who made his screenwriting debut with Rafelson’s Postman. Mamet was already an established playwright but had yet to write anything for film, and so he let himself be cajoled by Rafelson into transforming Cain’s Thirties tale of primal emotion and existential fatalism into a film fit for the Eighties.

The film thus became a stylized version of the book, but the stylization was not the “neo-noir” look that was used in pastiches like Body Heat — instead, Rafelson chose a “duller” palette of colors and communicated the “life on a shoestring” quality of Depression-era existence with sharply defined characters, taut dialogue, and attractive yet memorably bleaker-colored images.

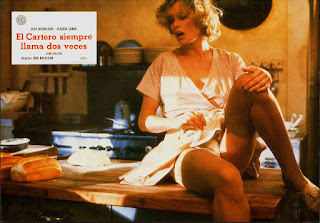

And there was indeed a memorable dose of sex in the film. That’s an element that mainstream American filmmaking now avoids like the plague (in fear that someone will be offended by something they see), but in 1980 (when Postman was shot) the Seventies were still alive in terms of an unflinching attitude toward sex.

The key sequence here, when the film really kicks into gear, is when drifter Frank Chambers (Jack Nicholson) finally loses his cool and attacks the bored Cora (Jessica Lange). It begins with her beating him off, seemingly introducing a rape sequence, but her own primal urges come to the fore when she starts responding to Frank’s animal lust and then the moment that most reviewers doted on, when she stops Frank completely, in order to sweep all of her cooking materials off of the table so they can continue on a flat surface with nothing in their way. (“All right, c’mon, huh? Come on, come on...” Cora beckons.)

This sex sequence is performed with both actors fully dressed — Cora’s blouse is pulled down but not her slip, and Frank has still got everything on. The shots that bring home the immediate and aggressive nature of their coupling come when we see between Frank’s hand between her legs, rubbing feverishly through her panties. She takes away his hand, only to replace it with her own (and then his hand enfolds hers as she touches herself). Here, the Seventies does insert itself [ouch] into the Thirties as we are witnessing Cora experiencing orgasm as she and Frank rut like crazed animals on the kitchen table.

The film contains only a few other sex sequences after this one, but the scene has so imprinted itself on the viewer’s mind (since it erupts after visual inferences have been made to Frank scoping out Cora) that Rafelson’s Postman became known as a “sexy” crime picture. (The phrase “erotic thriller” didn’t come into heavy usage until the late Eighties/early Nineties.) It thus did quite well at the box office and ensured Rafelson was safely back in the biz for at least another few years.

|

| Nicholson, Lange. |

Mamet and Rafelson spend so much time on the legal nuances that the characters of the lawyers (led by Michael Lerner as the defense attorney for Cora and Frank) register as being much, much sleazier than their lustful, murderous clients ever were. This leads to the third act, where it seems possible that Cora and Frank might indeed live happily ever after — but Frank can’t curb his libido, thereby ushering in the film’s oddest sequence (straight from the book) when Frank has a side-affair with a carnival big-cat trainer (Anjelica Huston) and he comes back to Cora, who has a present from the tamer, a large feline, sitting on their bed.

|

| Anjelica Huston. |

Postman brought Rafelson back to his regular practice of spotlighting talented supporting performers. Here, one sees Anjelica Huston affecting a bizarre accent as the animal tamer; Michael Lerner as the ultimate scheming lawyer (who is somewhat of a “hero” since he frees the two leads, whom we both sorta like by that point in the film); even John Colicos as the boorish husband is somewhat sympathetic, since Rafelson loved to let his supporting cast shine.

Much has been made in hardboiled-purist circles of Nicholson being too old for the character of Frank. (He was 43 when he shot the film, and the character in the book is 32.) But this was Jack still in his prime (read: before Terms of Endearment, when he started sailed through films, getting by on his personal charm [and eyebrows] and taking on insubstantial characters in boffo-budgeted multiplex fare). And so his Frank truly is a genuine-seeming character — a seamy guy who clearly has a criminal past but also some relatable tendencies.

