Before I sink into Williams’ best

performances, let me briefly touch on the beginning of his career on TV and two

of the more memorable recent appearances of what seemed to be “the real Robin.”

Williams appeared on two short-lived NBC variety series in 1977. The most notable is The Richard Pryor Show, which was notoriously censored by the network and then canceled. The other one-season wonder was the resurrection of Laugh-In. This little chunk of the show includes Frank Sinatra and Jilly, Cindy Williams, Flip Wilson, and the new cast of zanies (featuring both Robin *and* the equally frenzied Lenny Schultz!).

Williams appeared on two short-lived NBC variety series in 1977. The most notable is The Richard Pryor Show, which was notoriously censored by the network and then canceled. The other one-season wonder was the resurrection of Laugh-In. This little chunk of the show includes Frank Sinatra and Jilly, Cindy Williams, Flip Wilson, and the new cast of zanies (featuring both Robin *and* the equally frenzied Lenny Schultz!).

Another nugget of Robin as a comic

actor, this time on the absolutely brilliant America 2-Night

(1978). Here he plays a small-town gigolo interviewed by Barth Gimble (Martin

Mull) and Jerry Hubbard (Fred Willard).

The contrast between early and

“later” (read: recent) Williams is, of course, incredibly sad, since, as was

noted in the Guardian piece that I linked to in part one of this entry,

when he was revealing his inner self to interviewers he would get very quiet

and incredibly serious. His sense of humor was still there, but it was a

grimmer kind of humor, in which he tended to laugh at himself or at the

inevitability of certain situations.

This was most prevalent in his interview with Marc Maron on the WTF podcast. The interviewer was a very

important one for Maron, as Williams was his biggest-name guest to that date

and the episode cemented Marc’s role as a seeming “therapist” figure in his

interviews (albeit a therapist who mentions his own addictions and problems at

length). The result is a very touching and genuine interview that did indeed

introduce us to the “real” Robin.

The most moving instance of this same quiet, reflective Robin appeared in the recent (2012) episode of Louie in which he and Louis CK (both playing themselves) meet at the funeral of a much-loathed comedy-club owner — a funeral at which they are the only attendees. It is a beautiful piece of work that is a testament to both LCK’s writing/directing and Robin’s acting:

The most moving instance of this same quiet, reflective Robin appeared in the recent (2012) episode of Louie in which he and Louis CK (both playing themselves) meet at the funeral of a much-loathed comedy-club owner — a funeral at which they are the only attendees. It is a beautiful piece of work that is a testament to both LCK’s writing/directing and Robin’s acting:

*****

But now, onto Williams’ film work, the crème de la crème in my estimation. Setting aside a bit part in the sketch comedy film Can I Do It ‘Till I Need Glasses? (1977) — which was of course rereleased when he became a TV star — Williams started at the top, as the star of Robert Altman’s large-scale, big-budget, ultra-imaginative (and often utterly crazy) Popeye (1980).

But now, onto Williams’ film work, the crème de la crème in my estimation. Setting aside a bit part in the sketch comedy film Can I Do It ‘Till I Need Glasses? (1977) — which was of course rereleased when he became a TV star — Williams started at the top, as the star of Robert Altman’s large-scale, big-budget, ultra-imaginative (and often utterly crazy) Popeye (1980).

The film was trashed by critics when

it came out and was reported to have been a flop at box office (although Altman’s

obits noted it did quite well, rating as his second highest-grossing film

behind M*A*S*H). In recent years it has been reappraised and

now has a cult following, which includes Paul Thomas Anderson, who used a

Popeye song from the film in Punch Drunk

Love.

My take on the film is that it is a visual marvel that is also two-thirds of a great picture. I am a major Altman worshipper, but Popeye is one of that small group of his films that peter out in the last third — A Perfect Couple is the best example of this “almost perfect” type of film.

The last third of the picture devolves into a chase scenario (and then a fight, and then shtick with an octopus) — a chase at the end of a farce nearly always being a sign that a scripter gave up. In this case the scripter was the great Jules Feiffer, and the “descent” into endless frenzy was reportedly the result of the wild mood on the set (which was located on the island of Malta and was populated by well-medicated individuals); if I remember correctly, it’s been noted that the production ran out of money to get the end of the script shot.

