|

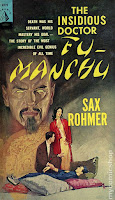

| The first novel (paperback reprint, U.S., 1961). |

He was a literary (well, hardback original)/mass-market paperback staple (much copied in the pulps and comics) and the subject of several feature films, and a landmark villain in 20th-century fiction. He is Dr. Fu Manchu.

The evil doctor is also a racial stereotype who was one of the stranger, more elaborate colonialist nightmares. An Anglo vision of a non-existent “Yellow Peril” that is very much out of step with the current century. And yes, his adventures — the better ones (and many of the movies are quite dreadful) — are still engrossing because he was conceived of as a master villain and, as every fan of genre fiction, genre movies, and comic books knows, a complex villain is always more interesting than a virtuous hero.

In this piece I will explore the different big-screen

incarnations of Dr. Fu as well as his appearances in other media. This binge

wasn’t occasioned by anything specific, except for the need to move beyond Bond

villains and Marvel bad guys, and return to the real McCoy, the supervillain

who provided the template that was later dutifully copied by Ian Fleming and

the Bond screenwriters, and Stan Lee and his bullpen of scribes (and

artist-cocreators like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko).

|

| The most-used photo of Fu's creator. |

"It's a blood and thunder aspect. He's not very good at characterization, and tends to make up for that with lots of incident and color and strange ways of speaking. He overwrites like mad. They're not detective stories — there's no puzzle element, because I don't think Sax Rohmer was subtle enough for that, but he really lays on the formula.

"And the formula is usually: eminent person is kidnapped in the first chapter, usually an archeologist... 'the man who knew too much." Dr. Petrie and Smith go on the hunt, it leads them to an opium den, they bump into Fu-Manchu or one of his agents. There's an elaborate machine of torture, which is seldom used but is described in a great deal of detail...

"...Like the penny dreadful concept of 'with one bound he was free' — there's no explanation, Fu comes back [from the dead with each new adventure]. So, they're fairly formulaic. But it's exoticism, the color, and this wonderful quality of prosaic, everyday London settings with this mad, exotic Oriental stuff going on just behind the scenes. I think that's the key quality to Sax Rohmer.

"I wouldn't make any claims for it as literature. But it's almost dreamlike. It's certainly magnified and has a kind of music hall, pantomime quality, particularly the early books."

|

| The third novel (aka" The Hand of Fu-Manchu," 1917). |

The connection Rohmer’s universe had to that of Sherlock Holmes’ creator is ridiculously apparent, especially when one reads the novels. The first few books in the series in the series of 13 novels (written over a half-century, from 1913 to 1959) are narrated by Dr. Petrie, who recounts his adventures with Sir Denis Nayland Smith, a very smart police detective who is able to deduce things from very little evidence and is perpetually ready to run to a certain location to foil the plans of the evil Dr. Fu-Manchu (who lost the hyphen in his name by the third novel, The Hand of Fu Manchu). Holmes and Watson they aren’t — Nayland Smith isn’t *that* brilliant, and Petrie is so madly in love (and lust) with Fu’s Arabic slave girl Kâramanèh that he can barely keep his mind clear to aid his friend.

And the criminal mastermind Fu, although having been clearly constructed from elements cobbled from Asian villains that came before him (an excellent essay on that can be found here) is clearly a new-model Moriarty, constructed with a Yellow Peril agenda. Rohmer’s most significant realization, though, was clearly that there were millions of readers who would follow a supervillain from book to book as easily as a super-detective.

Rohmer’s influence on Ian Fleming’s work is even more clear cut. And for those who’d like to hear it from the horse’s mouth, here is a quote from an interview that Fleming conducted with the inimitable (and clearly very drunk) Raymond Chandler, in which Fleming says he grew up reading the FM novels. This follows a question from Chandler about why he included torture scenes in all of his books:

“Really? I suppose I was brought up on Dr Fu Manchu and thrillers of that kind and somehow always, even in Bull-dog Drummond and so on, the hero at the end gets in the grips of the villain and he suffers, either he’s drugged or something happens to him . . .”

Fleming’s most explicit tribute to Rohmer is, of course, Doctor No, the Bond novel in which the secret service agent fights an Asian supercrook. But Fu is present in all of Fleming’s supervillains — he is in Le Chiffre, Goldfinger, Largo, Blofeld, Hugo Drax (played by Michael Lonsdale), and Scaramanga (incarnated by Christopher Lee, who later played Fu Manchu).

Bond’s creator clearly enjoyed Rohmer but felt that (post-Spillane) the sex and violence quotient had to be amped up. And so Bond is a dirty fighter constantly sleeping with different women, and perennially pursuing another eccentric supervillain (who quite often will abduct and torture him in some unusual way).