The biggest discovery of the film (although she had already been featured in three films, including the sublime All That Jazz and the ridiculous ’76 King Kong) was Jessica Lange. Her Cora is a fully developed character who is fascinating to watch. Like Frank, her instincts are crooked, but she is trapped in her marriage, and thus her trying to get away from her husband and his low-rent diner makes total sense.

|

| The swimming scene in the '46 Postman. |

It seems obvious that Rafelson and Mamet counted on the viewer liking Frank and Cora enough by the end of the film that her death seems sufficient “punishment” to Frank (clearly, her murderous instincts aside, she’s the first positive influence in his adult life). Thus, they took away the frame, which, of course, added yet another level of fatalism to Cain’s storyline (thus his work being beloved in France, well before the Serie Noire came into existence). A modernist touch and one that does somewhat remove the film from strictly being a “crime picture.” (Click the words "Watch on Odnoklassniki" in the embed and watch on the site housing the full film.)

Rafelson didn’t make another feature until 1986. From the early Eighties onward there would be gaps of several years between his films, presumably because (as is evidenced by descriptions in his interviews) he had become a world traveler and preferred his journeys to foreign lands to fighting studio heads to get his personal vision back on movie screens.

One of the rarest items from Rafelson’s rather small output that is hiding in plain sight is the short “Modesty,” which he made in 1981 when he was staying in Paris. The film consists of a young student (Camille Casabianca) interviewing Rafelson (playing himself) and finding out some of his “secrets.”

In the piece he gets average French folk off the streets to recreate the kitchen scene from Postman and discusses how he is never sure when meeting a woman whether she likes him for himself or because he is a director. He shows himself having dinner with the young interviewer and two women who both seem eager to sleep with him. He then visits a parking garage where musicians rehearse and pays them to play a goodbye tune as he goes on a train to some other part of France.

The film is odd but endearing. The oddest element is the interviewer, who looks 14 but was actually 21 when the film was shot. She was indeed a “ringer” — not an ordinary student appearing out of the blue at Rafelson’s doorstep to interview him, but the daughter of the great filmmaker Alain Cavalier (L’insoumis with Delon) and the editor Denise de Casabianca (The Mother and the Whore, The Return of Martin Guerre). Camille did go on to be a filmmaker, but the one credit of hers that will be familiar to American cinephiles is as the screenwriter for her father’s sublime Thérèse (1986).

Rafelson next directed an unusual work for hire. In 1983 he was hired by former Monkee Mike Nesmith (working as a producer) to direct the music-video for Lionel Richie’s “All Night Long.” It was perfectly fine at the time (including some nice oblique camera angles), but like many music videos it’s a time capsule into a time when certain ridiculous things (break dancing, robot dancing) had cultural cache.

Then there was Black Widow (1987), a thoroughly entertaining thriller that had some small traces of Rafelson’s personality in it but could’ve been made by any number of talented directors working in Hollywood in ’87. The film is better than remembered — mostly because it’s harder to remember the tangential bits and pieces (and performers) that end up being “grace notes” that make the film worth rewatching.

|

| Debra Winger, Theresa Russell. |

One of the problems with the film is the fact that it races through some of the early cases, and then settles on showing us the last one in great detail — the husband in that case is played by French actor Sami Frey, best known for starring in Godard’s Band of Outsiders. Frey is good in the role, but his character isn’t all that interesting.

|

| Winger, Sami Frey. |

Those of us who do not need character motivation to be spelled out 100% can forgive plenty of the strange little missteps in Black Widow, including the fact that Theresa Russell’s character is less a chameleon, as is first inferred, than she is a sociopath whose romances with her victims don’t seem convincing in the first place.