My take on the film is that it is a visual marvel that is also two-thirds of a great picture. I am a major Altman worshipper, but Popeye is one of that small group of his films that peter out in the last third — A Perfect Couple is the best example of this “almost perfect” type of film.

The last third of the picture devolves into a chase scenario (and then a fight, and then shtick with an octopus) — a chase at the end of a farce nearly always being a sign that a scripter gave up. In this case the scripter was the great Jules Feiffer, and the “descent” into endless frenzy was reportedly the result of the wild mood on the set (which was located on the island of Malta and was populated by well-medicated individuals); if I remember correctly, it’s been noted that the production ran out of money to get the end of the script shot.

When the film is working, it’s a cartoon come to life that benefits not only Altman’s unerring eye for casting — Shelley Duvall was the one and only choice for Olive Oyl — but his love of depicting unusual communities in his films. The other sublime aspect is the collection of songs by Harry Nilsson, which perfectly establishes the light and lively tone of the film.

Robin does a wonderful job as Popeye, naturally reveling in the character’s tossed-off asides and unique mode of cursing.

After Popeye came

Williams’ first lead dramatic role, as T.S. Garp in the excellent movie

adaptation of World According to Garp (1982). Robin

incarnates Garp with depth and nuance — a far cry from his

everything-and-the-kitchen-sink-too approach to comedy.

As I noted in the first part of this piece, the film works beautifully because it points the viewer back to

the book. Like Slaughterhouse-Five (1972), it’s an example

of George Roy Hill tackling an episodic novel and producing an excellent film

(without Slaughterhouse’s only flaw — a really flat lead

actor).

The ensemble cast is all terrific — Glenn Close was never better and John Lithgow injected the perfect note of sincerity to his eccentric role. But, in the final analysis, the film rests on Williams. And, as often happens when an artist or entertainer dies, certain moments from their work acquire an added poignancy.

The ensemble cast is all terrific — Glenn Close was never better and John Lithgow injected the perfect note of sincerity to his eccentric role. But, in the final analysis, the film rests on Williams. And, as often happens when an artist or entertainer dies, certain moments from their work acquire an added poignancy.

A lot of the movie comedies Robin

starred in missed the mark. One that is half a good movie is The

Survivors (1983). Michael Ritchie functioned as a sort of mini-Robert

Altman in the Seventies, making perceptive films about the American Dream that

were excellent time capsules that also happened to explore timeless issues — The

Candidate, Smile, and Semi-Tough

being the three best examples.

The Survivors finds William teaming with Walter Matthau in a satire on the survivalist movement. The film makes very good points about America’s obsession with guns and militarism, until it basically becomes just a kooky, crazy comedy about Robin’s character’s personal war against a crook (Jerry Reed).

The Survivors finds William teaming with Walter Matthau in a satire on the survivalist movement. The film makes very good points about America’s obsession with guns and militarism, until it basically becomes just a kooky, crazy comedy about Robin’s character’s personal war against a crook (Jerry Reed).

One of Robin's finest performances

is in a film that most have overlooked, a PBS production based on a Saul Bellow

novel called Seize the Day (1986). He plays a completely

normal guy, a down-on-his-luck salesman in Fifties NYC. He needs dough for his

wife and kids (and his mistress, who wants him to marry her). As the film moves

on, he descends in a downward spiral that ends with a very memorable finale.

The film is one of those perfect

“small movies” that evokes a place and time while also showcasing a great

ensemble of actors. Director Fielder Cook reproduces the Fifties in beautiful

detail — not that big a surprise, as he spent that period directing landmark TV

dramas like Rod Serling's “Patterns.”

The incredible supporting includes Joseph Wiseman (as Williams' dad, another classic portrait from Wiseman of an old-fashioned Jewish gentleman), Jerry Stiller (in a scene-stealing role as a con artist), Tony Roberts, John Fiedler, William Hickey, Jo Van Fleet, and Fyvush Finkel.

The film qualifies as a great discovery for those who like Williams as an actor, but have only seen him in mainstream Hollywood fodder.

The incredible supporting includes Joseph Wiseman (as Williams' dad, another classic portrait from Wiseman of an old-fashioned Jewish gentleman), Jerry Stiller (in a scene-stealing role as a con artist), Tony Roberts, John Fiedler, William Hickey, Jo Van Fleet, and Fyvush Finkel.

