[Note: This piece was written in early January, but

it wound up taking a back seat to my ongoing tribute to David Bowie. I herewith

present it because I remain stunned by the sheer terror some people have for

“spoilers.”]

When I first started getting seriously into film, my film teacher (who said many wise things) reacted to my asking him if it was "okay" to tell him about the plot of a movie he hadn't seen by saying, "it shouldn't matter if you know the end of the movie... it's how the director gets there that counts." I've heard his voice in my head for the past two decades each time I've seen/read/heard the Internet-spawned phrase "no spoilers!" Cautions about spoilers now even appear in essays in Criterion Collection booklets, where one *should* be able to safely assume the reader knows the end of the film they've paid for and are now reading an essay about — or do people read critical essays in DVD sets before they watch the classic films on the discs these days?

The fear that reading/hearing “spoilers” will ultimately ruin one’s experience of a film, TV show, or book (you rarely hear people complaining about books these days — more’s the pity) is, I believe intimately connected with the “trigger warning” idea that exists today. There always have been people who felt compelled to discuss plot details with people who haven’t seen the work, and there have always been people who wanted to exist in a bubble of innocence before they watched or read something.

Today, though, because of technology, the spoiler-shy individual can go around social media pleading with acquaintances not to “blow” a plot twist. Recently there was even talk of a filter that would block out any Web content that mentioned any item a person didn’t want “spoiled.”

When I first started getting seriously into film, my film teacher (who said many wise things) reacted to my asking him if it was "okay" to tell him about the plot of a movie he hadn't seen by saying, "it shouldn't matter if you know the end of the movie... it's how the director gets there that counts." I've heard his voice in my head for the past two decades each time I've seen/read/heard the Internet-spawned phrase "no spoilers!" Cautions about spoilers now even appear in essays in Criterion Collection booklets, where one *should* be able to safely assume the reader knows the end of the film they've paid for and are now reading an essay about — or do people read critical essays in DVD sets before they watch the classic films on the discs these days?

The fear that reading/hearing “spoilers” will ultimately ruin one’s experience of a film, TV show, or book (you rarely hear people complaining about books these days — more’s the pity) is, I believe intimately connected with the “trigger warning” idea that exists today. There always have been people who felt compelled to discuss plot details with people who haven’t seen the work, and there have always been people who wanted to exist in a bubble of innocence before they watched or read something.

Today, though, because of technology, the spoiler-shy individual can go around social media pleading with acquaintances not to “blow” a plot twist. Recently there was even talk of a filter that would block out any Web content that mentioned any item a person didn’t want “spoiled.”

There is an incredibly childlike aspect to the issue of spoilers. It’s as if the person avoiding them is a kid, not wanting to know that Santa and the Easter Bunny aren’t real. The more the person protests against spoilers, the more I have to wonder — is it really going to make that much difference in your life if you find out a plot twist, even a “major” one? (Almost invariably this twist involves the “surprising” death of a character.)

I spent three years editing a reference work (The Motion Picture Guide Annual) that provided

the full plots of the movies reviewed; the esteemed British magazines The

Monthly Film Bulletin and now Sight and Sound have provided

full write-ups on movies that include the finales of the films discussed. It's

a practice that serious movie buffs can deal with — the one genre I'd make an

exception for would be whodunit murder mysteries, which are pretty much

entirely predicated on their conclusion, so if you know the finale in those

instances you have lost some of the goofy charm of the genre (I'd throw

"twist" items like Homicidal and The

Crying Game in there). With most of the filmmakers I deeply love,

though, you can't ruin their films by telling me the end. A Godard film is like

a poem — whoever had a poem ruined by knowing the last line?

The spoiler phenomenon applies entirely to the storytelling aspect of cinema. With TV, that winds up being the central aspect of a program — since the fervent cries that “modern dramatic TV is the new cinema!” and “…is better than literature!” are both incredibly wrong. Cinema and literature are about content *and* form, whereas 98% of television, including the hands-down best-written and acted shows of the last 20 years, pay no attention to form, they are simply concerned with storytelling. Many viewers in turn confuse superb production design with a program being “cinematic.”

These shows are in fact exceptionally good TV, not cinema or literature — is it not enough for something to be exceptionally good TV? (I’ve always felt that the cinema/lit references indicate that the speaker doesn’t feel television deserves admittance into the Pantheon of important media.) Truly radical and superior television would encompass the few shows that toyed with the medium itself (Ernie Kovacs’ video comedy, The Prisoner, Dennis Potter’s teleplays). Although you will rarely hear those who holler “no spoilers!!!” being disturbed by knowing ahead of time that a program will be playing with their senses.

The spoiler phenomenon applies entirely to the storytelling aspect of cinema. With TV, that winds up being the central aspect of a program — since the fervent cries that “modern dramatic TV is the new cinema!” and “…is better than literature!” are both incredibly wrong. Cinema and literature are about content *and* form, whereas 98% of television, including the hands-down best-written and acted shows of the last 20 years, pay no attention to form, they are simply concerned with storytelling. Many viewers in turn confuse superb production design with a program being “cinematic.”

These shows are in fact exceptionally good TV, not cinema or literature — is it not enough for something to be exceptionally good TV? (I’ve always felt that the cinema/lit references indicate that the speaker doesn’t feel television deserves admittance into the Pantheon of important media.) Truly radical and superior television would encompass the few shows that toyed with the medium itself (Ernie Kovacs’ video comedy, The Prisoner, Dennis Potter’s teleplays). Although you will rarely hear those who holler “no spoilers!!!” being disturbed by knowing ahead of time that a program will be playing with their senses.

So what occasioned this meditation on the “don’t tell me

ANYTHING — you’ll ruin it for me!” panic-culture that proliferates on the Net?