The central “driver” of the plot is the obsession that the heroine —a Justice Department data-analyst-turned-detective played by Debra Winger — develops with the “Widow,” but even that is never quite developed to the point where it fully makes sense. Does Winger also have a sociopathic strain and admires the Widow? Does she simply want to solve “the crimes of the decade”? Or does she have a crush on the Widow, as is implied in some brief moments?

In essence, one can still enjoy the film despite its plotline bouncing from one episode to another and not answering the central question about its heroine’s motivation. (The sudden ending, wherein we are deceived, as is the Widow, is oh-so-clever but also seems like the finale of any number of detective TV show episodes.) What makes the film worth seeing, though, is Rafelson’s work with the two leads.

The always underrated Theresa Russell does a wonderful job with her role, as underwritten as it is. (Boyer notes in his book that we never do find out the Widow’s real name — by contrast, in Rafelson’s later Man Trouble a final plot point involves Nicholson’s character revealing his nerdy-sounding real name to his amour.) She is lively and vibrant enough to seem like the kind of woman who could insinuate her way into any man’s lifestyle and become the center of it.

Winger’s role is far more developed in the screenplay, but since her character’s feelings toward the Widow are blurry, she also does miracles with the character, making her a mess of conflicting impulses and an ultimately shrewd detective. Black Widow isn’t “personal” Rafelson, but it is an entertaining thriller, despite its plot holes. (Click the words "Watch on Odnoklassniki" in the embed and watch on the site housing the full film.)

Rafelson’s next film arose out of his love for traveling — and anthropology. First, a side-note about his traveling: in the last interviews he did the topic came up again and again, mostly to explain where he went between films and why there were so few of them (since he lived to be 89, but there are only 11 features from a 34-year career).

The writer for Esquire, Josh Karp, spends a paragraph detailing Rafelson’s wounds and injuries (in something akin to the old “Tom Mix’s injuries” chart). In his teen years, it is noted, Rafelson entered a rodeo in Arizona and broke his coccyx. He “broke both his arms and legs after falling during a riot in India.” He had physical confrontations with several people over the years, to the point where “all of this has left him with steel rods in his spine and one of his arms, a plate in his shoulder, and chronic pain.”

Another interview, conducted in 2019 for The Aspen Times mentions him “trekking Africa and the Amazon alone, finding trouble in far-flung global danger zones.” Then the piece goes on to describe his most recent adventure as of that writing:

|

| Latter-day Bob, ready to travel. |

"'So we got tear-gassed, pepper-sprayed, we’ve got rubber bullets flying on the first f-ing day,' Rafelson recalled.

"A cellphone video shows the chaotic scene, and a crowd parting for Rafelson, using hiking poles on the cobblestone street amid the throng. As he passes through, the youthful crowds break out in applause for him.

"'The only reason why they were applauding was because I was quadruple the age of anyone else in the streets and they saw me every night,' he said. 'They were as young as I was in the ’60s when I marched.'"

In case you think that’s a bullshit story, here’s the footage:

Rafelson disliked being interviewed, but both of the above pieces he was happy to do, since both writers gave him ample space to rhapsodize about his personal favorite of his films, the 1990 adventure Mountains of the Moon. The film was like nothing else he ever made, and he proclaimed it to be the closest to his heart. As of this writing, the best way to obtain it is by buying a used U.S. DVD (make sure to get the “Widescreen edition”) on Artisan or the Spanish Blu-ray.

In the Boyer book, Rafelson is quoted (from an American Film interview) as saying he first read about Sir Richard Burton (the explorer from the 19th century) when he studied anthropology and then came across his translations of erotic texts. He read about Burton’s explorations later on and clearly looked to him as a personal hero: “Of course, I do a substantial amount of traveling and I learned a lot about how to do it from him…. He would settle with various tribesmen for a period of time and then go onto the next civilization. He was a cultural thief in a way; he would steal what he thought was profound and move on, and I do some of that.” [pp. 95-96]

|

| Patrick Bergin as Sir Richard Burton. |

He shot the film in 10 countries over three months for less than $15 million, and the miraculous part is that the film does look “epic” in its visuals. This was thanks to Rafelson’s top-notch work with cinematographer Roger Deakins (1984, numerous Coen bros titles). The film is indeed as “big” as Rafelson’s best Seventies movies were “small,” but the third act is about the basic emotions of envy, betrayal, and regret.