The film qualifies as a great discovery for those who like Williams as an actor, but have only seen him in mainstream Hollywood fodder.

Awakenings (1990)

was a happy convergence of compelling subject matter, two great lead

performances, and surprisingly subtle direction by Penny Marshall. The oddest

thing about the film, trivia-wise, is that it starred the two men who hung out

with John Belushi on the night of his overdose and was directed by the woman he

briefly left his wife for.

De Niro is in the spotlight giving the more broadly drawn performance (this being the time when every De Niro performance was still worth seeing — before the dry rot and the countless bad movies came along), but Williams matches him perfectly, playing the button down real-life doctor/author Oliver Sacks. Here is a wonderful scene featuring Williams, from the end of the movie.

De Niro is in the spotlight giving the more broadly drawn performance (this being the time when every De Niro performance was still worth seeing — before the dry rot and the countless bad movies came along), but Williams matches him perfectly, playing the button down real-life doctor/author Oliver Sacks. Here is a wonderful scene featuring Williams, from the end of the movie.

The Fisher King

(1991) is possibly Williams' best work on-screen. The film remains for me one

of Terry Gilliam's best films, although it is not a traditional “Terry Gilliam

film” (read: a project he instigated and/or co-scripted). It contains a

beautiful fusion of everyday reality and the kind of lyrical imagery that

Gilliam produces at his best.

The entire cast is terrific, with

Jeff Bridges giving a characteristically terrific lead performance and Mercedes

Ruehl stealing the film as his very down-to-earth girlfriend (she won a Best

Supporting Actress Oscar for her work here). Each piece of the puzzle fits

perfectly, with Williams being perfectly cast as a professor who went insane

and became homeless when his wife was killed in front of him.

The palpable sense of tragedy that Robin was able to conjure is central to his character, but Fisher King is not a flat-out drama — his character actually belongs more to the “charming mental patient” portrait gallery that appeared in the Sixties and early Seventies (with Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment and King of Hearts being prime examples). The film is both a character study and a memorable love story.

Here Williams' character meets his object of obsession, an incredibly mousy young woman played to perfection by Amanda Plummer:

The palpable sense of tragedy that Robin was able to conjure is central to his character, but Fisher King is not a flat-out drama — his character actually belongs more to the “charming mental patient” portrait gallery that appeared in the Sixties and early Seventies (with Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment and King of Hearts being prime examples). The film is both a character study and a memorable love story.

Here Williams' character meets his object of obsession, an incredibly mousy young woman played to perfection by Amanda Plummer:

A disturbing and touching breakdown

scene in which Robin's character loses it entirely as Bridges tries to talk to

him about his real identity, and his enemy, “the Red Knight” appears in Central

Park:

One of the film's most memorable and

gorgeous scenes occurs when Williams pursues Plummer through Grand Central

Station. Oddly, I had remembered this as a piece done in period costume. It

isn't, but it is a slice of everyday reality transformed into radiant romantic

fantasy by Gilliam:

Another unfairly overlooked film

starring Williams is Being Human (1994), directed by

Scottish director Bill Forsyth (Gregory's Girl,

Local Hero). It's an incredibly ambitious film that tracks

one character throughout different historical eras, five in all.

It's a bumpy ride that seems without a destination when the film finds Robin as a slave in Imperial Rome and as a Scottish traveler in Italy. By the fifth and final episode, though, it all becomes clear: his character is just an Everyman looking for a pair of comfortable shoes and trying to figure out how to reclaim the women and children he kept abandoning in his previous lives. His interactions with his children in a long beach scene at the end of the picture seem wholly genuine and very moving.

The whole film can be found here; this is the trailer:

It's a bumpy ride that seems without a destination when the film finds Robin as a slave in Imperial Rome and as a Scottish traveler in Italy. By the fifth and final episode, though, it all becomes clear: his character is just an Everyman looking for a pair of comfortable shoes and trying to figure out how to reclaim the women and children he kept abandoning in his previous lives. His interactions with his children in a long beach scene at the end of the picture seem wholly genuine and very moving.