Why, the fervor (now past —but it will recur) over the latest Star

Wars blockbuster, of course. My reaction to the SW

series is apathy bordering on narcolepsy. I saw the first as a kid and enjoyed

it, to a point (the point where I still preferred Star Trek

and knew that Lucas was playing with characters and situations from

Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers).

The deeply beloved second film I saw in a theater and thought was okay. I saw most of the third movie on TV and have never gone near the prequels (an extraordinary act of indulgence by the formerly talented gent who gave us THX-1138 and American Graffiti, and then never, EVER felt the need to make another non-benign film for adults).

The deeply beloved second film I saw in a theater and thought was okay. I saw most of the third movie on TV and have never gone near the prequels (an extraordinary act of indulgence by the formerly talented gent who gave us THX-1138 and American Graffiti, and then never, EVER felt the need to make another non-benign film for adults).

So I had zero interest in The Force

Awakens but knew that it would be overhyped to the max, and it was.

The “no spoilers!!!” fever pitch fascinated me, though. Consider this: the one

(and only?) *really* big revelation in the initial trilogy was one that was

hoary and hackneyed by Dickens’ time. (“I’m your father! Oh, and by the way,

the only important female character in this thing — she’s your sister!!!”)

What exactly could a “spoiler” be in the context of that kind of pedestrian, unimaginative (and downright irritating) mindset? Would someone important die? (Given the advanced of age of half-asleep action hero Harrison Ford, that’s not an unlikely scenario.) Would someone be revealed to be someone else’s aunt? Would one of the cutesy robots or Muppets or hairy sidekicks attempt a dry hump on another? Would the ghost of a talented sci-fi writer materialize to kill off the whole wretched series? Would one of the kids dressed in their cosplay finery puke up his popcorn in your local multiplex? Whatever happens, it surely won’t be original or innovative, or anything other than a sly move dreamt up to resurrect this moribund series of kiddie fantasies, of which so many adults have fond adolescent memories.

I hope that no one reading this blog entry had their experience of the SW movie ruined by an Internet reviewer, commenter, or troll who gave away the super-secret plot twist that I’m sure was super-fantastic. If that happened to you, may I suggest one of two things:

1.) Seriously consider avoiding further disappointments and life-ruining traumas by starting to attend (in a theater) films made by true artists. I guarantee that you will NOT be able to predict what’s going to happen next in a film by Godard, Greenaway, Maddin, Lynch, Herzog, Von Trier, or Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

2.) Aim to only watch the genres that the abovementioned Werner H. — who likes to make anti-arthouse cinema proclamations, even though his own work fits snugly into that category — has earmarked as “ ‘essential’ films: kung fu, Fred Astaire, porno. Movie movies, so to speak.” (Further thoughts from Werrner: “I love this kind of cinema. It does not have the falseness and phoniness of films that try so hard to pass on a heavy idea to the audience or have the fake emotions of Hollywood films.” Herzog on Herzog, p. 138). In this way you’ll never have your life ruined by finding out a spoiler.

What exactly could a “spoiler” be in the context of that kind of pedestrian, unimaginative (and downright irritating) mindset? Would someone important die? (Given the advanced of age of half-asleep action hero Harrison Ford, that’s not an unlikely scenario.) Would someone be revealed to be someone else’s aunt? Would one of the cutesy robots or Muppets or hairy sidekicks attempt a dry hump on another? Would the ghost of a talented sci-fi writer materialize to kill off the whole wretched series? Would one of the kids dressed in their cosplay finery puke up his popcorn in your local multiplex? Whatever happens, it surely won’t be original or innovative, or anything other than a sly move dreamt up to resurrect this moribund series of kiddie fantasies, of which so many adults have fond adolescent memories.

I hope that no one reading this blog entry had their experience of the SW movie ruined by an Internet reviewer, commenter, or troll who gave away the super-secret plot twist that I’m sure was super-fantastic. If that happened to you, may I suggest one of two things:

1.) Seriously consider avoiding further disappointments and life-ruining traumas by starting to attend (in a theater) films made by true artists. I guarantee that you will NOT be able to predict what’s going to happen next in a film by Godard, Greenaway, Maddin, Lynch, Herzog, Von Trier, or Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

2.) Aim to only watch the genres that the abovementioned Werner H. — who likes to make anti-arthouse cinema proclamations, even though his own work fits snugly into that category — has earmarked as “ ‘essential’ films: kung fu, Fred Astaire, porno. Movie movies, so to speak.” (Further thoughts from Werrner: “I love this kind of cinema. It does not have the falseness and phoniness of films that try so hard to pass on a heavy idea to the audience or have the fake emotions of Hollywood films.” Herzog on Herzog, p. 138). In this way you’ll never have your life ruined by finding out a spoiler.

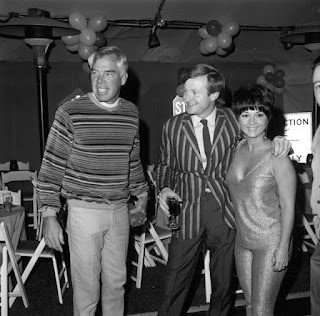

| |

| Has Werner Herzog seen many Russ Meyer movies? (The two sit here on a panel at a film festival.) |

To put it plainly, life is too short to be terrified that you’re going to find out that some ridiculously lame, poorly sketched character in a half-baked space opera is gonna kick off (or be brought back, or turn out to be someone’s son/father/uncle/pet ferret). Sit back, calm down, and enjoy some truly entertaining formulaic entertainment. Disney, J.J. Abrams, and other corporate forces behind the SW franchise will do just fine without your 15–20 bucks.