The narrative of Mountains is more straightforward than the plots of Rafelson’s thrillers, but it still has its share of twists and turns. The first act is comprised of the first meeting of Burton (Patrick Bergin), an explorer with an insatiable thirst for knowledge about other cultures, and Speke (Iain Glen), a hunter whose travels are motivated by his desire to shoot big game in remote locales. The two head out on an expedition to find the source of the Nile River and fail miserably — they are the only survivors of their party.

The second act, which takes up the bulk of the film (an hour out of 2:15), chronicles their second expedition to find the Nile’s source. This time, both men emerge with a theory they are certain is the answer — Speke believes the Nile begins at Lake Victoria, while Burton believe the River is the product of a basin of lakes.

The third and most important act charts how the two friends fell out — Speke’s publisher (Richard E. Grant) convinced him that Burton had belittled him in the official report of the first expedition. Burton is befriended by David Livingston (of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” fame) and a debate is set up between Burton and Speke. The surprising finale finds one of the ex-friends acting rashly out of a regained respect for the other.

|

| Iain Glen and Bergin. |

A great example of a sequence that could’ve been in a classic adventure picture is one where Burton volunteers to scare away two female lions who are about to pounce on a trapped slave. He does so successfully but is unaware of a male lion lying in wait on his flank. Speke, an expert marksman, takes out the male lion just as it leaps at Burton.

A scene that reminds us that we’re watching a modern adventure movie comes when the crippled Burton, walking on crutches, urgently summons Speke, who wonders what the matter is. Moving quickly behind a rock formation, Burton hollers, “I can’t get my trousers down — I need to shit!” Errol Flynn and Stewart Granger never, ever acknowledged bodily functions in their macho adventure flicks.

Although working in a completely new genre, Rafelson still let his supporting actors get their big moments. Fiona Shaw plays Burton’s wife, who has to spur him back into action when his friend’s betrayal causes him to withdraw from the world.

Delroy Lindo has a featured role as the slave of a tribe who is befriended by Burton. He ends up being trapped again as a slave because he trusts Burton, and Burton risks his life trying to save him, shouting at one point in desperation, “He’s my friend!”

And Richard E. Grant, always immaculate as upper crust prigs, is the cad who drives a wedge between Burton and Speke.

Glen is quite good as Speke, but Bergin clearly has the showier role as Burton. His work in the picture is so good because it seems that he is adding things to his portrayal that come from Burton’s other, non-Nile pursuits (in a very busy life that found the polymath being not only an adventurer but also an author, translator, and a lover of languages [who spoke 29 of them]).

|

| Rafelson directs Mountains. |

Among the film’s fans were Alexander Payne and Francis Coppola, who, when asked by Josh Karp in the 2019 Esquire profile if Rafelson deserved a Lifetime Achievement Oscar, said “Such an award would be appropriate if his only single film had been Mountains of the Moon.” Rafelson touted the film in every interview he did and requested that film programmers show Mountains when they paid tribute to his work, rather than the commonly seen Five Easy Pieces.

Rafelson was so “high” on his great experience making the film that he published an article about the production. True to the one-off oddness of the whole enterprise, his piece appeared in Elle in the April 1990 issue.

|

| Delroy Lindo, Bergin. |

“In the Amazon, I tried to take some Polaroids of a tribe not previously in contact with whites. They looked at the photos, then threw them aside. They had no mirrors, and therefore no reference points for images. However, they liked the colors of my shirt. Fortunately for me. I later found out they had killed two Peruvians in military khaki….”