The whole film can be found here; this is the trailer:

As the Nineties moved on, I began to

“detach” as a fan of Robin's work as an actor just as I had from his comedy in

the early Eighties. This was the result of having seen Hook,

Flubber, Toys, and

Jumanji — all perfectly crafted kiddie movies that didn't do

a damned thing for me. Williams continued to star in many, many features, make

unbilled cameos in other movies, and do voices for cartoons.

Thus I wound up stupidly avoiding What Dreams May Come (1998), one of the best-loved of Williams' dramas, a kind of “Twilight Zone” afterlife saga based on a novel by iconic “Zone” scribe Richard Matheson. The picture is a heavy tearjerker that somehow never gets too Spielbergian (read: shamelessly mawkish) because there is an overload of imagination at work throughout.

Thus I wound up stupidly avoiding What Dreams May Come (1998), one of the best-loved of Williams' dramas, a kind of “Twilight Zone” afterlife saga based on a novel by iconic “Zone” scribe Richard Matheson. The picture is a heavy tearjerker that somehow never gets too Spielbergian (read: shamelessly mawkish) because there is an overload of imagination at work throughout.

The plot can best be summarized as “Orpheus in reverse,” as Robin's character dies, then tries to find his wife in the afterlife after she commits suicide (to make matters even more heavily, heavily dramatic, their kids died years before them). On paper I would run far, far away from this kind of plotline — especially with the added incentive of “state-of-the-art CGI effects” (state of the art for '98, that is) — but Dreams examines notions about death and “where we go” in a way that satisfies even a nonbeliever like myself.

For one of the most memorable scenes is when Williams finds himself in an afterlife that is actually a newly done oil painting, with the presumption being that art really is the stuff of life. The other notion that the picture explores — which of course acquired another level of sadness after Robin killed himself — is the idea that suicides are banished to hell. Here the notion is that good people who commit suicide (in this case Williams' wife, played by Annabella Sciorra) wind up in Hell because they can't forgive themselves.

The film is a bit uneven, but as with Being Human, its sheer crazy ambition makes it worth watching, especially for those looking for a mostly sad, but ultimately hopeful, love story (with a very odd cameo by Werner Herzog at 1:50 here). A favorite scene:

2002 might have been the most

interesting year in Williams' movie career, for in that one year he starred in

three films in which he played the villain — and he was a damned good villain.

The first of the trio is One Hour Photo (2002), a “small movie” that has elements of a crime thriller, but is ultimately a super-low-key character study. Robin is incredibly good as the lead character, a psychotic photo developer who has developed an obsession with a local family. We are both sympathetic to, and creeped out by, his character throughout the picture, and it's a very lonely, lonely piece:

The first of the trio is One Hour Photo (2002), a “small movie” that has elements of a crime thriller, but is ultimately a super-low-key character study. Robin is incredibly good as the lead character, a psychotic photo developer who has developed an obsession with a local family. We are both sympathetic to, and creeped out by, his character throughout the picture, and it's a very lonely, lonely piece:

Death to Smoochy (2002)

is a very dark comedy directed by Danny DeVito that is (again!) half of a great

movie. The first half sketches the characters — most importantly a moronically

naïve children's entertainer (Edward Norton) and the man he replaces, a

foul-mouthed, completely nasty kiddie show host played by Robin.

The script was written by Adam Resnick, the co-creator of the brilliant Chris Elliott show Get a Life and the only Elliott vehicle, the sublimely silly Cabin Boy. Here the characters are similarly brusque and cartoonish, but the picture sadly loses it in the second half and resolves with a race against time — the usual sign (see above, re: Popeye) that a comedy has hit the wall. Still in all, Williams is great as the seriously nasty “Rainbow Randolph.”

The script was written by Adam Resnick, the co-creator of the brilliant Chris Elliott show Get a Life and the only Elliott vehicle, the sublimely silly Cabin Boy. Here the characters are similarly brusque and cartoonish, but the picture sadly loses it in the second half and resolves with a race against time — the usual sign (see above, re: Popeye) that a comedy has hit the wall. Still in all, Williams is great as the seriously nasty “Rainbow Randolph.”

The final 2002 film in which

Williams played the villain is Insomnia (2002), a

cat-and-mouse crime thriller that finds L.A. cop Al Pacino in a small Alaskan

town trying to apprehend psycho-killer Robin.