As with Fleming, Rohmer’s books have always been shelved in the Mystery section of bookstores and libraries, but their work has a lot more in common with action fiction from the pulps than the staid and quite intelligently plotted works of Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, or even (the creator of an equally popular Asian stereotype, Charlie Chan) Earl Derr Biggers.

The reason to revisit the world of Fu Manchu is not to wallow in the racism of the books, but to behold the supervillain that started off the craze that continues to this day. Nayland Smith describes him this way in a quote from the first book, The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1913; retitled The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu in the U.S.), that is used in most every article ever written about the character:

"Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government — which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man."

|

| The first edition of the first novel, 1913. (U.K.) |

Despite the racist stereotyping, Rohmer’s books remain eminently readable because of the pulpy quality of his work and for the sheer audacity of the melodrama:

“Of all the pictures which remain in my memory, some of them dark enough, I can find none more horrible than that which now confronted me in the dim candle-light. Burke lay crosswise on the bed, his head thrown back and sagging; one rigid hand he held in the air, and with the other grasped the hairy forearm which I had severed with the ax; for, in a death-grip, the dead fingers were still fastened, vise-like, at his throat.

“His face was nearly black, and his eyes projected from their sockets horribly. Mastering my repugnance, I seized the hideous piece of bleeding anatomy and strove to release it. It defied all my efforts; in death it was as implacable as in life. I took a knife from my pocket, and, tendon by tendon, cut away that uncanny grip from Burke's throat . . .

“But my labor was in vain. Burke was dead!” (The Return of Dr. Fu-Manchu, aka “The Devil Doctor,” by Sax Rohmer, 1916)

|

| The second novel, U.S. first edition. (1916) |

The way the racism is manifested specifically in the books is in the frequent hyperbolic mentions of the “yellow”-ness of the Asian characters’ skin and their sheer animal violence. Nayland Smith and Petrie are model British gentlemen, and so they often go straight for the throat by describing the “yellow” peoples as inhuman. (Although it should also be noted that Arabic races are very much a part of Fu’s squadron of evil sidekicks.)

The other side of this racism in both the books and movies is the overwrought obsession with Eurasian and Arabic women that the Anglo lead characters have. They are not simply attracted to these women — they are wholly and completely obsessed with them. In this regard Rohmer reflected the old world view that mixed-race exotic women were the biggest turn-on — and so Dr. Petrie never stops talking about Karamaneh, Fu Manchu’s slave girl, whom Petrie eventually marries.

One thing should be noted about Rohmer’s Brits — they are racist toward other groups as well. In Hand, two Jewish art appraisers come to look at a rare brass box Nayland Smith has obtained, and Petrie notes, “Lewison, whose flaxen hair and light blue eyes almost served to mask his Semitic origin, shrugged his shoulders in a fashion incongruous in one of his complexion, though characteristic in one of his name.” Also in the book another character is casually described as a “dago.” Thus, while Rohmer’s work and the better Fu films still function very well as purely thrilling entertainment, they do contain implicitly racist stereotypes (as does, it must be mentioned, much mainstream entertainment from the earlier part of the 20th century).

|

| The third novel, Sixties and Seventies U.S. paperbacks. |

And there is another, inverse factor in play here that most likely wasn’t intended by Rohmer (or was it?) — namely, that it’s fun to watch the Chinese supervillain toying with and torturing the hell out of the colonialist heroes. For, as much as the “codes” of action-adventure stories dictate that the audience is supposed to be sympathetic with the virtuous, it’s common that most viewers enjoy seeing the villain make mincemeat out of the hero.

The FM books and movies play with this notion — although Fu is “killed” at the end of some of the adventures, we know he will be back in the next installment, and Nayland Smith and his colleagues will be just as powerless to defeat him then. But in the meantime, we’ve seen the Good Doctor concoct some mighty impressive hoops for them to leap through….

|

| The fifth novel, Sixties U.S paperback. |

At various points he allows Petrie to escape because he would prefer to capture him and have him as a confederate (or a slave-employee); at other points he strikes a quid-pro-quo bargain with Nayland Smith or Petrie (again, usually freeing them), and keeps his word admirably. Thus Fu Manchu registers as a thoroughly British, oddly colonialist creation — a villain who wants to conquer the world but who will never break his word and thus is a highly ethical sadist and criminal mastermind.

It is also stressed by Nayland Smith that Fu possesses the

single most developed mind that he has ever encountered. This is another reason

why it is particularly fun to see the British leads one-upped by a member of a

race they consider beneath them. Fu himself acknowledges his evil genius quite

often and looks forward to his inevitable triumph over the Brits — but he

doesn’t want to win too easy a victory. (This was transformed by Fleming into

the oft-commented-upon torturing of Bond, rather than strictly killing him to

begin with.)

Part 2 to come!

No comments:

Post a Comment