“Unlike Burton, I have no other language. (He mastered 24 [sic].) He had destinations in mind. I have tickets. He wrote books, translated Arabic poetry, was a brilliant swordsman. Swinburne thought he looked like the devil. I carry a Swiss Army knife and only succeed in looking ridiculous. But in remote places it helps. Don’t look serious. Soldiers look serious. Anthropologists and missionaries look more so. If tribal people weave, then better to be adorned in bright, handwoven threads. A Pakistani shirt, pantaloons. A Rasta cap. Banana Republic can kill you.” [Boyer, pp 123-24, from “Director’s Diary,” Elle April ’90, p. 82]

Another great scene. (Note: The copies of the film that are “above ground” online are awful. One is best served obtaining this film on disc.)

Rafelson’s next film was thought of by critics and yours truly as his worst. In rewatching all of his features to write this, I found that Stay Hungry (discussed in Part 1) was actually a far clunkier comedy, Blood and Wine (see below) went very astray, and Poodle Springs (ditto) was a flat-out work for hire with barely any traces of Rafelson’s style.

|

| Posing for the poster: Jack and Ellen. |

In his book on Rafelson, Boyer goes through the many steps that it took to get the film made. Eastman wrote the screenplay in the early Seventies, with the intention of starring Nicholson in the role he eventually played, a guard-dog trainer and general con man, and Jeanne Moreau as an insecure opera diva. She had hoped the film would be her directorial debut, but that idea was scratched when another film she scripted starring Nicholson (The Fortune) failed at the box office.

The film then nearly got made in the Eighties with Jonathan Demme directing Nicholson and Diane Keaton, and then Robert De Niro and Jessica Lange. Al Pacino was then on the hook for the male lead, but he demanded rewrites and so a deal was worked out so that Jack could do the film “around” the shooting dates for his own directorial effort, The Two Jakes (1990).

Eastman said that the film was originally written with the opera singer as the star, but when Nicholson came onboard, his character had more prominence. He also made more money than anyone else on the production, since he was a superstar by the Nineties and commanded anywhere from $7 to $10 million per picture – and, despite his loyalty to both Rafelson and Eastman, he couldn’t lower his price for their project, since that would mean he’d have to take much less dough for future films.

|

| Ellen Barkin, Beverly D'Angelo, Veronica Cartwright. |

Here, again, Rafelson assembled an excellent cast and watching them is the strongest pleasure to be had from Man Trouble. Nicholson surprisingly underplays his role at points, and Barkin is charming, although pretty oddly cast as an opera star. Also featured in the picture are Beverly D’Angelo, Veronica Cartwright, Michael McKean, David Clennon, and Paul Mazursky. The nicest piece of stunt casting is that there’s a much-discussed crooked millionaire character who isn’t seen for two-thirds of the picture, but it is then revealed to be played by Nicholson’s longtime, Laker-watching friend, Harry Dean Stanton.

|

| Awaiting the Lakers season pass: Jack and Harry Dean. |

After Man Trouble, Rafelson made the first of two “erotic” short films for German producer Regina Ziegler (who worked in conjunction with German television). “Wet” (1994) is a trifle, scripted and directed by Rafelson, that concerns a nebbishy bathtub salesman who has a good-looking customer (Cynda Williams) come on to him.

Like the other entries in the Ziegler-produced series (made by Ken Russell, Susan Seidelman, and Melvin Van Peebles), we realize that this “shortie” (Rafelson’s term for it) is meant to funny and not all that erotic. We also sense that the short is moving toward a comic payoff. (Here it’s that the woman did all this to acquire a top-of-the-line bathtub for free.)

|

| Cynda Williams in "Wet" (short). |

|

| "Porn.com" (short). |

In an effort to be comprehensive I mention both shorts, but they are more curiosities than important (or even erotic) exercises by Bob R.