Director by Christopher Nolan (he of

the “thinking man's action thrillers”), the film is extremely long and contains

a very mannered performance by Pacino as “the drowsy detective” (see, this cop

ain't used to the sun being out all night, so he never gets any sleep and just

keeps moving around like he's in a dream or somethin'....).

Williams is very menacing, perhaps because he plays the character in such a laidback fashion. We don't see him in person until the film's second half, and even there he is mostly present in two-character scenes with Pacino, wherein he outshines our sleepy-boy by simply underplaying his part. Robin brings to mind Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train, but with a sweeter voice and demeanor — making him all the more scary.

Fun trivia fact: one of the Alaskan cops is played by Paul Dooley, who was of course Wimpy to Robin's Popeye in the Altman film.

Williams is very menacing, perhaps because he plays the character in such a laidback fashion. We don't see him in person until the film's second half, and even there he is mostly present in two-character scenes with Pacino, wherein he outshines our sleepy-boy by simply underplaying his part. Robin brings to mind Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train, but with a sweeter voice and demeanor — making him all the more scary.

Fun trivia fact: one of the Alaskan cops is played by Paul Dooley, who was of course Wimpy to Robin's Popeye in the Altman film.

In many of his interviews, Robin

noted that he fell off the wagon in 2003. He went into rehab in 2006, had heart

surgery in 2009, and challenged himself with his first starring role on

Broadway in 2011 (I do wish I had seen that). A few weeks before his death he

checked himself back into rehab for what he called a “tune-up.” It's

interesting to note that his filmography during this period is still as

vigorous as it ever was, but the films were mostly pretty awful.