*****

Rafelson’s next film, Blood and Wine (1996), was another thriller. Giving it a rewatch one finds it’s not as bad as remembered, but it’s also too long for the strict confines of the plot, and the third act lags incredibly, even while the characters are feverishly double-crossing each other.

The plot revolves around a wine salesman (Nicholson) in need of $ who plots with a British safecracker (Michael Caine, with hair dyed back — referenced in the plot — and a consumptive cough) to rob one of his rich clients of a priceless necklace. The salesman is carrying on with the nanny (Jennifer Lopez, before her music career took off) who works in the home of the rich family that own the necklace.

|

| Joking about the denial of age: Jack and Michael. |

One of the film’s two scripters, Alison Cross, has had a pretty solid career writing for television, and when it reaches its last third Blood and Wine does indeed play like a TV-movie (or, to be kinder, a made-for-cable production). The film does have a suitably fatalistic ending, which makes it more like a theatrical feature than a telefilm, but the emphasis on the family unit becoming homicidal and the contrivances in the plot (such as having Lopez’s character becoming involved with both stepfather and stepson) brings us back to the world of fast-paced but still overly talkative television.

|

| Jack trips the light fantastic with JLo. |

The failed marriage of Nicholson and Davis’ characters is the most galvanizing part of the film, since Davis is a powerful performer who can make even the smallest of roles shine. Caine is obviously an incredibly gifted scene-stealer, but his character here is simply a collection of numerous tics (including the dyed hair, an incessant cough, and Caine’s own cockney accent). Lopez and Dorff acquit themselves nicely, but one is simply fed up with their characters by the last third of the film.

|

| Judy Davis in Blood and Wine. |

Nicholson is back in quiet mode here for most of the picture, which is a blessing (by this point in the Nineties, he knew he could give a “Jack performance” and just sail through certain films). He does melt into the character, who is a loser circulating in a winner’s world and a seedy playboy who is trying to bank on his old charm.

|

| Rafelson with Nicholson and Caine. |

The hands-down best scene comes when Davis and Dorff are paralyzed in a car that has flipped over, and Nicholson runs to the car and enters it through the back window — not to rescue them, but to find the necklace. The amorality of his character is beautifully established at this moment, and one wishes the film were as coherently crooked throughout and not just dependent on several coincidences. (Click the words "Watch on Odnoklassniki" in the embed and watch on the site housing the full film.)

Poodle Springs (1998), the next feature directed by Rafelson, was another “for hire” affair. It was a well-budgeted HBO production that was adapted by the Robert B. Parker novel of the same title, which was his attempt to write the last Raymond Chandler-Philip Marlowe book (which existed as a few chapters and an outline written by Chandler before his death).

Set in the early Sixties, it shows us Marlowe (James Caan) married to a socialite (Dina Meyer) and still working as a P.I. As per his past adventures, he tracks a seemingly innocuous small crime and finds behind it a web of corruption. Here, the innocuous crimes involve a bigamist photographer (David Keith) and the web of corruption is controlled by a millionaire (Brian Cox) who wants to “move” a California town into Nevada through redistricting.

The idea here is to depict an older, still confident but more liable to falter, Marlowe, who is also in danger of becoming respectable because of his new wife. The plot contains characters that remind one of previous Chandler creations, especially a psychotic socialite (Julia Campbell) who grew up in the same circles as his wife. Tom Stoppard wrote the script, which seems to be modeled on all the preceding Marlowe films, especially The Big Sleep and the two Chandler adaptations starring Robert Mitchum. It also contains a particularly chipper and especially happy ending, which is depressing coming from the man who gave us Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens.

Thus, Poodle Springs is mindless fun for those who just want to see another adventure of the ultimate hardboiled detective. The problem is that Marlowe, as written by Chandler and played by Bogart and Mitchum, was a cut above the average private dick in hardboiled crime fiction. He was a modern knight-errant who had a code of honor and was proud of his detective work (although still capable of falling for the wrong dames over and over).

|

| Mike Hammer in the guise of Marlowe: James Caan. |

The film ends with a neat little joke — the ridiculously optimistic finale includes a glimpse at a newspaper in Marlowe’s office that boasts the headline “Kennedy in Dallas.” So, Marlowe’s hopeful future includes the late 1960s, a time when the old-school private eye is no longer needed. (And was unsuccessfully updated in the James Garner Marlowe and completely transformed in Altman’s brilliant The Long Goodbye — a film that had a much clearer outlook on the post-1950s Marlowe than Poodle Springs.) (Click the words "Watch on Odnoklassniki" in the embed and watch on the site housing the full film.)

Thankfully, Rafelson directed one more feature before he decided to pack it in and retire for good — and it’s a good solid thriller that puts Blood and Wine and Poodle Springs in the shade. No Good Deed (2002) was financed by independent American companies and a German one (and shot in Montreal). It was barely released in theaters and went out of print very quickly on disc. (It can be found on a streaming service, but you’d be putting good cash in Bezos’ pocket.)

The film is superior to its two predecessors, with taut scripting making the crazier contrivances of the plot seem plausible. No Good Deed is a chamber piece spun off of a short story by Dashiell Hammett featuring “the Continental Op,” “The House on Turk Street,” by two scripters, Christopher Canaan and Steve Barancik. Perhaps both were responsible for making the film such a model of compact hardboiled storytelling, but one can more easily point to Barancik, as he wrote the memorable Nineties noir The Last Seduction (1994).

The always great Samuel L. Jackson plays a cop with a longing to be a classical cellist — that seems like an odd place to start a movie, but every detail here is compounded and returned to (except the original premise of his searching for a missing person; by the middle you realize the initial premise doesn’t much matter). Jackson promises to help out a friend, and so, while he protests that he works in the grand theft auto division of the police, he agrees to look for her daughter, who has run away with a creepy gentleman.

Because of his charitable demeanor (and the kind of coincidence that often sets the best crime films in motion), he winds up in a house where a group of crooks are planning a bank robbery. He remains tied up for a good deal of the film, but he becomes privy to the entire plan for the heist and the fact that the “black widow” among the bunch, a sexy Russian (curiously named “Erin”) played by Milla Jovovich, has seduced each male member of the group and has made plans with each one to run away with them and all the loot.

Milla also seduces Jackson, since they do have something in common (a shared love of performing classical music), and she understands early on that he is far smarter than at least two of the heist group and is the equal of the remaining one (Stellan Skarsgård), who is the boss of the outfit.

Her seduction of Jackson is presented as a classic meet-cute moment (in which it’s joked about that Jackson is actually free of his bonds for a moment, but he “owes” her for helping him obtain insulin for a diabetic episode he had). The two "play" the cello together, with Sam encircling her and showing her the chords involved in playing a certain piece.

|

| Jackson, Jovovich. |

A very small ensemble of performers has central roles here, but thankfully Rafelson’s final film included some scene-stealing supporting performances. Grace Zabriskie and Joss Ackland are the aged couple (quite amorous for their age) who are supposed to fly the crooks to safety after they pull the bank job. Doug Hutchinson ably plays the most brutal (and dumbest) of the crooks, who is a foil to Skarsgård’s character, a refined criminal whose only weakness is (take a guess) Jovovich.

|

| Jovovich, Skarsgård. |

Those of us who really love Rafelson’s best films can lament the fact that he only made 11 features and retired from filmmaking at the young (for him, certainly) age of 69. But we can count our blessings that he went out on a great note with a well-constructed and suspenseful “small movie” that lingers in the memory. (Click the words "Watch on Odnoklassniki" in the embed and watch on the site housing the full film.)

Thanks to Paul Gallagher and Jon Whitehead of the Rarefilmm site for help finding some of the films.

_630_340_90.jpeg)