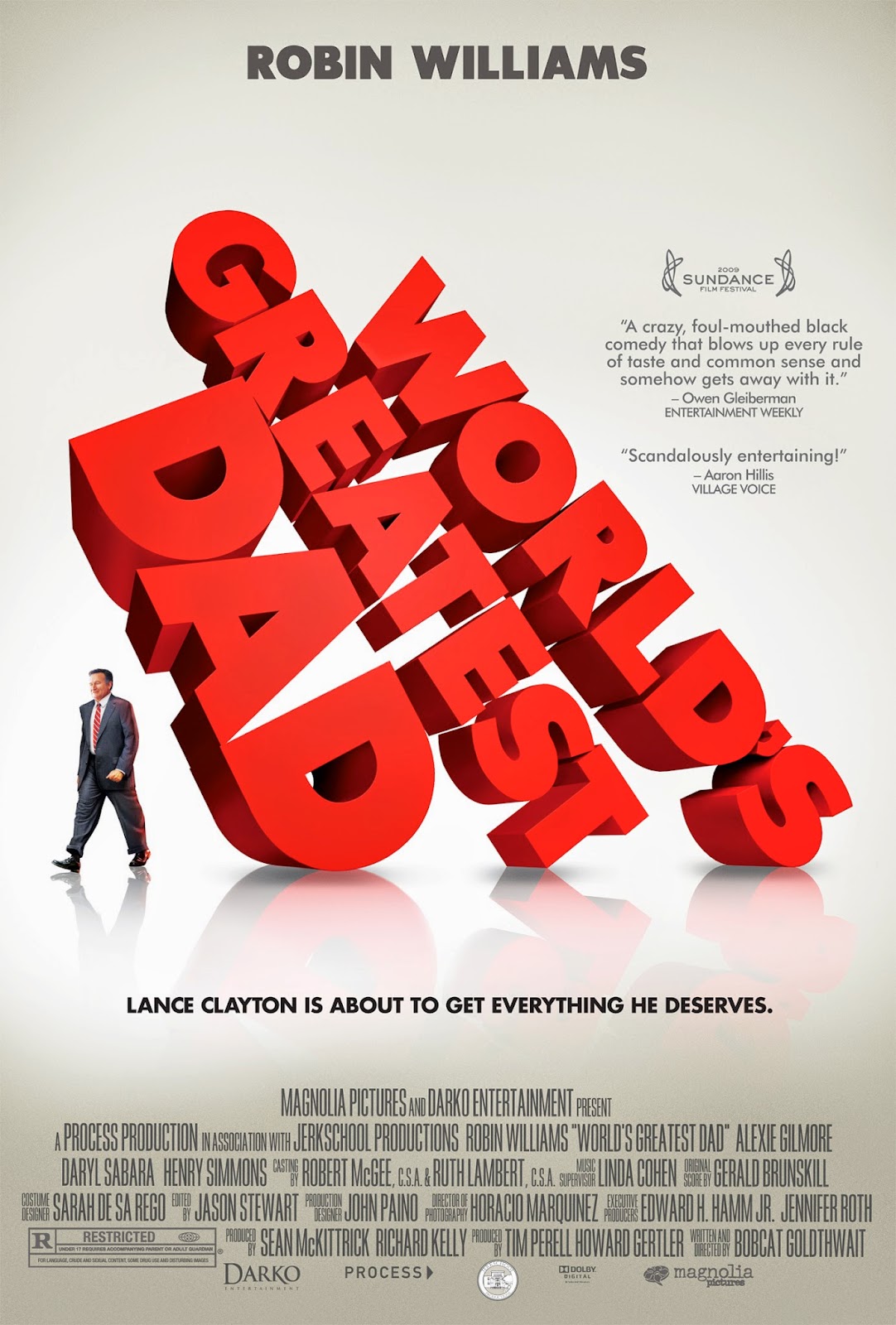

One major exception is Bobcat

Goldthwait's pitch-black comedy World’s Greatest Dad (2009).

Williams plays the father of, to put it plainly (and to quote the film’s

dialogue) a teenage “douchebag” who dies of auto-erotic asphyxiation. He cleans

up the boy's body, and in an echo of Robin's own death, makes the death scene

look as if his son hanged himself. He also writes a tortured suicide note and

later a diary, making his son into a persecuted but big-hearted humanitarian.

A pungent satire of both the gullibility of the American public and the “grief industry,” the film is very funny and extremely nasty towards its targets. Its fit in quite nicely with Bobcat's preceding film, the very funny Sleeping Dogs Lie (2005), another modern American morality play with a sting in its tail, and the absolutely terrific dark comedy God Bless America (2011).

A pungent satire of both the gullibility of the American public and the “grief industry,” the film is very funny and extremely nasty towards its targets. Its fit in quite nicely with Bobcat's preceding film, the very funny Sleeping Dogs Lie (2005), another modern American morality play with a sting in its tail, and the absolutely terrific dark comedy God Bless America (2011).

Of course the film received “news” coverage when broadcasters and Net-gossip sites were looking for sequences in Williams' films that involved suicide. The fact that Robin had appeared in a film on this topic was labeled “shocking” in the click-bait write-ups, but the film ends with a sort of fascinating “purification” sequence and has a very simple message: people are who they are, no matter what happens to them. The celebrity-making machinery of the media moves lightning-fast and is often based on nothing more than a bunch of lies.

Fun fact trivia: Bobcat notes in

this interview (at 5:20) that he wrote the leading role in the film for Philip Seymour Hoffman and initially asked Robin to appear in a smaller part in the

film.

*****

The only way to end this tribute to Robin is to spotlight his relationship with the quick-witted comic genius who made him laugh like crazy, Jonathan Winters. Winters also suffered from depression and was a recovering alcoholic. He never ended his own life, but comparisons of the two men are ultimately faulty, since they both came from different backgrounds, were of different age groups, and used their “madness” in very different ways in their comedy.

Perhaps the best footage of Jonathan cracking up Robin, and then the two trading odd improvs, is this outtake from a 1986 60 Minutes interview. Also wonderful is this goofy little sketch from Winters' 1986 cable special On the Ledge:

The only way to end this tribute to Robin is to spotlight his relationship with the quick-witted comic genius who made him laugh like crazy, Jonathan Winters. Winters also suffered from depression and was a recovering alcoholic. He never ended his own life, but comparisons of the two men are ultimately faulty, since they both came from different backgrounds, were of different age groups, and used their “madness” in very different ways in their comedy.

Perhaps the best footage of Jonathan cracking up Robin, and then the two trading odd improvs, is this outtake from a 1986 60 Minutes interview. Also wonderful is this goofy little sketch from Winters' 1986 cable special On the Ledge:

And the duo appeared on The

Tonight Show back in 1991, with Jon reminding Robin of their time

working on Mork and Mindy together: “You had access to more

medication in those days....” It is indeed a lovely thing hearing Robin laugh

at his hero.

No comments:

Post a Comment